This Friday, Dec. 12, a most unusual movie opens at The Carolina. It also has a most unusual name — The Babadook — and it has something else: a 98 percent approval rating on Rotten Tomatoes (97 positive reviews out of 99). I don’t put much credence in the whole business of review aggregation. For a variety of reasons, I think it’s nonsense and one more step in the dumbing down process of film criticism. However, in the case of a horror film — that most disdained of genres — I think such a response merits a look, simply because it’s … well, unheard of. And I think it also deserves examination because that much unstinting praise ought to rightly raise your skepticism. I admit I approached The Babadook with a lot of skepticism. Three viewings later, I am one of its most ardent admirers.

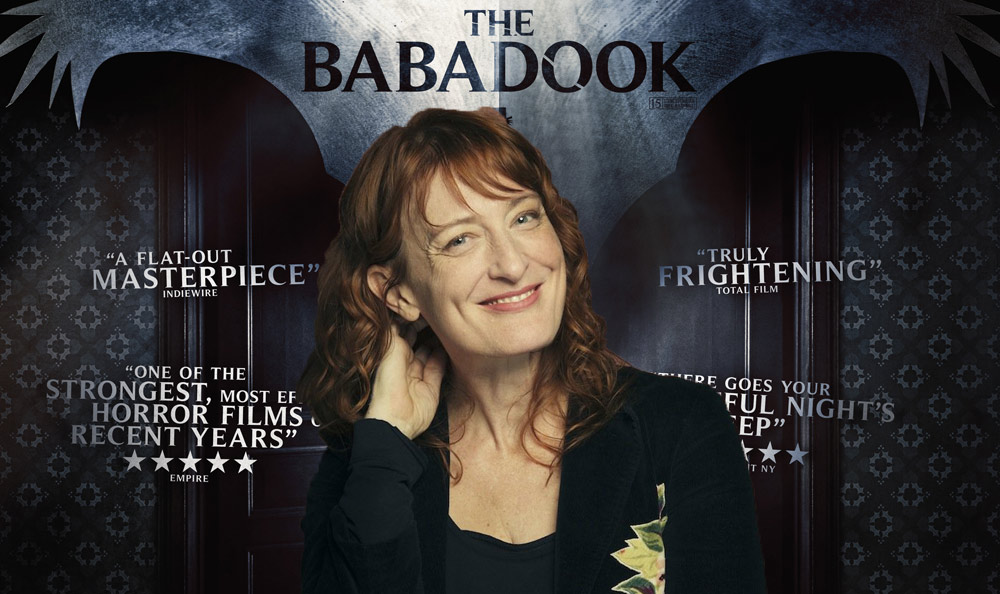

So when the opportunity arose to interview the film’s writer-director, Jennifer Kent, there was no way I was passing it up. I was allotted 20 minutes with her. We talked for nearly 40 minutes.

Ken Hanke: Congratulations — you have made a very fine film. I’ve seen it three times now.

Jennifer Kent (laughing): You’re a sucker for punishment!

Well, the first time I saw it, I had some issues with the earlier potions of it, but the second time I watched it I’m thinking, “This is a really smart film — there’s nothing wasted, there’s nothing arbitrary. It all actually does fit in.”

That’s great. You know, we were trying to be very lean with it — actually with what was there. So there’s not much padding as far as I can see.

I see almost none. I have to ask because I’m always shocked when I talk with someone who’s made what can be classed as a horror picture and it turns out they’re not — are you a fan of the genre?

I am. I watch a lot of it. I watched another film last night — one that will remain nameless. I always hope that they’re going to be good, and this wasn’t.

That is one of the penalties of being a fan.

Yeah, exactly. You always go with the hope, and it’s usually dashed, but, yeah, you keep going.

But you do sometimes get a surprise — and your film was easily the best surprise I got in horror all year.

Oh, thank you. You know, I’ve watched horror ever since I was a kid. Well, not a young, young kid, but I guess from about the age 10, 11, 12.

That sounds about right. I’m from the boomer generation of what they called “monster kids,” who came to the genre through monster magazines.

I love early horror cinema as well — from Jean Epstein’s The Fall of the House of Usher in the ’20s to Diabolique and Eyes Without a Face. This is stuff I’ll seek out, so, yes, I am a fan.

I’m glad to hear it. It’s easier to talk horror with someone who’s a fan of the genre than it is to talk to someone who made a horror film because they knew they could get it made.

I think that results in really mediocre films. Someone asked me yesterday why horror films are so looked down on, and I think it’s because there’s such a misunderstanding of the genre.

Oh, yeah, and I think you’ve made what I call horror-plus, because The Babadook is so much more than a horror film. But it still works as a horror picture — and I think that’s very important. I have to ask before I forget — is Mr. Babadook in any way inspired by the image of Lon Chaney in London After Midnight?

Yeah, absolutely. I will admit that image really impressed itself on me.

I think the thing about the Chaney films is that it’s more the stills from them than the films themselves.

Yeah, yeah. What I loved about that particular image — and you can also see it in the footage we used of him in the movie on TV from Phantom of the Opera — is that you can see that it’s a person’s face. It’s just a face that’s been distorted — without CGI obviously — but manipulated so that it looks human, but almost not. And I think that London After Midnight, shot with his face and his mouth pulled apart like that, is really frightening.

The TV sections of your film are what first really grabbed me — those and the pop-up book, of course. And you managed to include the first thing that ever really scared me in a movie theater — the “Drop of Water” segment from Black Sabbath when the old lady comes back to life. So I felt like this was really aimed at me!

Good for you!

It’s like you knew I would watch this, and so you put it in.

I love that piece — and I had to pay through the nose to get it, too.

I had wondered, because most of the footage seemed to be public domain.

You’d be surprised. We fought for a lot of stuff and got it. I really wanted a shot from the 1931 Dracula, but we couldn’t get it.

Well, it’s Universal, and they’re notoriously tight with their classic monster holdings.

Yes, exactly, but it’s still something I’m very proud of because everything in there is something that relates to what’s happening with Amelia, so I’m really happy with what we ended up with.

Even Skippy the Bush Kangaroo!

One of our favorites! It was funny because in the edit we thought, “We need something with Skippy here where they’re talking about a mother,” and sure enough we go to the first clip [and] we find it — it was synchronicity.

What I get is that there are certain horror touchstones — like The Shining (the film, not the book) — that are inescapable. I mean you almost have a variation on the baseball bat on the stairs scene, except that it’s a mother and son and not a husband and wife.

Yeah, the mother is supposed to be the protector, but here the situation is different. I don’t think it’s a deliberate reference, but when you’re dealing with areas of protection with a small child and that’s kind of exploited as well — along with that fear, “Is my parent going to protect me? Oh, no, they’re not.” — something else is going on.

It’s very well done. What I was wanting to say is that although your movie reminds me of other films, it is ultimately its own beast. I don’t feel like I’m watching a pastiche.

Well, the reason might be that I can’t help but be influenced because of my love for the horror film — my appreciation of it. But always when the reference stops, we need to make our own film. You know, the family of people that we collected, we were all aware that we wanted to create something new.

You’ve definitely created something new. There are moments in that film that are just astonishing to me. Plus — I love the fact that you know how to use a tripod.

It’s funny because I was working with a director of photography — and he’s amazing — but he has done a lot of hand-held stuff. So initially he was quite shocked that I wanted to go in a different direction, but then he really started to investigate that and develop that style. For me, the film is like a pair of hands around your neck that keeps getting tighter and tighter. There’s something sustained in that — not chaotic like hand-held can be chaotic. In effect, I think it would have released the tension in the film to have some much movement in the camera, and not increased it. I didn’t even care about what’s current or what’s modern; I just wanted the film to be true to the feeling of that woman.

I think that’s why it works. I really can’t say enough good things about this movie. It has so much in it that I just related to. Now, you may not — this is a background thing — but I get a deep, not too specific, sense of Polanski about this.

Oh, yeah, his films have made a huge impression on me, I think. The thing about Polanski — and also David Lynch, who’s a big influence for me as well — is that they’re masters at creating their own worlds. You know, I think about Rosemary’s Baby and that’s a New York that doesn’t exist anywhere else — except in that film. He’s a master at creating a specific world.

Well, I think you have created a world here. This has so much in it that I was not expecting. I really wasn’t — and there’s nothing that will scare me faster than people talking about a movie’s Sundance “buzz.” But I really was stunned by your film. Calling it the best horror film of the year does it a huge disservice, because it’s one of the best horror films of the century.

Oh, thank you. Thank you so much. That’s amazing.

Are you going to continue in this genre, or are you planning doing something different?

The two films that I’m currently writing aren’t in the horror genre at all. I tend to work from an idea, so I tend to work from something that really sparks me. So one of them is a story about revenge, and that’s set in Tasmania in the 1820s. The other is a heightened kind of drama — for want of a better word — about letting someone go and letting someone die. It has elements that are surreal because there are different realities going on — one is in the waking world and the other is in the mind of the person who’s in a coma. As a filmmaker, I have to be inspired by what I’m doing — the message has to be something that reaches me. I don’t think I’ll ever make something that’s just really, truly straight, but you never know.

I think you have added possibly the first completely non-camp — not that I have anything against camp — iconic horror figure since Freddy Krueger in the first Nightmare on Elm Street. I think there’s a certain feel to that one film that I get out of The Babadook, because you used so many floor effects. So much of this is solid. It’s tanglible. It’s real. And there were things in that first Nightmare that were lost as the budgets increased and the effects became more easily achieved. Much the same way, your film can be seen in terms of things that exist. They don’t look cartoonish.

Well, every effect in The Babadook is a practical effect. Some people have criticized the roughness of the effects, which is fine, but I don’t think they got what I was on about. I know teenagers are used to lots of CGI, but when people ask me, “If you’d had a huge budget, what would you have done differently?” And the answer is — not a lot actually, because the whole point is that they remain homemade so that they look like they’re happening in front of you. And also because it makes them look like part of the storybook world. We may have gotten better materials and more time to work on them, but ultimately it would have been the same effect. I get your point with the Nightmare films. It becomes about pyrotechnics after a certain point, and that’s a shame because the original is really frightening.

The first one is terrifying, and after that nothing really is.

No. Look, it’s personal taste, and after a certain point it becomes about money. In looking back on the history of horror, the best films that are keepers throughout the decade have all been independently produced — almost to a fault. There’s an independent vision running through those films. You know, they’re a little subversive and anarchic, and that’s why the films are what they are. And while we were making this I’d often say that to my producer. Films like Evil Dead and Texas Chainsaw Massacre and countless others like Nightmare on Elm Street have a independent spirit that we need to protect. When people ask me what’s going wrong with horror, I’d say that’s a big part of it. These kind of films can’t be made by committee. It’s impossible.

I think that’s true. I think that’s what’s going wrong with film in general sometimes. I’ve sat through three films this week that can only be described as Oscar bait. And these are fine, but they could have been made by anybody. They’re corporation films and they’re not in any way personal.

It’s kind of like mass-produced junk food. It’s pleasant. It works on your taste buds on some level, but it’s nothing to get excited about. It’s often cynical filmmaking as well where the motivation is strictly to make money. And you can find that in any genre.

I mean nobody sets out to deliberately lose money on a film, but making money can’t be your only motivation or even your primary motivation.

I’m hearing you, and I think there are always going to be people who are going to work outside of that mindset. At least I hope there are!

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.