- Dabashi describes the collection as a socially and politically comprehensive view of the Iranian Revolution. It’s a museum in and of itself, he said, “one of a national revolutionary consciousness — a cataclysmic event that included millions of millions of people.” Posters courtesy of Carlos Steward and Cynthia Potter

There are roughly 200 connections between Asheville and the Iranian Revolution. Really. It just so happens that one of the largest privately held collections of posters from the revolution, nearly 200 in number, resides here.

For the next two months, 146 of these posters are on view as part of In Search of Lost Causes: Images of the Iranian Revolution: Paradox, Propaganda and Persuasion, a multi-institutional exhibition series showing at three institutions across Asheville.

Thirty posters hang in UNC Asheville’s Ramsey Library, 10 line the walls of Firestorm Cafe and Books, and the remaining 106 fill up two floors in the Phil Mechanic Studios’ Flood and Courtyard galleries in the River Arts District.

At an Oct. 17 opening reception at UNCA, Dr. Hamid Dabashi, an Iranian-born scholar, cultural historian and the Hagop Kevorkian Professor of Iranian Studies and Comparative Literature at Columbia University, delivered a lecture on the collection’s historical legacy and contemporary significance. Dabashi, aided by a N.C. Humanities Council grant, traveled to Asheville to co-curate the exhibitions with Steward and give a series of lectures.

The collection belongs to Carlos Steward and Cynthia Potter, who operate the Courtyard Gallery in the Phil Mechanic Studios. They received the posters in 1999 as a gift from a source they will not disclose. Dabashi believes that donor was likely involved in the inner workings of the revolution, which took place between 1977 and 1979.

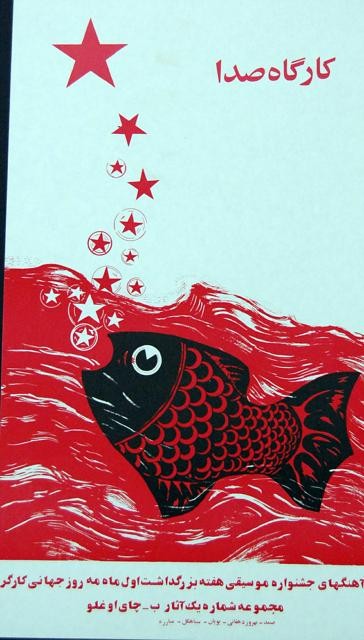

The images unfold in every shade imaginable, though black and red — colors long associated with revolution — are dominant. Most of the posters feature a cast of heroes and villains that include governmental officials, individuals, and groups of activists and laborers. The pictures depict individuals who are wounded, dead or dying — both innocent and guilty. Some wield AK-47s, others pray. Text runs throughout most, appearing in Arabic, French and English, among other languages.

Several works celebrate music, farming and working-class peasantry, while others criticize U.S. involvement in the 1953 coup that ultimately set the revolution in motion.

“They’re the perfect marriage of art and politics,” says Mark Gibney, a professor of political science at UNCA, who helped anchor the exhibition.

Dabashi describes the collection as a socially and politically comprehensive view of the revolution. It’s a museum in and of itself, he says, “one of a national revolutionary consciousness — a cataclysmic event that included millions of millions of people.”

Steward initially contacted Dabashi, via email, in June 2010 after reading his book Staging a Revolution. The book had information on the revolution’s graphic and artistic works, Steward told Xpress, “and a lot of them were similar to these posters.”

Steward’s message was short and direct, according to Dabashi: He had nearly 200 posters from the Revolution — was Dabashi interested in looking at them? Dabashi admitted that he was initially hesitant to jump into the matter. He and Peter Chelkowski, a colleague from New York University, had spent years amassing similar imagery from the revolution. They compiled that imagery and wrote Staging a Revolution.

Neither Dabashi nor Chelkowski had come across such a large collection of ephemera, posters specifically, in such pristine shape. “They were all in mint condition,” he says, “and I thought, ‘How do you have these in Asheville, North Carolina?’”

“Streets and lampposts,” Dabashi says, “that’s where these things belonged.” In other words, the posters should’ve been ragged and full of staple, nail and tack holes — not in the flawless, fresh-pressed condition of Steward and Potter’s Collection. Either that, or they would've been trashed decades ago.

“The posters [are] remarkably representative of the revolution,” he says. “It’s proof that the revolution wasn’t from just one ideology.” Instead, there were many factions working together to overthrow an oppressive power.

And these posters didn’t just come from Tehran, he notes. They were also made in surrounding countries. They hailed from Eastern Europe to India to London — even Salt Lake City. “Anywhere where there were Iranian students,” he explains.

The artists and the revolutionaries saw their cause in other movements, Dabashi says. They promoted movements from all over the globe: women’s rights in the Middle East, labor rights and even the civil rights movement in the United States. One poster features an outstretched Iranian arm beside a black arm, both clad in broken shackles.

According to Dabashi, the collection has universal themes. “They carry … a relation to any movement or ideological revolution,” he says. And because of that, they draw us into comparing them to the present.

Dabashi no longer looks at such collections as stagnant placeholders of an era. Rather, these collections carry contemporary weight. “It’s a way to touch base,” he says, “to revive the cosmopolitan disposition.”

Both Dabashi and Steward intend to keep these posters in motion. They’ll travel from Asheville to Los Angeles, then back to New York before heading overseas.

During the lecture’s Q&A session, several attendees noted the shift in media presentation, asking if the digital age had snuffed out print media in the modern revolutionary landscape.

“I’m neither antiquarian nor beholden,” Dabashi says of the posters’ vintage look. “The fact is, the digital age is no joke. It has traction, both negative and positive.” The immediacy and global reach of such social-media outlets like Facebook and Twitter, he says, is powerful, immense — unstoppable even.

“We must be aware of the material significance,” he says. “But the ideals are the same, only the technology has changed.”

what: In Search of Lost Causes: Images of the Iranian Revolution

where: Flood Gallery (109 Roberts St.) through Friday, Nov. 29, and Firestorm Cafe (48 Commerce St.) through late November. Exhibition catalogs are available for purchase at all locations.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.