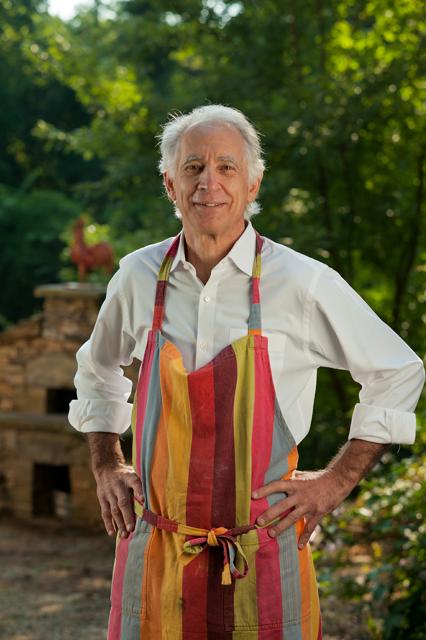

- Every rose has its thorn: Mark Rosenstein in his garden. “Most people could not do what I do.” Photo by Warner Photography

- Pig business: Chad Gibson manages the south Asheville 12 Bones. Photos by Max Cooper

- Passion pit: The restaurant business is a hot and dirty labor of love, says Jason Roy.

- Chef talk: “People in the industry, we do it because we love it," says E.B., a line cook at Chai Pani.

- Looking glass: Natalie Byrnes and Eddie Hannibal just opened the Glass Onion in Weaverville after moving from the Hamptons. They like the tight-knit sense of community here, they say.

Through the past few decades, the public perception of chefs has shifted. Once a strictly back-of-the-house position, chefs are now considered rock stars in aprons shouting at underlings, and globe-trotting gourmands eating strange foods and hamming it up for the camera. Thank you, Food Network.

The rise of the celebrity chef has spawned a slew of hopefuls who have rushed to enroll in culinary school (where tuition can run upward of $30,000 a year). Suddenly everyone wants to be a chef. Who wouldn't want to be a knife-wielding celebrity who makes more appearances on the red carpet than in the kitchen?

Real workaday chefs have a tough job to do — and most have to peel a lot of potatoes before they even get close to chef status, culinary degree or no. And even those who succeed have many cautionary tales.

Considering getting into the business? You need plenty of crazy. Read on.

The hot seat

Chad Gibson, kitchen manager of 12 Bones in Arden and former recruiter for Johnson & Wales, has met plenty of people who think that they'd get a kick out of cooking professionally. "It's a romantic ideal: 'I love to cook, it's my passion, I can make a living of it,'" he says. But here's the hard truth: "It doesn't matter where you go to school, you're looking at anywhere from two to 10 years hard labor before you'll be the chef,” he says. “There's no way around it."

It doesn't matter how much money you pour into a fancy culinary degree, being in a kitchen is simply hard work. "It's a physical job and a mentally stressful job," says Gibson. "Then you throw into that mix the realities of interpersonal communication and customer service — it's difficult."

Elizabeth Bass (or E.B.), a line cook at Chai Pani who has worked in many other restaurants, agrees. "It's not puppy dogs and hearts and unicorns. It's hard work. And it's not a bunch of kids in white coats standing around talking about French cooking, either." Professional cooking entails a lot of rapid-fire production and massive amounts of prep work and cleanup.

Still, the world of the professional chef has become marketable and hip, especially with the explosion of the "foodie" scene. The people who think it would be a trip to stage at a famous restaurant don't seem know the whole story — or how hot and dirty it can really be, she says. "Standing on your feet for 10 hours chopping is not fun. But people in the industry, we do it because we love it," she says.

But don't call her a chef. "I'm a line cook,” she says. “I'm a dirty cook. That's just what I am. And I really enjoy what I do. And sometimes I hate what I do. It gives and it takes. And I really want people to appreciate the people in this industry … A lot of service industry workers, both back and front of the house, keep this town afloat."

Boneyard

"There's two people in the culinary industry," says Gibson. "Those that love it, who are professionals, motivated to do it, and do it really because they couldn't do anything else. It's their life and their passion and they're professionals. … And there's also a lot of shitheads in this industry. As a chef, it's hard to get a lot out of a clock-puncher."

Gibson has to hire dedicated workers at 12 Bones. Only dedicated workers could handle the crushing heat and the insane pace that's required to keep up with the volume of customers the restaurant has to accommodate.

So far, the record for total number of people served in a 5-hour span at the Riverside location is 852. "It's the epitome of turn-and-burn. It's production cooking," says Gibson. Regardless, everything at 12 Bones is made with care and an eye to detail, Gibson says — it's what attracted him to work there in the first place.

But feeding that many faces takes major preparation. That's why, even though the restaurant is only open for weekday lunches, there's almost always someone prepping for the next push. (12 Bones is not yet a 24/7 affair, says Gibson, but at 18/6, it’s pretty close).

"People give us a hard time about our hours all of the time. But barbecue is a business of low and slow, and the thing that makes 12 Bones good is that we buy wholesome, whole foods and, from scratch, we turn it into something great. The amount of time required is insane. I have items that take 13 hours to cook." In five hours, says Gibson, he can easily sell it all. "We've got that production down to a science. But we're unwilling to compromise on quality and unwilling to ask too much of our employees because happy people make delicious food."

Still, happy or not, the pay for most kitchen positions kind of sucks (which is part of the reason why Gibson recommends that aspiring cooks get a "solid education, not an expensive one").

"The reason that the pay scale is so bad, the reason that the benefits are so bad and the reason that people are forced to work insane hours is because profit margins are so slim," he explains. "A good restaurateur, doing everything right, may cover three to six percent profit per year … The margins are razor-thin."

Balancing the budget

"Running a restaurant is the most inconsistent, unpredictable business that probably is out there," says Natalie Byrnes, a Johnson & Wales grad who owns the new Italian restaurant in Weaverville, the Glass Onion, with chef and husband Eddie Hannibal. Both Hannibal and Byrnes have decades of experience opening and running restaurants from Aspen to the Hamptons.

Keeping an eye on cash flow is a huge part of a chef's job. "Fifty percent," says Byrnes. "It's absolutely half of what you're doing, because the money is the most important part of it. The money dictates how you operate your kitchen … and how the menu is executed."

Food cost is a touchy subject in most restaurants. Many restaurateurs say that the sweet spot is somewhere around 30 percent of total operating cost (with labor eating up another 30). At the Glass Onion, the couple tries to source locally, offer top-notch meats and make everything by hand. But the best ingredients can mean either higher prices or smaller portions; sadly, diners, you just can't have it all.

With the average salary in the Asheville metro area hovering at $26,313, according to the Asheville Chamber of Commerce, the majority of customers value a low price point — and they make no bones about it. Even though the pasta is made fresh on the premises, for example, diners at the Glass Onion sometimes get sticker shock over the $15 cost of a dinner entree.

It's certainly a balancing act, the couple says. "There's only so much we're willing to sacrifice, in terms of quality," Byrnes says. "Then you become a mediocre restaurant with mediocre ingredients, and there's nothing special about that," Hannibal adds.

Location, location, location

Mark Rosenstein is familiar with the ups and downs of the industry. Rosenstein opened The Market Place on Wall Street in downtown Asheville in 1979, when the area was "dead" at best, he says. He lost money for the first three years, and friends and acquaintances were skeptical. What was the consensus? "Stupid location, stupid town, stupid concept," he says.

Rosenstein and staff also tried to make absolutely everything on the menu by hand, driving up labor cost. At that time, Rosenstein says, he had little choice. "We couldn't get anything to the standards we wanted, so we had to do it ourselves. Now you can get great chocolate, great bread, have meat fabricated the way you want," he says.

Running a kitchen costs more than money — it takes up a lot of time, too, which eats into the personal life of the chef. Until he retired from restaurant work, Rosenstein worked 14-hour days with a half-hour break for dinner. "It becomes your entire life," he says. "If you're a really good restaurateur and a really good cook, the client always comes first. … And, if someone's camping or they come in right at closing and sit there for 45 minutes before they order, you wait for them to do that. You have a family waiting at home, but what do you do? You sacrifice your family for the person sitting at the table."

Indeed, when Xpress asked celebrity chef Anthony Bourdain if it's possible to be a great chef and balance family life and work, Bourdain said no. "To be a … really top-flight, national-profile, respected as being at the top of your game [chef], somebody's going to pay the price there. Not just you, the people that love you, the people that count on you."

Balancing act

Jason Roy agrees with that. "It's been hard for me as a chef with a family," says Roy, the chef at the Lexington Avenue Brewery. Roy actually has it pretty lucky in that his wife is a culinary grad he met in a fine-dining restaurant. Being familiar with the industry, she knows how hard the hours can be — but having a son changes things.

That's why, three years into working at the LAB, Roy has whittled his work week from 100 to 45 hours (although it's taken 17 years of hard work and five executive chef gigs to get there). "If a restaurant's open 14 hours a day, seven days a week, you do the math. You pretty much need to be there all the time. Hundred-hour weeks are not abnormal," says Roy.

Roy thinks that, without his own level of dedication, his staff would not have followed suit. It's the staff, after all, that allows him to spend some nights and weekends at home. "You have to work hard to be successful as a chef," he says. "You have to show the people that work for you how the job is done. If you don't know how to work, you don't know how the job is done. You can't teach those people."

Despite the somewhat dream schedule he's got now, Roy hopes to open a restaurant some day. "I know, it's ridiculous," he says. "But the epitome of the restaurant that I want, in my utopian fantasy of what can happen in a restaurant, would be to [work] with my family. To be with my family and to be able to do what I love is the goal."

With the failure rate of restaurants so high, it's a risky endeavor. "I pride myself in the ability to make money for the people that I work for," Roy says. "I think I've got what it takes."

The art of work

The pay sucks, the hours are bad and it’s really, really hot. So why cook? After all, it’s not all “wine tastings and farm tours and book signings and creating new dishes,” says Gibson. “There are so many harsh realities to what it actually is. Can you make a nice living for yourself? Yes. But you’re probably not going to get rich.” But food, he says, is his life. That’s why his shelves are filled with cookbooks and his money goes to sampling the food in (sort of) faraway places (like Chicago). “It’s because it’s my passion,” he says.

That’s why Roy does it, too. Without passion, he says, there’s no point. “Don’t do it unless you love it, unless you’re meant for it, unless it’s calling you. You’ll fail and I will laugh at you in my kitchen. You’ve got to be a hardworking person that really loves it and understands it and is an alchemist.:

Rosenstein, who’s referred to his own style of cooking as “mountain alchemy,” can’t imagine having done anything else. Ask him how his life would have been different if he’d never been in the hospitality business, and he’s momentarily at a loss for words. “I’ve only thought about how to get away from it,” he laughs. “But life has been so rich and I have so many human connections and relationships on so many levels because of it.”

Lately, Rosenstein has eased back into selling food through catering, though he has one condition: “The client is going to have to respect our world. If you don’t respect our world, you can’t have what I do. It’s simple.”

When asked to elaborate, Rosenstein says this: “You’re forgiving of people that don’t quite understand what’s going on and what it takes to do what we do, how much we give of ourselves. Most people could not do what I do. I don’t care how many levels of education they have, most people could not deal with the complexity of running a restaurant. I’ve had people say, ‘Well, I could do this at home.’ I’ve learned to say, ‘No you can’t. This conversation is over. Nice to meet you.’”

— Send your food news and story ideas to food@mountainx.com.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.