Black Mountain College is known best as an innovative, experimental liberal arts institution that attracted such luminaries as John Cage, Robert Rauschenberg, Merce Cunningham and Willem de Kooning, among others.

Craft and design are not on that short list, but the Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center intends to strengthen the craft connection with its current exhibition, “Shaping Craft & Design,” and the fifth-annual ReVIEWING Black Mountain College conference, to be held Friday through Sunday, Oct. 11-13, at UNCA's Reuter Center.

Each year, BMC+AC’s conference and corresponding exhibition work in tandem to invite and propel discourse on artists and concepts cultivated at the college, which operated between 1933 and 1957. This year focuses on BMC’s impact on studio craft and design and the often-void middle ground between them and fine art.

“People know and like to talk about the painting legacy at Black Mountain College,” Katie Lee Koven, the exhibition’s curator, tells Xpress. You don’t have be entrenched in art history to recognize names like Rauschenberg and de Kooning and Josef Albers — their names and artwork fall within the canon of mid-century American behemoths. “But there was a craft and design legacy too,” she says.

Defining that legacy is the backbone of Lee Koven’s exhibition and the goal of the conference, which includes a weekend-long itinerary of topical and esoteric lectures, panels and film that outline BMC’s national and international reach in the studio crafts movement (and the influence of WNC institutes like Penland School of Crafts on the college).

The exhibition, much like the conference’s liineup, features a smattering of works and media representing both traditional craft and fine art.

Ceramic works by Robert Turner, Peter Voulkas, David Weinrib and Karen Karnes rest near furniture by A. Lawrence Kocher and Mim Sihvonen and textiles by Anni Albers and a handful of students and understudies. Etchings and prints by Josef Albers and Jack Tworkov and sculptures by Kenneth Snelson and R. Buckminster Fuller span the would-be no-man’s-land between functional and traditional “aesthetic” works, that is, non-utilitarian pieces.

In between the craft and fine-art works rests a wooden loom and a few dozen bits of period ephemera such as classroom photographs, architectural drawings, letters and notebooks, which contribute to the historical aspects of time and artist-to-artist communication.

The sheer quantity of works and accessories should have the appeal of a survey show. But that’s not the case here. Rather, it’s a web, a visual assemblage of shared materials and techniques that represent the artists’ relationships and the school’s immersive, yet freeform educational model.

The collection spotlights artistic similarities while exposing individuals’ creative and stylistic deviations from their predecessors. “It’s about showing those creative pursuits and exploring work made by craft artists who were challenging barriers between art, craft and design,” says Lee Koven.

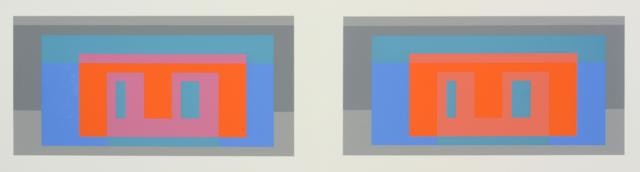

She attributes BMC’s attention to materials and design to the school’s shared educational vision, the breadth of their arts offerings and a deep connection with the Bauhaus school in Germany. That connection came from two artists and faculty members in particular: Josef and Anni Albers.

The Alberses joined the BMC faculty in the fall of 1933 after fleeing Nazi-controlled Germany. Anni taught weaving. Josef taught design and painting courses and headed up the art department for the duration of his BMC tenure (1933-1949). Both arrived from the just-closed Bauhaus school, which Anni attended and where Josef was first a student, then a teacher.

“Josef had a preoccupation with materials, a respect for them that relates to that same preoccupation that craft artists have,” Lee-Koven says. That respect for materials came from his Bauhaus background. At Bauhaus he worked with stained glass and furniture before he began teaching foundational, crafts-based design courses.

The baseline philosophy of both modern architecture and the Bauhaus school, which the Alberses promoted at BMC, was that an object's form follows its function. And so his courses bound together craft’s functionality and reverence for materials with fine art’s design orientation.

BMC, which also combined John Dewey’s student-driven educational philosophies, had only two required courses: one on Plato and one on foundational concepts taught by Albers. The latter covered design and materials that, according to Lee-Koven, “placed an emphasis on the overlap of practices by designers, artists and craftspeople.” Put another way, the lines were intentionally blurred to keep the curriculum heavily intertwined, yet open-ended. After fulfilling the required courses, students could branch out into their own fields of study.

“Craft flourished in the democratic community,” says Alice Sebrell, BMC+AC’s program director. The variety of resources and ability for ample student input became natural surrogates to craft’s inclusive and materials-driven nature. “They might not have separated craft from Art — with a capital A,” she says, “but it was all part of the total experience.”

Albers emphasized the means to the end, rather than the result.

“It’s about experimental process, not about the end product,” says Lee Koven. “As an experimental liberal arts college, that makes complete sense. They were learning concepts that they would take with them forever.”

“Shaping Craft & Design” is on view through Jan. 4, 2014. For tickets and more information on ReVIEWING Black Mountain College 5: Shaping Craft & Design, visit http://www.blackmountaincollege.org.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.