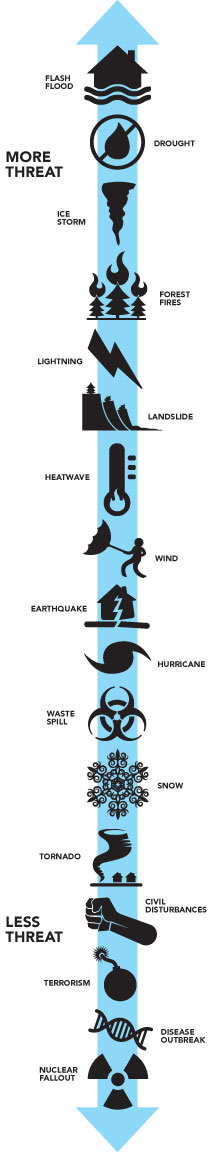

Even as the holidays come barreling toward us, some folks around the globe fear the mythical planet Nibiru may be doing the same and will trigger some unspecified cataclysm on Dec. 21. Notwithstanding the supposed end of the Mayan calendar, however, local agencies seem focused on preparing for more realistic potential threats. Although it may not be the end of the world, Western North Carolina does remain vulnerable to a wide range of natural and human-made catastrophes, including floods, blizzards, fires and even nuclear accidents.

And though the region’s long history is speckled with events that have caused varying amounts of mass suffering, the very nature of disasters entails a high degree of uncertainty. But while local experts say New Age Mayan prophecies are low on their priority list, they admit that there’s really no telling what or when the next big calamity might be.

When it rains, it pours

Rather than worrying about rogue planets, local experts say the far likelier hazards to fall from the sky are rain and snow.

Although Asheville is hundreds of miles from the nearest coast, hurricanes can bring torrential downpours and flash flooding to the mountains. The biggest natural disaster to strike the region in the last decade was the flood of 2004, reports Brian Scoles, chief public affairs officer for the American Red Cross Western Carolinas Region. In September of that year, hurricanes Frances and Ivan struck back to back, pummeling some parts of WNC with more than 18 inches of rain, recalls meteorologist Pamela McCown, who coordinates A-B Tech’s Institute for Climate Education. The torrents triggered multiple landslides and raging rivers reached record flood stages, wrecking 2,045 homes across the region.

Over the next several weeks, notes Scoles, the Red Cross opened 53 shelters, provided 2,533 people with safe places to stay, and prepared 73,000 meals. In Buncombe County, big swaths of Biltmore Village and Asheville's River Arts District were inundated, causing millions of dollars’ worth of damages.

Both those areas have seen significant new development since then, but that could make future calamities even more costly and dangerous, McCown points out. The Kessler Enterprise Inc. invested millions in the Grand Bohemian Hotel in 2009, siting it squarely in a part of Biltmore Village that was underwater five years before. "My first response was, whoa, you're going to put a high-end hotel right there where it flooded?" says McCown.

"The reality is, if you build in a floodplain, you're going to see some flooding at some point — and we can’t tell you when," she reveals. As development continues on steep mountain slopes, the risk of landslides also grows.

Meanwhile, New Belgium Brewing Co. is spending $175 million on a new 17.5 acre production facility in the floodplain in the River Arts District. Company officials say they'll build retaining walls and take other measures to prepare buildings to withstand the most severe kinds of floods on record for the area. But the climate, says McCown, may be changing in ways that make it hard to predict the extent of future flooding based on historical norms.

"Superstorm" Sandy, for example, pummeled the Northeast with massive flooding and dropped more than 2 feet of snow on mountaintops in the Smokies — a highly abnormal occurrence for October, she notes.

"As there appears to be an increase in extreme events, and the amount of water vapor available in the atmosphere for those things, you have to wonder: What's happened in the last 100 years may not be what's going to happen in the next 100 years,” says McCown.

Only the beginning

Frozen water falling from the sky poses different kinds of hazards.

Jerry VeHaun, director of Buncombe County’s Emergency Services Department, says the biggest natural disaster he’s seen in 40 years there was the March 1993 blizzard that dropped 14 inches of snow at the National Weather Service's Asheville Regional Airport station (the third-highest total on record) and much more in the mountains (Mount Mitchell reported 50 inches and 14-foot drifts).

Dubbed the "Storm of the Century," the extreme weather event delivered massive amounts of snow and rain from New England down to the Gulf Coast, causing more than 270 deaths across the eastern U.S. Locally, VeHaun recalls, transportation was paralyzed for nearly a week and several transformers blew out, leaving thousands of residents without electricity or heat as temperatures plunged into the single digits. Buncombe County recorded seven fatalities, he notes.

Hunkered down at work and sleepless for three days, VeHaun remembers, "We were trying to deal with people who didn't have power. If you were on oxygen, you couldn't generate oxygen. … Diabetics, trying to get medication to them if they were out. It surprised me that we didn't have more people freeze to death or die from heart attacks.”

Blizzards didn't pose any problems last year: It was the only winter since 1964 without measurable snowfall at the Asheville Airport, which opened that year. But the winters of 2009-10 and 2010-11 had total snowfall well above the 12.5 inch annual average — and loads of associated problems.

Meanwhile, the WNC-based Ray's Weather Center is predicting a slightly colder, snowier winter than normal, though its "Winter 2012-13 Fearless Forecast" also advises readers not to "put much stock in any forecast for the weather from two to five months out, including this one."

McCown agrees, saying forecasters are severely limited in what they can predict more than seven days out. "Meteorology is actually a relatively new science, and we're still learning how to do it — it is so complex," she notes. "Our atmosphere is really a fluid system, so we're really just beginning to get a grip on a lot of this stuff."

A lot of research, she explains, is now focused on determining whether the rising cost of severe weather damage is due to an increase in storms, in human population and development, or both.

In other words, McCown continues, "Is it because the weather's getting more extreme or because we have more exposure to these disasters, just because we have more people and built infrastructure than we used to?”

The "what if" business

For all the threats posed by natural disasters, it’s the more directly human-triggered scenarios that keep some first responders up at night.

On average, the Red Cross deals with two house fires a day in WNC and upstate S.C., helping provide emergency housing, food and other necessities. The threat increases in winter, notes Scoles, due to problems with home heating systems.

But in terms of plausible larger-scale catastrophes that Red Cross staffers train for, Scoles says his biggest fear is dealing with a nuclear emergency. There are eight nuclear power plants within 200 miles of Asheville — the distance within which the American Thyroid Association found "excessive" risk of thyroid cancer among Ukrainian residents after the 1986 Chernobyl disaster.

The closest plant to Asheville is Duke Energy’s Oconee Nuclear Station, just 62 miles down the road in South Carolina. The utility’s McGuire nuclear plant in Mecklenburg County, N.C, is 92 miles away, and the Cawtaba plant is about equally distant in York, S.C. If a major accident occurred at any of those plants, says Scoles, it would be unknown territory for local emergency responders.

The closest plant to Asheville is Duke Energy’s Oconee Nuclear Station, just 62 miles down the road in South Carolina. The utility’s McGuire nuclear plant in Mecklenburg County, N.C, is 92 miles away, and the Cawtaba plant is about equally distant in York, S.C. If a major accident occurred at any of those plants, says Scoles, it would be unknown territory for local emergency responders.

"We've never dealt with something like that before in a real-world situation,” he points out. “We've dealt with hurricanes, flooding, but not nuclear situations. We do train for that, but honestly, there are just some situations that you can never be quite prepared enough for."

VeHaun notes that an unknown amount of nuclear material regularly passes through Buncombe County on Interstates 26 and 40. Luckily, he says, we haven’t had any big nuclear spills so far; the hazardous materials released in local traffic accidents are typically limited to diesel fuel and gasoline.

On another front, VeHaun says his department has assessed the vulnerability of Asheville's water supply and determined that there are sufficient safeguards. "It would take a tremendous amount of something to contaminate our water supply by the time it goes through all the filtering processes,” he explains. “It's not a matter of dumping a gallon of something in the North Fork Reservoir.”

In terms of casualties, VeHaun says the worst incident on his watch was a 1981 food poisoning at the Ridgecrest Conference Center near Black Mountain, probably caused by contaminated ham. On July 25 of that year, some 308 people attending a Baptist convention there were rushed to five local hospitals for treatment, according to Associated Press reports. Luckily, no one died, "But they just thought they were going to die," he remembers. "If you've ever had food poisoning, you know how that is."

The memory of that ordeal has kept the need to move masses of patients in and out of local hospitals in the forefront of his fears ever since.

Despite backup generators and a contingency plan to haul water to Mission Hospital from different fire departments if needed, VeHaun says one of his nightmare scenarios is a terrorist attack or other catastrophe that forced an evacuation.

"You look at moving patients out of the hospital: Where would you take them? Could you move all of them?" he frets. "There's kind of a tiered system that the hospital's got worked out, where they take them different places. But some of them may be so serious you couldn’t move them. There's no single agency that could do all that."

Meanwhile, VeHaun says the prophesied end of the world on Dec. 21 ranks among the least of his concerns.

"If something like that happens, what can we do about it anyway?" he wonders. "If it's the end, it's the end."

Jake Frankel can be reached at 251-1333, ext. 115, or at jfrankel@mountainx.com.

Thank you for an informative article that should give everyone a lot to consider and hopefully to plan for. I was especially pleased to see these comments: “But in terms of plausible larger-scale catastrophes that Red Cross staffers train for, Scoles says his biggest fear is dealing with a nuclear emergency. There are eight nuclear power plants within 200 miles of Asheville