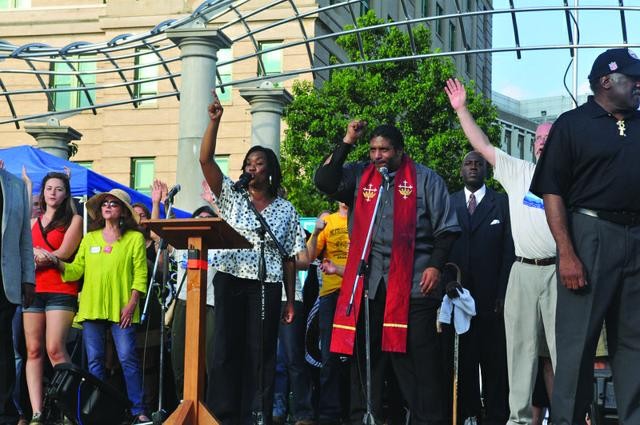

- “Forward together, not one step back!” — Rev. William Barber, Aug. 5 Mountain Moral Monday photo courtesy of the UCC Church

- “As we move closer to God, we should also be moving closer to people. And vice versa: as we move closer to people, we are actually moving closer to God.” — Rev. Amy Cantrell (pictured with Lauren White) photo courtesy of Amy Cantrell

- “In order for society to progress, the people have to be better educated…to have an education that looks to the interrelationship of all things and people.” — Sid Jordan, Prama Institute photo by

- “Part of my work as a being on this planet is to free people…from mental and spiritual slavery.” — Nia Yaa, Ra Sekhi Arts Temple photo by

- 'We are here with the Shogun workers, people of faith, and other members of the communtiy to remind everyone that this is not a border issue, these are our friends and families and people in our community.” — Rev. Lisa Bovee-Kemper

- Photo by Carrie Eidson

Spirituality can’t be confined to a meditation room, church or synagogue. It is inextricable from everyday action, and for many leaders and members of the local spiritual and faith community, the crux of spiritual experience comes in standing up for something larger than themselves.

“I am called to be an activist primarily because of my faith,” says Lisa Bovee-Kemper, Unitarian Universalist minister. That’s a sentiment shared by many Asheville-area faith leaders who discussed with Xpress their relationship with spirituality and activism.

We learned that these spiritual leaders are part of an emerging vanguard that’s reclaiming the moral domain and adding their own inspirational element to activism. Their work is galvanizing social- and environmental-justice movements in Western North Carolina and throughout the state.

Reclaiming the conversation

“I regret how much the religious discourse in our country sounds like a swimming pool, where all the noise is coming from the shallow end,” says Father Thomas Murphy, priest at All Souls Cathedral in Biltmore Village and steering-committee member of WNC Green Congregations, a network of faith groups dedicated to environmental stewardship.

“Religion contains stories about people getting unstuck,” he says, “and finding a way forward. And whether I’m religious or spiritual, the question is how much I identify with those stories to give me strength to do work in the world.”

Murphy’s sentiment is common among local and state faith leaders who are actively working for marriage equality, immigrants’ rights, voters’ rights, economic and environmental justice and more.

Bovee-Kemper has seen many people, particularly in the LGBT community, ostracized and hurt by the religious establishment, and says, “The idea that the right-wing fundamentalists are the only people speaking out about what God says about our world and how we should be moving and changing things … is a huge deficit.”

Rev. William Barber II, president of the North Carolina Chapter of the NAACP, says, “There has been a lot of work to undermine the moral discourse.” This year, Barber became the lead speaker at “Moral Mondays,” a series of weekly protests that arose in April 2013 to challenge legislation passed by the North Carolina General Assembly. Barber says that the moral voice of the people has been hijacked, and asks of legislators and other faith leaders, “How is it that you can call yourself a conservative Christian when you say so much about what God says so little, and so little about what God says so much?”

He explains: “Since John Kennedy and the civil rights movement, the extreme right made a deliberate decision to no longer allow a prophetic voice to have the moral microphone, [and] limited moral issues to three things: prayer in schools, abortion and homosexuality. We believe in making a direct challenge to that.”

Faith leaders are likewise joining the environmental conversation, which has largely been driven by the secular, scientific community. When Anna Jane Joyner, campaign coordinator for Asheville-based environmental group WNC Alliance, first got together with Richard Fireman, Grace Curry and Julie Lehman in February 2012, the informal group focused on bringing the spiritual dimension into environmental justice. By April, their conversation had evolved into WNC Green Congregations.

“The voice that the faith community brings is the moral and justice conversation: ‘Why is it that we care about these issues?’” says Joyner. “That’s something that [the faith community] can speak to in ways that people who are more interested in the economics of it or the science piece just can’t speak to. And there’s a great deal of power in that,” she says.

Steve Runholt, pastor of Warren Wilson Presbyterian Church and steering committee member of WNC Green Congregations, says that it’s his duty as a spiritual leader to speak out about climate change and sustainability. “In the Judeo-Christian tradition, it was the role of the prophet to speak truth to power, and not just to power, but to the people themselves,” he says. “Environmental justice is emerging as one of the 21st century priorities for that kind of prophetic voice.”

Inspirited action

Many of us tend to keep our spiritual beliefs and practices to ourselves. We want to be tolerant and politically correct, perhaps. But these spiritual leaders see no division between their public, political and spiritual experiences. In fact, to divorce these aspects would be to take out the very essence of the traditions they follow, and to reduce the value that spiritual practice offers them, they each emphasize.

“Make no mistake about it: Every major movement for social justice throughout time has had a significant moral inspiration and spiritual underpinning,” says Barber. “For me personally, I don’t know how to be Christian without being concerned about justice.” He reflects, “Jesus’ first sermon starts out with, ‘The spirit of [the] Lord is upon me to preach good news to the poor.’ But the word ‘poor’ is the Greek word ‘ptochos’ which literally means ‘those who have been made poor by systems of exploitation.’”

Bovee-Kemper also sees her spirituality as inherently political. She and her partner have repeatedly applied for a marriage license as part of the the WE DO campaign; she has worked with local nonprofit Defensa Comunitaria to get fair pay and fair treatment for workers seized in a 2011 Immigration and Customs Enforcement raid at Shogun Buffet, and she has spoken out at Moral Mondays both in Asheville and Raleigh. “What I believe about God is that when I suffer, when you suffer, God suffers with us, and the soul of the world feels those broken places the same way that we feel the broken places,” she says.

Prayer, in her view, is more than an entreaty — it is a covenant to take action. “My work is about helping the voiceless find a voice, [like] those children who got their food stamps taken away have no voice, [and] standing up and shining a light on that is … particularly what we are called to do when we believe there is something bigger than us — even if that’s not God.”

Though Barber, Bovee-Kemper and many prominent leaders of prominent initiatives come from a Judeo-Christian tradition, the leaders of other spiritual traditions are also bridging the gap between the spirit and the flesh.

For local members of the international organization Ananda Marga (the path of bliss), spiritual practice and social activism are the two halves that comprise the foundation of their lives. “First you need to address housing, food, clothing and medicine before you offer people meditation,” says Sid Jordan, director of the Prama Institute in Marshall and president of Ananda Marga Gurukula.

“Margis” (followers of this tradition) understand that social activism is a necessary aspect of their spiritual development and that their spirituality (education, yoga, and meditation) is a vital to their ability to offer true service, he explains. “The basic tenet of the universalism in yoga is that everything is an expression of God, and everything is divine. It doesn’t separate spirituality from our daily existence,” says Jordan. “Social action and spirituality are one; you are not going to achieve self-realization without serving others.”

Similarly, Nia Yaa, founder of Ra Sekhi Arts Temple and author of Kemetic Reiki One and Kemetic Reiki Two, practices her energy healing as a means for actuating social transformation. Her vision is to uplift and empower the African American community as a whole, and build the Garvey-Tubman Natural Living Center — a space of respite and healing for the downtrodden, as well as the center from which she will teach. To have a solid foundation, she says, there must be spiritual transformation on an individual level. “People of African decent have been through a lot of trauma. And that is why reiki is so important for this community. You can’t heal trauma with all of the pills that they are giving people for depression. … We need energy work to help move the trauma from all of those years of torture.”

Common ground

So, getting involved is a natural spiritual expression for these leaders, but they also see the way they take action —empathically — as a gateway for spiritual growth, where loving thy neighbor is much more than a meditation.

After the economic collapse 2007-08, for example, Rev. Amy Cantrell and her partner Lauren White wanted to mend the damaged social safety net. They wanted to create a sanctuary for the down-and-out, and a place for community building. When 39 Grove St. came up for rent in downtown Asheville, though they only had enough money for the deposit and the first month, they took the chance and opened the Be Loved House on Easter Sunday in April 2008.

“There’s a real danger in turning spirituality into something that is very vague and other-worldly,” says Cantrell. “Inner freedom and outer freedom are deeply intertwined. You can’t have one without the other. And at the same time, we can pursue some of the outer freedoms and lose the heart of it.”

She offers the Be Loved House “not as a shelter, but as a community. When people come here, they come home.” Cantrell adds, “They become part of the leadership, and carry the work in terms of helping open the house for hospitality, doing outreach to senior citizens, or going to the Moral Monday [protests] in Raleigh to stand up for the rights of the vulnerable.”

In June, the couple converted the top floor of Be Loved into the Rise Up Studio, a space where artists can create and sell their art.

Both spaces usher social transformation, and allow individuals to transform themselves, working with each other as family and supporting each other to pursue their dreams, Cantrell explains.

One thing that all these spiritually infused initiatives have in common are participants’ commitment to genuinely reach out to the opposing side, vilifying no one and understanding that unless activists are actually growing themselves through the process of unification, then the macroscopic change will remain untenable.

In 2006, long before the Moral Monday movement, the NAACP and 16 other organizations banded together to form the Historic Thousands on Jones Street/ Forward Together coalition. Over the next six years, the coalition reached out to as many other organizations as it could to create a movement for the common causes of justice and equal rights. The organizations weren’t all religious, they weren’t all even comprised of similar demographics, but by the time the General Assembly started rolling out legislation earlier this year, there were 160 collaborating organizations in the coalition, which helped create Moral Mondays.

Bovee-Kemper recalls a scene during the July 28 Moral Monday, after the General Assembly tacked a women’s reproductive health restriction onto a motorcycle safety bill: “I remember watching Dr. Barber and the existing NAACP stalwart crew on stage — and in came the pink-wearing, Planned Parenthood, radical women. And they just got scooped right up into the group,” she says. “That this is a movement which can encompass that broad a spectrum is very powerful to me.”

Barber says, “In the Moral Mondays movement, we believe that we must have a methodology and a message that doesn’t simply talk in these puny terms of liberal versus conservative. We need a language and a methodology that allows people to be human again.”

He continues, “That’s what the moral discussion does — it destroys the myth of isolation and suggests that we’re all intimately connected. And therefore, we have to have policy that has the kind of consciousness that honors that interrelatedness.”

“What activists sometimes get derailed in is slinging the same vitriol that they feel like they are receiving … and that removes the idea of commonality,” says Murphy. Through WNC Green Congregations, he’s involved with pressuring Duke Energy (recently merged with Progress Energy) to de-commission the Asheville/Skyland coal plant. But, Murphy says, “I shop at the same grocery store as people who work at Duke/Progress. These aren’t demons.”

Reaching out to the other side is more than a matter of spiritual discipline for Green Congregations clergy and other spiritual activists, he explains. It is a prerequisite for the comprehensive transformation they stand for.

The political activism, the vigils, the letters, the demonstrations and speeches are all a form of liturgy, and liturgy is a form of art, and art is a gateway for common experience and common cause, says Murphy. “Many people believe that experience is how we know truth, [so] what happens when we get in a situation where you disagree with me, is I hear you say my experience doesn’t matter. [But] art is a way to have collective, subjective experience.”

Murphy concludes, “I think art has the capacity to elevate us beyond the post-modern conundrum of people’s experiences being more important than other people’s experiences.”

Naturally, then, Murphy took his three kids to Mountain Moral Monday to experience what he saw as a powerful piece of art.

“Mountain Moral Monday was a feast of people from vastly different ideologies coming together out of a sense of purpose in wanting to have agency in a world they felt out of control with. The more common experience we can have, the more we can see each other as fellow human beings, rather than as this great competition.”

He says, “All authentic, deep community begins with shared vulnerabilities.”

As such, it was a shared sense of vulnerability in face of climate change and irreversible environmental damage that provided the foundation and glue for the clergy who created Green Congregations, Murphy explains.

Strength in spirit

Activism demands standing for something larger than oneself, and putting oneself on the line for it. But when activism is a form of spiritual devotion, an extra wild card is added into the mix, because no matter how much these folks may face arrest, ridicule, denial, or intimidation, there is something they believe they hold within themselves that is untouchable, that they will hold onto regardless of the risks they take here and now.

On Oct. 15, after four attempts at submitting a marriage license application in Buncombe County, Amy Cantrell and Lauren White’s application was accepted by Register of Deeds Drew Reisinger. Though the state has not yet approved it or the other license applications that were accepted that day, it was a breakthrough in the WE DO campaign that raised the hopes of gay and lesbian couples who had persevered for months in repeated attempts to register.

“We were one of the first couples in the South to have a marriage application submitted,” says Cantrell.

“The prophetic imagination creates space for implementation,” says Barber, “The first goal is to refuse to believe the myth of domination. It is to declare that your view that things have to be this bad — is, in fact, a myth.”

It seems sacred activism incorporates the best aspects of both the lion and the lamb: acting with bravery and conviction, but also with a humility that comes with the willingness to surrender oneself to being transformed.

“Nonviolence does not mean passivity. It means respecting people who differ from you,” says. Runholt. “Humility comes in when you are willing to have your opinion, your principles, revised by new information,” he says. “You have to have the openness of being changed yourself. Relationships are really how we move forward in bending the arc of history towards justice.”

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.