By July 16, 1916, the tail end of a hurricane, coming close on the heels of another one, had dumped 22 inches of rain on Western North Carolina in 24 hours, inundating the already sodden valleys. Mountainsides tumbled, and rivers overflowed their banks.

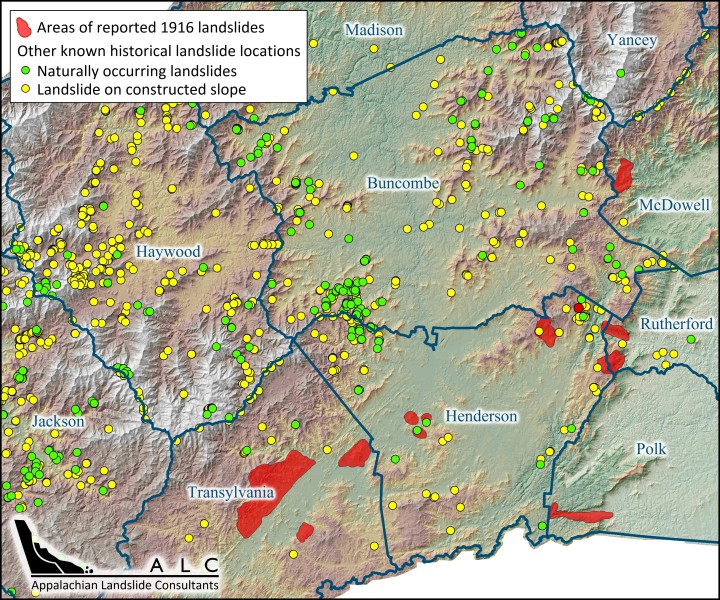

By the time the twin storms had passed, at least 300 landslides had been recorded and 80 lives lost. Dams and railroad trestles were destroyed, and residents in the communities along the French Broad, Swannanoa and other rivers were left with little except one another to rely on.

With the Great Flood’s centennial approaching, Henderson County filmmaker David Weintraub has produced a documentary, Come Hell or High Water, exploring the catastrophe through descendants’ memories, historical photos and contemporary accounts.

Xpress sat down with Weintraub recently to talk about the film, the flood’s impact on the region and the lessons to be learned. Here are excerpts from that conversation.

Mountain Xpress: What was your inspiration for making this film?

David Weintraub: I ran an environmental organization in Henderson County called ECO for a number of years. I started meeting with these elders in WNC and hearing their stories, and the 1916 flood often came up.

The stories were dramatic. I thought, “What a wonderful way to talk about protecting this community’s natural heritage — not from the vantage point of politics and polarizing people, but finding that cultural connection.”

It was important history, but it was also a story of how people lived their lives then. And with the centennial just around the corner, this was one way to tap into the soul of that wisdom from our elders and start some discussion.

What was it like for people living here as the floodwaters rose?

What’s striking, through all the families I spoke to about the flood, was the sound: People talk about it as if the earth was erupting. Blackness and loud noise… it sounded like thunder that never would end… half the mountain’s coming down. That just scared the heck out of people.

Very few people had any warning. It wasn’t like today: There was no internet or Weather Channel. All of a sudden, the sky opened up and the mountains released everything. Trees, soil, houses, pigs, chicken coops and barns were just floating down the rivers. The Swannanoa was a mile wide; the French Broad was four times its width.

The roads were dirt at the time and were all washed away. Hendersonville was surrounded by a lake: There was no way in or out. Biltmore and sections of Buncombe County were surrounded by water; Madison County was inundated. Not only did you lose your house and your food, but there’s nowhere to go. All you had were the clothes on your back.

An engineer in Asheville reported having seen 300 mudslides. We know at least 80 people died, but because so many people lived in the backcountry, nobody knows the exact number. Given the tremendous force of the rain, it’s amazing that there weren’t more folks killed.

What effects did the flood have on the region, economically, socially and environmentally?

We mostly had a self-sustaining agricultural society back then. When people started to plant in 1917, they found the topsoil had been washed away. You can’t go to Lowe’s and buy more — you just have to move on. Some people became sharecroppers in other parts of the counties; many just left. There was a mass exodus.

People learned where to build their homes and how to build them. Construction changed; In Asheville and many communities, rules began to be put into place regarding how close you could move to a river or stream.

It took months for Southern Railway, the only connection to the rest of the world, to rebuild. Trestles were gone, bridges were busted, dams were gone. It took five or six weeks to repair the tracks, which is lightning speed if you think about it. Anybody who had any skills at all was helping rebuild the railroads.

Somehow people got together again and found sanctuary in each other’s homes and the churches. Whoever had any preserved goods divvied them up and distributed them. And finally, everyone helped build back the homes.

What did working on this film teach you? Why is it important for people today to heed the lessons of 1916?

Part of it was just deepening my respect for the elders of WNC. Over the course of time, they developed ways of living that comported with nature. Elders are always prepared for the next storm. Often people who come here more recently lambaste the natives, but the natives aren’t the ones building McMansions on the top of mountains. We live our lives today as if everything’s fine and technology will save us, but my laptop has never tasted all that good, and the nutritional value of plastic is pretty poor.

There’s also the notion of land use: We can fight all we want about property rights, but nature is always going to win. Our job isn’t to try to avoid, disregard or work around it, but to work in concert with it. This is where we live — a 100-year flood happens every 20 years here. Since the last one was 2004, you might say we’re due. That’s not meant to frighten people, but we have to be cognizant that we can’t just willy-nilly decide where to live and where to plant.

The bottom line that governs all of this is the law of gravity. It applied in 1916, it applies in 2016, and it’ll apply in 3016. The flood demonstrates that in dramatic fashion. There’s a fine balance there, and that’s what we need to learn.

Come Hell or High Water: Remembering the Flood of 1916 will premiere Thursday, June 23, at Blue Ridge Community College’s Thomas Auditorium in Flat Rock, beginning at 7 p.m., with a discussion period and performance by the Rocky Fork Bluegrass Band afterward. Suggested donation is $5; advance tickets available at saveculture.org. For more information, call 828-692-8062. For future show dates, visit mountainx.com.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.