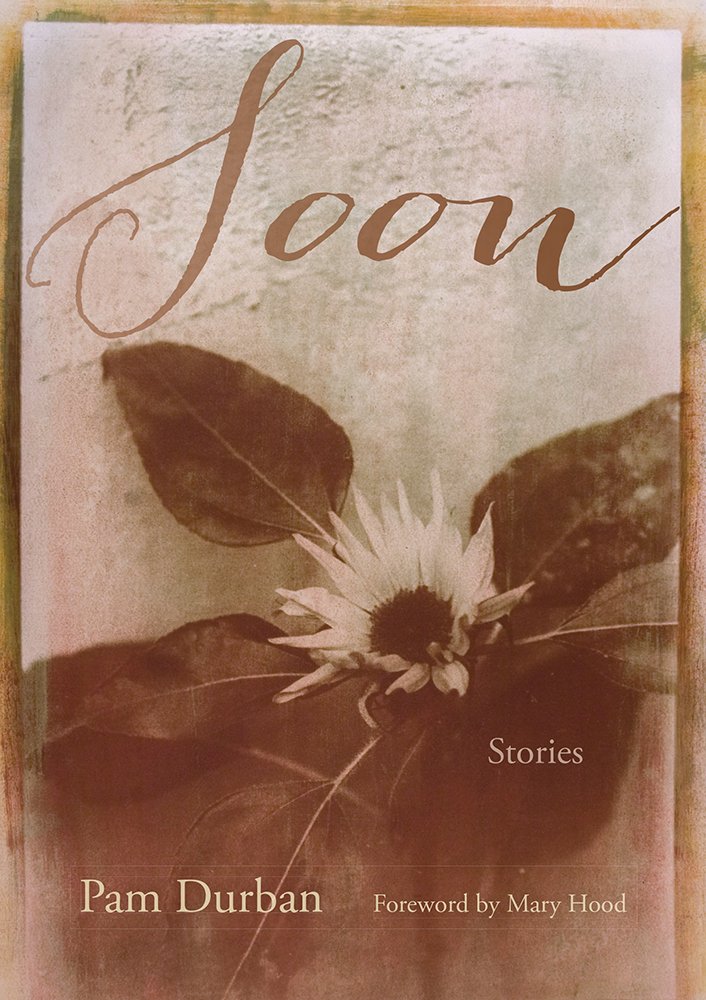

Award-winning author Pam Durban will present her new short story collection, Soon at Malaprop’s on Monday, Aug. 24, at 7 p.m. The title story was selected by John Updike for Best American Short Stories of the Century.

Q+A from Durban’s publicity team:

How did this terrific collection of short stories come to be published by Story River Books?

Pam Durban: USC Press was interested in re-issuing two of my books in their Southern Revivals series, and sometime during that discussion, I mentioned that I had about a dozen short stories that I thought would read well as a collection. Jonathan Haupt, the editor of USC Press, was interested and so was Pat Conroy, the editor-at-large of Story River Books, and the book of stories went through their review process and was accepted. I feel very lucky to have landed in such a welcoming place. As Jonathan Haupt told me, they’re committed to their books for the long haul, and I’m happy to be published by a press that values and supports serious writing.What was it like to have your story “Soon” published in the Best American Short Stories of the Century?

It was a big surprise and a huge honor, of course, and also a little overwhelming, to have my story included with stories by Katherine Anne Porter, Hemingway, Willa Cather, Alice Munro, Eudora Welty and Raymond Carver.When the book came out, the publisher flew us to New York for a party. There was a gigantic pyramid of books in the middle of the floor of the restaurant where the party was being held, and John Updike, who’d chosen the stories for the anthology, made it a point to talk to every writer there in a very generous and specific way about what he saw in their story.

What if your yardstick for measuring a great short story—for yourself and other writers and your students at UNC?

A great short story, like all art, gives me a new way to see the world. Another way of saying this is that a great story discovers something, and when I read a great story I feel a mind and heart at work on some important human question. In Arthur Miller’s words, it brings “news,” and that news is always about who people are and why they do what they do.I try to find and deliver that news in my stories, and over time, I’ve discovered what someone has called my “required subject matter,” meaning subjects I’m never finished with, that I keep coming back to for another look. This required subject matter shows up in the stories in SOON. In “The Jap Room” and “Island” it’s war. It’s Southern history in “Rowing to Darien” and “Gravity.” In the title story, “Soon,” it’s the unending sense of possibility that keeps us groping forward through life. And I think it’s love and letting go in “Forward, Elsewhere, Out” and “Three Little Love Stories.”

Which magazines do you most respect for their publishing of short stories?

Literary quarterlies are the magazines I know best. My favorites are the magazines with the longest histories of publishing lively, high quality work, so my short list would be The Southern Review, Tin House, The Kenyon Review, The Georgia Review, Shenandoah, The Paris Review. And I’d include the Atlanta-based Five Points in this list as well. I was privileged to serve as a founding co-editor of the magazine as well as the fiction editor for the first five years of its existence. The magazine is still going strong 16 years later. I just got the most recent issue and I was pleased to see a moving tribute to the late Philip Levine, who was a friend and supporter of the magazine from the beginning.What is your writing process? How has it changed over time?

I envy my writer friends who can compose on the computer, but I have to write by hand. For me, it’s always been the eye, hand, pen, paper connection that starts words flowing. Writing by hand also creates big, messy, manuscripts because as I move forward through a piece of writing, I also go back and layer in more pages, and trying to sort out those layers when it’s time to type it up can be maddening.I believe in taking time and taking care, and I can’t let a story go until I’ve discovered something that I didn’t know when I started writing it, so I revise a lot. It might take me 300 pages of drafts to chase down a 20-page story. Very often, if I’m stuck, I cut a story into pieces and lay those pieces out on my dining room table and move things around. This is probably the most exciting part of the revision process for me because it unlocks a story and keeps it in motion.

How much of a role does an editor play in your revision process?

It varies, but I’ve had a couple of crucial editing experiences. One was with the late Stan Lindberg, the long-time editor of The Georgia Review, who first published one of my stories. He was an insightful editor and a very kind man, and he edited with a light but decisive touch that really helped me fix what needed to be fixed in my story without losing heart.The other was working with Michael Griffith, twice. He was the fiction editor at The Southern Review who accepted “Soon” for publication, and he took every word seriously and wanted to make it exactly the right word. He was also the editor for LSU Press’s “Yellow Shoe Fiction” series, which published my novel The Tree of Forgetfulness. In the process of editing that book, he called me out, Southerner to Southerner, about a moment of racial reconciliation toward the end of the book that didn’t ring true. He’s the gold standard of good editing for m, and I wrote a more honest book because of him.

As a South Carolinian living now in North Carolina, what are your impressions of events following the murders at Emmanuel AME, and the removal of the confederate flag?

I was sickened and appalled by the murders, but I also think this tragedy has raised issues about the past that we white South Carolinians need to look at it without retreating into sentimentality or defiance, and I hope and believe we can honor the dead by doing that. As the historian John Hope Franklin said, “We have to confront history. We have to face it down to be certain it won’t haunt us again.” As I see it, a confrontation with South Carolina’s past would involve seeing the continuity of our history and reminding ourselves that the tragedy at Emmanuel AME was not an isolated incident perpetrated by an outlier, but that Dylann Roof is the latest actor in a long history of white supremacist violence that runs from slavery through Reconstruction and the Jim Crow era, and produced people like “Pitchfork” Ben Tillman, who declared that South Carolina blacks must submit to white rule or be exterminated.My own moments of reckoning have come from writing my last two novels, So Far Back, which is about slavery in Charleston, and The Tree of Forgetfulness, about a 1926 triple murder of three members of the Lowman family in Aiken, S.C., my hometown. In researching and writing those books, I felt the weight of history descend, and the need to educate myself in ways that I hadn’t been educated growing up. The research for both books took me to archives around the state. For So Far Back, I read newspapers and diaries and records from the Workhouse in Charleston. I read plantation ledgers and letters and sermons preached to Negroes. For The Tree of Forgetfulness, I read coroner’s reports and newspaper stories, NAACP documents and transcripts of interviews. I came away from that research troubled by what I found, but hopeful that the truth of history can be recovered and acknowledged and that that accounting might lead to healing.

I was proud of my home state for taking down the Confederate flag, and I hope we can continue to work on the healing project that lowering the flag might have started: Truth first, then reconciliation.

What was the pivotal event and then the path that led you to become a writer?

I think I came to writing through a process of elimination. In my 20s, I had a series of writing jobs. I worked on a small newspaper in upstate South Carolina, and on a couple of alternative newspapers in Atlanta. But in every case, there came a time when I wasn’t satisfied with the writing I was doing because it wasn’t mine in the way I wanted it to be, and I’d get restless and move on.If there was a defining time, it was the year or so that I worked at a community service organization in an old textile mill village in Atlanta called Cabbagetown, where I compiled and published a series of interviews with some of the oldest women in the community.

That project was so important to me because that’s where I first began to see what a story was and what it could do. The stories in that book weren’t fiction, but I learned some good lessons from them about fiction writing. I learned that in an immediate, almost tactile way, a story is an experience, that it has the power to bring a whole world to life.

After that project, I went to the Iowa Writer’s Workshop and then on to a series of teaching jobs that kept me living outside the South for the next 10 years. Those 10 years were crucial to my writing because they gave me a different perspective on the South and when I came back, I could see it as an outsider and an insider. It was that kind of double vision that I think made it possible for me to write the two novels I’ve mentioned as well as my stories about the South.

What’s next?

A memoir about how my father’s military service shaped our family life. A long piece of fiction, maybe a novella, about an obese woman’s bid for love and happiness. And a short story about a young woman who works in a massage parlor near the Gettysburg battlefield.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.