Could a “superbug” bacteria outbreak in China threaten Western North Carolina sooner than you can say “zombie apocalypse”? It’s possible, since a deadly pathogen can make it around the globe in 24 hours or less, and in just eight hours, one E. coli bacterium can generate more than 16 million clones that make their host very, very sick — particularly if the mother strain is one of a growing number of antibiotic-resistant superbugs that have health leaders on alert from Asheville to Beijing.

“It’s a scary situation,” says Sid Thakur, a N.C. State University researcher and professor who works on the problem at “multiple levels,” from studying outbreaks across the world to helping farmers find safer ways to raise pigs in North Carolina. Bacteria have been evolving for millions of years — far longer than humans, says Thakur. “I’m not surprised when we see new antibiotic-resistant pathogens. That’s evolution.”

The list of strains resistant to antibiotics is longer than ever before, and it’s growing, he notes.

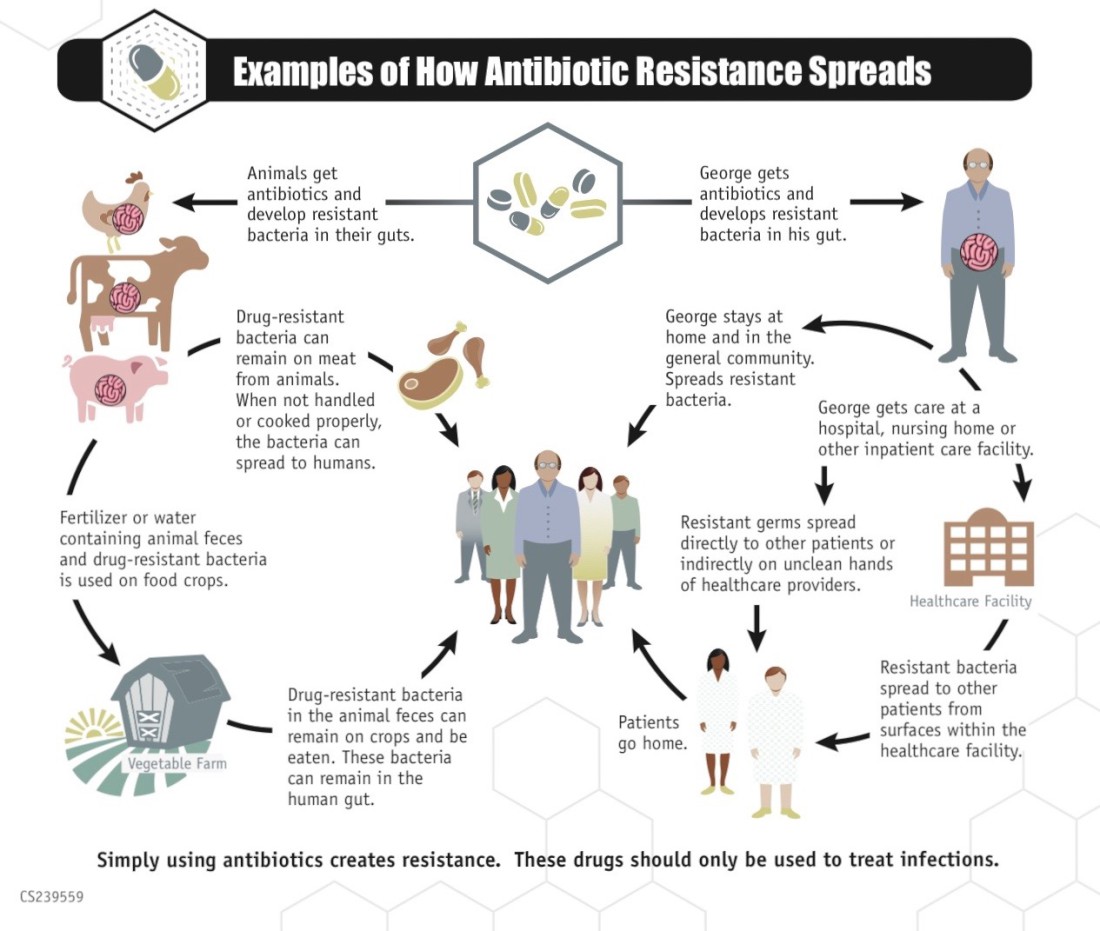

The situation has the World Health Organization on alert and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention pushing to educate medical professionals and the public, as well as significantly reduce the use of antibiotics in food animals. The CDC’s “Get Smart” campaign, for example, connects the rise of superbugs with the overuse and misuse of antibiotics, cautioning doctors and patients alike that taking the drugs for, say, a cold virus “can cause more harm than good, [increasing the] risk of getting an antibiotic-resistant infection later.”

“Viral [illnesses] are not treatable with antibiotics,” says Asheville physician Dr. Susan Bradt. But patients ask for them, and doctors — trained to help — have prescribed them, she says. In the nearly 100 years since the discovery of such lifesaving drugs as penicillin, American culture in particular “relies too heavily on that quick fix. We don’t allow ourselves to rest when we get sick, [and] antibiotics used to be handed out like candy.”

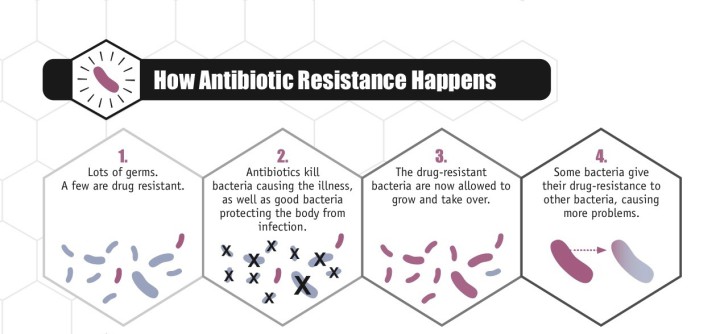

Bacteria have responded by rapidly adapting. Even before penicillin went from discovery to common use in the 1940s, resistant bacteria had evolved, spreading rapidly around the world.

“When you add an anti-microbial into the test tube, a lot of [bacteria] will die, but many will survive,” says Thakur, who injects humor into his talk about nucleotides and DNA transfer. “When you kill [the] competitors, the surviving bacteria say, ‘It’s our time to rise and shine.’ Pathogens are way smarter than us and way more adaptable.”

And bacteria outnumber us. They’re found in every environment on Earth, from the soil to Arctic snow to the cleanest human skin, says Thakur. Resistant salmonella strains even have been found in pigs that haven’t been treated with antibiotics. The use of antibiotics in food animals was banned in Europe in 2006 but is still used in the United States for spurring growth and preventing infections. But by the end of this year, the practice will be sharply curtailed in the U.S., one of several changes that make Thakur optimistic.

But he admits, “Sometimes I feel like, is this a battle we’re ever going to win?”

Good to bad

Most bacteria are beneficial, and even ones we think of as “bad” have harmless (or at least more treatable) cousins. There are about 10 times as many bacterial as human cells in our bodies, and most of them live in our guts as an integral part of our microbiome, says Bradt. “All of them live in harmony, [and] they’re the interface between the outside world and our inner bodies.”

She cites new research that explores bacteria’s role in our day-to-day health, from obesity to depression. Bradt also offers this anecdote from her own practice: A patient was treated with strong antibiotics for an infected cat scratch; the treatment weakened her good bacteria and led, over time, to an autoimmune disorder.

While acknowledging the necessity of the patient’s initial treatment, Bradt wonders about the consequences for humanity. “Are we dooming ourselves?” she asks.

“Kids who are treated more frequently with antibiotics are more likely to develop obesity as adults,” says Bradt, citing a variety of studies. As adults, those children might continue to have compromised immune systems, while bacteria develop more and more resistance.

Clostridium difficile, for instance, can exist harmlessly in the human gut until an antibiotic treatment kills off the bacteria that usually keep it in check, she continues. Potentially life-threatening, C. difficile causes severe diarrhea, and it can spread easily and rapidly in a community. In 2011, more than 200 deaths in North Carolina were linked to or caused by C-diff, according to a state report.

That puts the pathogen on the CDC’s top-three list of serious threats in the United States. It’s joined by Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, which includes E. coli, and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. So far, none of these have led to deaths in the WNC mountains, though the region’s largest hospital, Mission Health, reported nearly 127 C-diff cases in 2014, and CRE led to several fatalities in nearby Lincoln County in early 2015.

Nationwide, by the CDC’s most conservative estimate, more than 20 million Americans get sick with antibiotic-resistant pathogens, and more than 23,000 die each year.

But antibiotics save lives too, says Dr. Chris DeRienzo, Mission Health’s chief patient safety officer. “The benefits of using antibiotics outweigh the risks, but we’re coming to learn there’s always give and take as we treat illnesses,” he says.

Patients treated for pneumonia may become susceptible to C. difficile. Augmentin, which is commonly used for sinus infections, also upsets patients’ gut bacteria, he continues. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (aka MRSA) can often be treated with such antibiotics as Bactrim, but it’s “resistant to a broad class of drugs,” making it hard to treat, he explains.

In a notable local case in 2008, UNC Asheville basketball player Kenny George had to have one of his feet partially amputated due to a MRSA infection.

“When I think of the bugs that are scariest, I think of those for which we have just one or two antibiotics that work,” says DeRienzo. MRSA is one of those, which the CDC lists as a “serious” threat, one tier down from the top three. That second-tier list includes nearly a dozen pathogens, such as two salmonella strains and a drug-resistant form of tuberculosis. There’s been a recent outbreak of the latter in a small county in central Alabama.

By some estimates, deaths linked to antibiotic-resistant bacteria will outnumber cancer deaths by 2050, Thakur mentions. “This is one issue that’s staring us in the face.”

What’s a doctor to do? DeRienzo describes one of the medical profession’s most powerful antibiotics, Carbapenem, as a “cannon” that can annihilate many infections. It may be used initially, followed by antibiotics that, “like a fleet of archers,” more specifically attack an infection as doctors zero in on a pathogen’s weaknesses; or it might be the last resort.

“If Carbapenem isn’t effective, you’re down to very few choices, and that’s where it gets scary,” he says.

Come together

Many of the infections on the CDC’s urgent-threats list don’t have to be reported to state, federal or local agencies. That makes infection patterns hard to track across communities, regions, countries and the world. Bacteria, as Thakur notes, don’t respect political boundaries. “Why do we need to worry about what happens in China [or elsewhere in the world]? Because bacteria can make it here in 24 hours,” he muses.

In an E. coli outbreak in Europe, scientists were initially perplexed at how such a diverse group of patients had acquired it; they eventually figured out that the initial patients had all been to India recently, says Thakur.

“We need to talk about this topic on a global scale,” he says. “We’re going to have to work together.”

Consider this observation, made to medical leaders in 2014 by Dr. Zack Moore, an epidemiologist with the N.C. Division of Public Health: The “use of antibiotics by one person affects others in the community and makes it less likely that antibiotics will be effective in the future.”

DeRienzo, who collaborates with Moore as a fellow member of North Carolina’s Healthcare‐Associated Infections Advisory Group, agrees. “Our bodies are amazing at regulating themselves, but everything has a connection to everything else.”

Flu vaccinations can help prevent illnesses that lead to lung infections, which require antibiotic use that sets up an outbreak of C-diff. Simple hand-washing and other preventive measures can stop MRSA and other infections, notes Dr. Jennifer Mullendore, medical director for the Buncombe County Department of Health. Educating both doctors and patients about the appropriate use of antibiotics, as well as being more judicious about prescribing them, can help reduce the rise of superbugs, she continues.

“Antibiotic stewardship is a foundational part of trying to reduce healthcare-associated infections,” DeRienzo says. And it’s one of the keys to stemming the rise of antibiotic-resistant bacteria in all communities.

“We’re moving in the right direction, but we’re not where we need to be,” says Mullendore. She calls for better patient awareness, from understanding the difference between viruses and bacterial infections to finishing an antibiotic treatment and not sharing the drug.

As for the CDC’s top-three threats, she’s not aware of N. gonorrhoeae being reported in the region, but the infection “has become resistant to so many antibiotics.” The Health Department periodically gets calls from schools and sports organizations that want to learn about measures to prevent MRSA, she notes. “It would be great if we worked more on prevention,” Mullendore says.

But in addition to better education, she says, “We need new antibiotics.”

In the past decade, however, very few new medicines have been added to the medical arsenal against bad bacteria. Drug development is expensive and problematic, says Thakur. A pharmaceutical company can spend billions to develop a new antibiotic. “Then when one nucleotide changes in the pathogen, the drug becomes less effective,” he says.

All of these medical professionals also suggest that attitudes about antibiotics need to change. Thakur mentions Ph.D.-educated friends who get frustrated when a doctor doesn’t prescribe antibiotics for their children’s viral infections. Bradt, meanwhile, says we need to include more fermented foods in our diets and nurture our microbiome. And DeRienzo suggests that better data could help medical providers do better at targeting infections by establishing a community “biogram” — an analysis that charts how susceptible pathogens are to various drugs.

“Bacteria spread within communities,” he says. Hospitals often develop biograms for internal use, but a city- or countywide analysis could identify broader patterns and types of infections, thus helping medical professionals minimize antibiotic use and pick the best treatment, he explains.

Thakur, meanwhile, calls for a “one-health” approach. He cites the interactions and connections among humans, animals and the environment, recalling that, as a grad student, he worked with a farmer who raised his dozen pigs with as few antibiotics as possible. That farmer’s herd now numbers in the hundreds, demonstrating the demand for organically raised meat, says Thakur. And the underlying idea — a willingness to approach agriculture in a way that considers the interconnectedness of humans, animals and nature — “gives me some hope.”

DeRienzo, meanwhile, says he has a 100-year-old medical textbook that notes such antiquated treatments as [mercury and the arsenic-related drug Salvarsan] to cure syphilis. “Life before antibiotics — that would be scary,” he says.

But there’s no single fix for antibiotic-resistant bacteria, DeRienzo continues. “The more that folks read about [the problem], the more they understand, the clearer it will be, at the community level, how we can put together a number of initiatives that can make a difference.”

MORE INFO

“Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the U.S.,” the CDC’s 2013 report: avl.mx/25y.

“Get Smart” campaign: avl.mx/25z

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.