In less than 10 minutes, a doctor or nurse can get a read on a patient’s overall health and well-being just by checking a few key indicators: pulse, blood pressure, temperature and respiration rate. But how do you assess an entire community’s vital signs? And if you don’t, how will you know what the biggest problems are and how best to allocate scarce resources?

“There's so many different levels and layers of work that need to happen,” notes Buncombe County Health Director Gibbie Harris.

To get a better read on the county’s overall health status, Harris’ agency teamed up with its counterparts in 15 other counties and assorted hospitals in a regional partnership last year. In the first half of 2012, WNC Healthy Impact collected data, conducted phone surveys and facilitated community listening sessions to prioritize needs, track trends and identify attitudes.

Released in December, the results of those efforts both draw on and complement the countywide assessments all health departments in North Carolina must conduct at least once every four years to maintain their state accreditation. Based on those assessments, each health department must then craft an action plan; the Healthy Impact partnership seeks to help standardize the data different counties collect.

Also completed in December, Buncombe County’s 219-page Community Health Assessment (see sidebar, “What the Numbers Say”) hints at the kind of layered work Harris believes will be needed regionwide to substantially improve residents’ health and well-being. Other WNC counties, she expects, will face similar struggles in attempting to address two key areas identified by Buncombe’s assessment: access to care and chronic diseases such as obesity.

“They're not simple issues, and they're not going to be fixed with simple answers,” notes Harris, adding, “None of this work gets done in isolation.”

Collaborative efforts: Community Development Specialist Marian Arledge and Buncombe County Health Director Gibbie Harris say it will take the work of many agencies and collaborations to improve the health of Buncombe County. The department is currently working on a more comprehensive health improvement plan. Photo by Max Cooper

Buncombe County, however, aims to take its next action plan one step further. “For the first time, we’re going to create a more comprehensive improvement plan that takes into consideration more stakeholders and more types of work that's happening in the community,” Community Development Specialist Marian Arledge explains. Due this spring, the plan will address how well current practices are working, target duplications of resources and track specific projects to ensure accountability.

Still, cautions Harris, even the best county health department can do only so much.

“Health departments never have been and never will be the whole answer. A public health system engages and involves hospitals, doctors’ offices, community-based organizations, faith-based organizations, community leaders and coalitions,” she explains. “We want to help provide the information and the data so the community can make decisions about what the priorities are, and then we can help facilitate the process so we can develop that plan.”

Taking charge

Harris isn’t the only one hoping to ramp up Buncombe County’s health quotient. Frank Castelblanco’s plan focuses on education and community outreach.

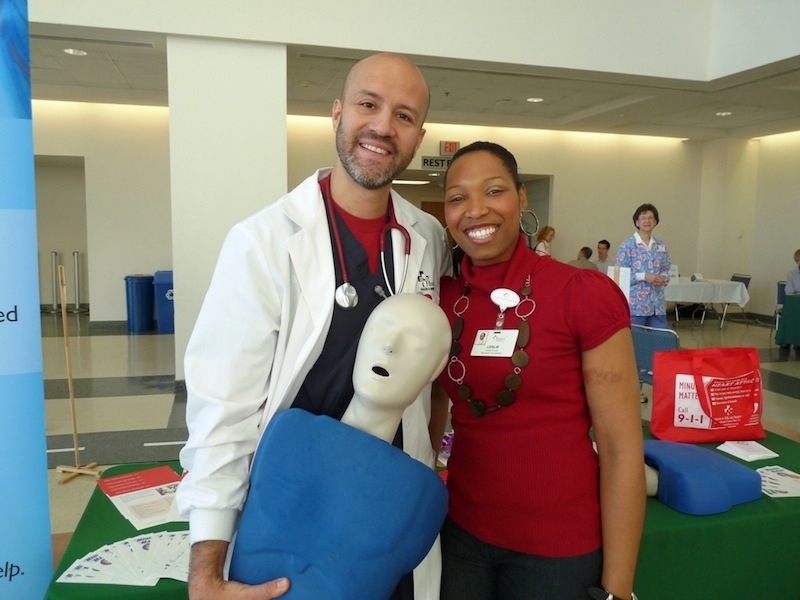

Since last fall, Castelblanco, the director of cardiac emergencies at Mission Health, has personally taught compression-only CPR to more than 1,200 county high school students. In addition, Mission provides free screenings to underserved communities.

“We go into neighborhoods where we know it's going to be lower-income housing. We know a lot of those residents do not have a primary-care physician because they don't have insurance — because they can't necessarily afford it,” Castelblanco explains.

Outreach with heart: Frank Castelblanco with Mission Heart Services along with Leslie Council with Asheville Cardiology Associates smile after teaching a CPR class. Teaching CPR classes is just one part of the outreach work done by Mission Heart Services. Other work includes offering free screenings throughout the community. Photo courtesy of Mission Health

In the WNC Healthy Impact survey, almost 75 percent of more than 300 respondents from Buncombe County cited cost or lack of insurance as the primary reason they didn’t get medical care.

But access to care is only one piece of the puzzle. Dr. Rebecca Bernstein, who chairs Mission Health’s Diversity Committee, says she’s as concerned about what happens to her patients after they leave the hospital as she is when they arrive.

“We care for all comers here even the uninsured but when I go to discharge them, my issues come up. When I say I need you to get to this health care provider or I need you to take this medication, there's some solutions in there, like $4 medications that I can try to find for my patients,” she explains. “But even if I do find them, sometimes they can't get to Wal-Mart to get them.”

“Preventive medicine,” notes Dr. Lucien Rice, “is not just before there’s anything wrong. It also occurs all along the way when you’ve already had some problems.” Guided by that philosophy, Rice and physiologist Lesli Andrews recently founded Asheville Medical Aging Prevention.

Mission Health shares that philosophy, says Bernstein, but applying it to different demographic groups entails additional challenges. The hospital, she notes, has collected data on race and gender in the past, but the Diversity Committee is now taking a closer statistical look at what kinds of “health disparities” (variations in health care and health outcomes among different populations) exist in Buncombe County.

“Disparities are complex, and our health care system is changing very, very quickly,” says Bernstein. “So we're going to have to think about creative and efficient ways to care for our population, to try to close the gaps in care.”

Thus, Mission’s outreach doesn’t end with free screenings. it’s also about building relationships and seeing patients follow through on their health needs.

“It’s your health; it’s your life. You have to take charge of it,” stresses Castelblanco. “That’s what I’m trying to instill in people when we go out and do these screenings.”

But finding the key that will inspire a particular individual to take better care of their health, notes Castelblanco, can take time — nearly four years, in one case he remembers.

“She’s in her 70s, and she’s raised children, grandchildren and, now, she's going to be raising great-grandchildren. But her blood pressure has always been high, and I just told her, ‘You need to take care of this for those kids. They need to have you around, because you are helping to raise them,’” he says, tearing up. “For years, I've seen her at every screening we do, saying, ‘I know, I know, I know.’ And finally, she made an appointment and actually went to the doctor and got the medication she needed.”

“Ideally,” he continues, “you want to head toward that wellness, that prevention component, where we're not being reactive but proactive about our health.”

Beyond Band-Aids

To that end, Dr. Susan Mims, vice president of Mission Children's Hospital, is looking ahead to the next generation. Educating parents and children about the critical importance of establishing healthy habits early on, she believes, could avoid some of the chronic ailments county residents and their caregivers are now dealing with.

“We're putting a Band-Aid on a lot of [things that] could be prevented,” says Mims, the former medical director of the Buncombe County Health Department. “It's really about getting the message out there that sugar-sweetened beverages at an early age speaks to obesity, speaks to dental health, speaks to a lot of things.”

In the meantime, though, there’s a high probability that the people who aren’t being reached, and who lack access to primary care, will wind up in the emergency room, says Stephanie Whitaker, interim director of Mission Hospital's Emergency Department.

“The Emergency Department isn’t just for emergencies anymore: It's also for those primary-care needs,” she reveals. “We are here because someone's emergency is their perceived emergency. They may not have lost a limb and be bleeding, or they may not have been in a terrible car accident or are having a stroke or a heart attack, but we're here to treat everyone.”

That shift, however, carries a high price. “We have seen a steady increase in Emergency Department visits,” notes Whitaker. The 61-bed facility now sees upward of 100,000 patients a year (about 300 per day, on average), she estimates. “We end up utilizing our hallway beds a lot of times, because every day, we're full.”

Compounding the logjam is the fact that emergency services can’t operate on a first-come, first-served basis: Patients with more critical needs must be tended to first.

“We don't see a lot of patients who come to us when they first start with the sniffles or minor illnesses: They try to treat themselves at home, using homeopathic or over-the-counter remedies; oftentimes they don't have primary care available. So when they do arrive in the emergency room, they're often sicker than [people in] communities with more primary-care resources,” Whitaker explains. “We'll always be here, but it's just better for patients, and it's also more affordable, if they can find that primary care first.”

At the same time, the Emergency Department has also become the de facto catchall for mental and behavioral health problems. One key reason, she notes, is the state-mandated mental health reform in 2001. With fewer mental health facilities and resources, more of these patients are now ending up in emergency rooms.

In 2010, psychiatric disorders were the most frequent diagnosis resulting from Emergency Department visits in Buncombe County (20.08 percent), far outstripping the next most common problem (chest pain and ischemic heart disease, 11.79 percent), according to public health data collected via NC DETECT.

“Sometimes the Emergency Department is controlled chaos,” says Whitaker. “Everyone's coming in with a different need and different stressors.”

Owning up

Although local physicians, other health care providers and community leaders may differ over how best to address Buncombe County’s “vital signs,” for Health Director Gibbie Harris, the fundamental challenge is clear.

"These are communitywide issues that the community has to own if we're going to make any difference," she maintains. “When a community ‘owns’ an issue, we all recognize our shared responsibility to take action. For example, at the recent Weight of the Nation event, a dozen organizations helped bring together more than 200 individuals from diverse sectors to address healthy living in our community.

“When our community takes ownership of the issue of healthy living and obesity, we see one another adding miles of greenways for physical activity, purchasing more local produce, taking our children out to play, and coming together — because the obesity epidemic cannot be the responsibility of a single institution or individual alone (see sidebar, “Connecting the Dots”).

“As we move toward the community ‘owning’ our health outcomes, we are moving toward a collective-impact approach in which many entities work toward a common goal, sharing our successes and challenges.”

In other words, “We’re all part of the solution.”

Send your health-and-wellness news and tips to Caitlin Byrd at cbyrd@mountainx.com or mxhealth@mountainx.com, or call 251-1333, ext. 140.

What the numbers say

Buncombe County’s 2012 Community Health Assessment identified four priority areas. Here are some key stats drawn from that assessment and other sources, grouped under each of those priorities.

Women's pre-conception health

The county’s death rate for white infants was 4.7 per 1,000 live births. For African-American infants, it was 11.7. North Carolina’s infant mortality rate is among the highest in the U.S., ranking 46th out of 50, according to the 2011 America’s Health Rankings.Healthy weight and healthy living

• 91 percent of Buncombe County respondents said they don’t eat the recommended five or more servings of fruits and vegetables per day. — telephone survey conducted by WNC Healthy Impact

• More than nine out of 10 Buncombe County residents polled said they think it's important that communities: make it easier for people to access farmers markets and increase public access to physical activity spaces such as trails, parks and greenways. — WNC Healthy ImpactImprove children's health and early child development

The average wait time for families seeking child care subsidies in Buncombe County has increased by two months during the past year. In September 2012, Buncombe County served 1,969 children and had 1,285 children on the waiting list. — Community Health AssessmentAccess to primary and mental health care

• 75 percent of Buncombe County residents surveyed cited cost or lack of insurance as the primary reason they didn’t get needed medical care.

• 32 percent cited cost or lack of insurance as the primary reason they didn’t get needed mental health services.

• 15 percent said they weren’t able to fill a prescription they needed at some point in the past year. — WNC Healthy Impact

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.