Note: This article addresses works from the current AAM exhibition "Legacy: The Emily Fisher Landau Collection," which was previously covered by Xpress writer Steph Guinan in her July 9 piece "Big Names, Little Town." After seeing the exhibition I felt the need to address one specific artist's presence and importance.

“Legacy: The Emily Fisher Landau Collection” is in its final weeks at the Asheville Art Museum. The show is packed with an all-star cast of modern and postmodern artists that span the gap from mid-1960s pop art to the concept-driven anti-art of the late 1990s and early 2000s. So if Warhol and word art are your thing, you’ll undoubtedly enjoy the show.

But the real fuss should be about three comparatively small, vertically stacked photographs. They’re on a wall by themselves, but dwarfed by the expansiveness of the neighboring works, which include neon-toned, large-scale paintings by the likes of Barbara Kruger and Keith Haring.

They seem out of place, yet they are of inordinate importance — not only to the art museum, but also the Asheville arts community. Those three pieces are by William Eggleston, a Memphis-born and based photographer (rather, photography demigod). And it’s these three works that every photographer, artist and art lover in and around the city limits should come to see.

Prior to “William Eggleston’s Guide,” the 1976 solo Museum of Modern Art exhibition that catapulted Eggleston to fame, color photography was more or less a fine-arts faux-pas. It was technology best left to vacationing dads, birthdays and family gatherings.

The show was the first-ever solo exhibition of color photography at a major museum. Until then, MoMA had only shown a handful of color photos, to little attention or fanfare. But the Eggleston exhibition opened that door. It made color photography acceptable, even coveted by the country’s most important arts institutions.

To put it one way, Eggleston is to color photography what Faulkner was to Southern fiction and the “stream of consciousness” writing style — a catalyst and beacon. He made it “OK.”

The Egglestons are roughly 16×20 inches each, a size that’s easily shown-up by the imposing size and name-dropped grandeur of the other works. But there’s no underscoring how important these three photos are for the museum and the arts scene at large. They offer us a chance to see and study work that has zeroed in on, with lethal accuracy, and captured the “sense of place.”

To possess this in a series of paintings, drawings or photographs is no easy task. It’s to capture the people and the landscape. To visually convey an ideology and emotions of the individual or a city at large. And most importantly, the time in which they live.

In her essay for Eggleston’s 1989 book The Democratic Forest, author Eudora Welty calls it the “galvanic present” — the isolated moment that simultaneously embodies the past within the present’s forward motion. “These photographs all have to do with the quality of our lives in the ongoing world,” she writes. “They succeed in showing us the grain of the present, like the cross-section of a tree.”

Time is a delicate matter to impress upon a viewer. You get the sense that these photos are from the 1970s, but much like the cross-section of a tree, the view captured is one of the previous decades.

But to describe Eggleston’s works is an exercise in lyrical monotony. They’re in color, small in size and contain an array of everyday, mundane subjects. And they’re all “Untitled.” A 1976 New York Times exhibition review called them banal. But that’s just the point, they’re purposely banal.

Yet they’ve a visceral lure.

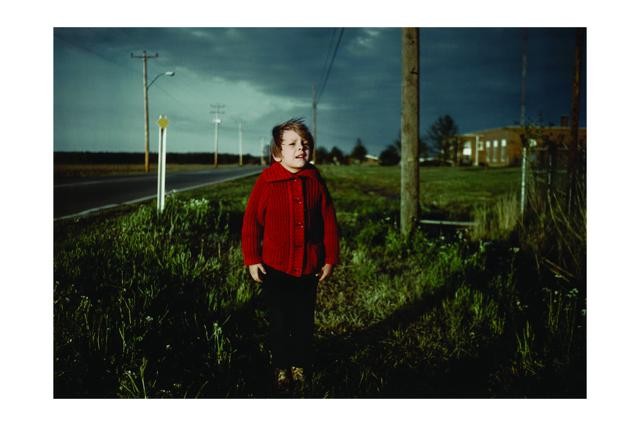

It’s the richness of their color, his attention to those everyday details and their off-kilter position. Each photo contains a sense of Eggleston’s reverence for the subjects, both animate and inanimate. It’s as if each photo is a celebration of something small, something that would otherwise go unrecognized. His subjects are all from the delta and the Deep South. In this case it’s a boy in a sweater, several dolls perched on a Cadillac hood and a rebel flag license plate stuck in a tree — all taken in the early 1970s. They’re odd, poised, uniquely Southern and wholly in and of their time.

The boy is wearing a fire-engine-red sweater that swallows his torso. It looks brand new and uncomfortably woolen, a feeling evident in the way he’s craning his neck to escape a never-ending itch. The background is flat and eerily devoid of life, save a highway and a brick building tucked in the right corner. It has the appearance of a school, which makes this photograph seem even more post-Christmas when you add the sweater.

In “Untitled: (Baby Doll Cadillac)” a dozen dolls are positioned on the hood of a baby-blue Cadillac. Most of them are waving. The central figure is straddling the hood ornament. The photo’s got a jockey-lot or roadside element to it, as if the dolls are perched and positioned for sale.

And while parallels could be made to his image of a rebel flag license plate thrown into a bush and the post-Civil Rights Act fall of Dixie, it’s more likely Eggleston’s keen eye looking at the plate’s blood red hue, rust and a bullet hole.

You don’t have to travel to the Delta to understand the works. Think of these three images as snapshots from a greater regional view. An essence — the barren landscape, the poverty and the ordinary. Captured almost too well even. If you’ve ever been to Memphis and backwoods Mississippi, you may agree: Eggleston’s photos are far more exciting than the real thing.

“Legacy: The Emily Fisher Landau Collection” is on view at the Asheville Art Museum through Sunday, Sept. 8. For more information visit www.ashevilleart.org.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.