This is the final installment of a three-part series. Read Part 1 here and Part 2 here.

Local author Charles Blount is on a mission: To shake hands with children. “I say, ‘Do you like to read, because reading is important.’ … I say, ‘How many authors have you met?’ They say, ‘None,’ and I say, ‘Well, you just met one.’”

Authors, he says, owe the community a piece of themselves. Above and beyond being a writer, though, Blount sees himself as an African-American writer and part of a tradition that is “always about sharing, sacrificing and standing for what you believe in, and knowing that you might have to be the one to step up and do it.”

He adds, “Globally, as an African-American, I’m part of a village. … And if I’ve made it, who do I give thanks to? Nothing a person ever does is on their own.”

That’s not to diminish the obstacles that must be overcome. “Though all artists suffer isolation associated with their craft, African-American authors have special concerns,” wrote Kenneth L. Harrell Jr. in his 1998 paper “From Acceptance to Autonomy: Ralph Ellison’s Engagement with Black Freedom in Invisible Man.” The then-UNC Asheville senior was completing a Bachelor of Arts degree with a major in literature. “After all, the existence of black authors defies notions of innate black inferiority that continue to plague American society. Therefore, black authors labor under a special burden; they continually challenge the notion that African-Americans are incapable of writing good literature.”

A healing element

While poet and spoken-word artist Nicole Townsend acknowledges that there is a writing community in Asheville, and her work has been welcomed, “I don’t feel like I fit into it,” she says. “I don’t feel really connected to the writing community, and I think a lot of that is cultural.”

She once tried to join a local writers group and, while she received helpful tips and feedback, “when I write, I want to be able to connect with people about the content, and it’s hard when someone’s just judging the structure,” she says.

To forward her work in her own way, Townsend launched Existing While Black, a spoken-word performance. Raw, soulful and shot through with brutal truth, the show not only spotlights Townsend’s poetry but also gives platform to other nonwhite artists, such as singer-songwriter Lyric, who performed at the November installation. The inaugural production, last April, was emceed by community activist and newly elected City Council member Sheneika Smith.

Last year, Townsend told Xpress she birthed Existing While Black out of “wanting a platform to where we can go deeper and talk about things that are uncomfortable, that hurt, and that make people angry.” She continued, “When you use an art form, people are more accepting of it, because art is supposed to challenge you. … There is a healing element when messages come through art.” She’s currently putting together a Southern tour of the show, tentatively planned for September

Blount, too, sees healing in writing. “Love and compassion: That’s what I’m about,” says the Bronx-born writer, though he didn’t have the most supportive start. He spent time in group homes and detention centers.

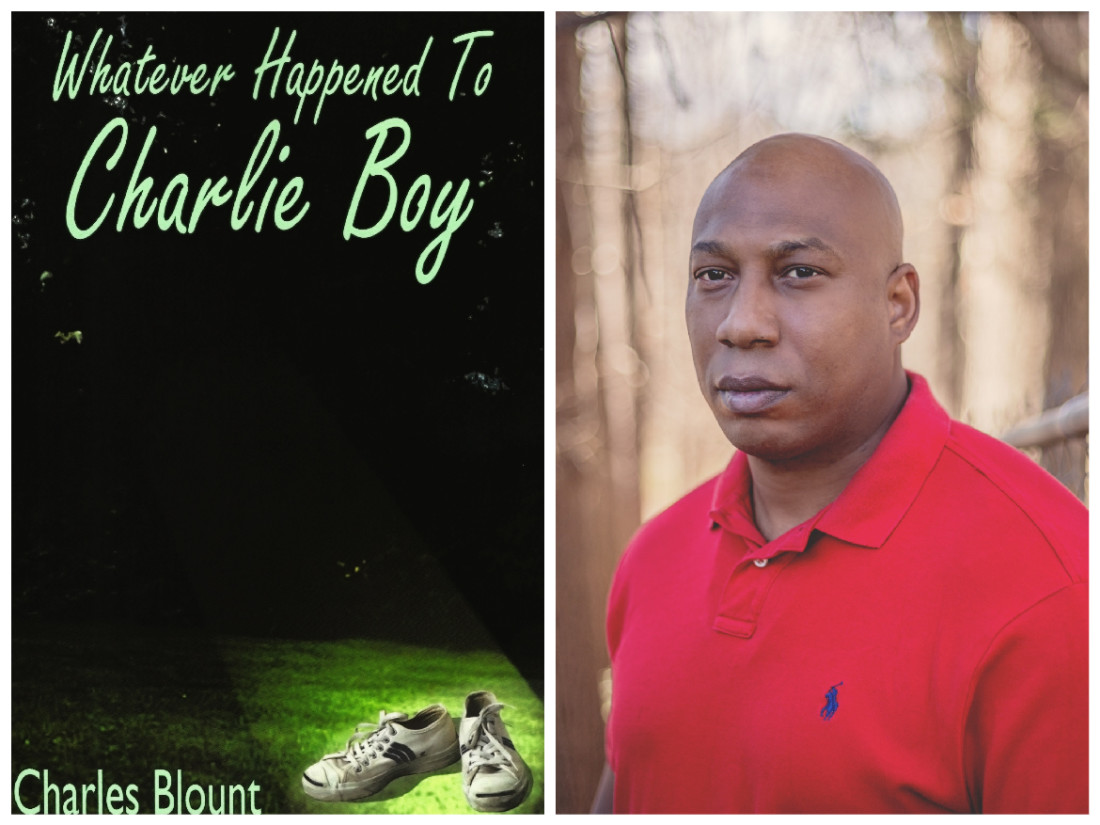

“Life has a way of cultivating you,” says Blount who, at the suggestion of a girlfriend, parlayed those experiences into his debut book, Whatever Happened to Charlie Boy, which he published in 2004. The author has since penned two more titles (Daddyhood in 2008 and Purpose in 2017), is at work on a new book and is writing a screenplay based on Charlie Boy.

“Something sparked about being a writer,” he says of his initial foray into the art form. “Things happen in due time, but when it’s your time, it’s just your time.”

New voices

Poet Damion “Dada” Bailey also began writing as a response to life circumstances. As a young person, his dream was to become a police officer but, at age 15 or 16, when he started growing facial hair and transitioning to manhood, the police he’d once admired began treating him with suspicion. “There was a certain amount of harassment,” he remembers. “It makes you militant. It makes you anti-police.”

He expressed himself through music — first West Coast rap, such as NWA. But when, at 18, Bailey became a father, he decided to go to college for business in Greensboro. There, he was exposed to poetry open mics. Before that, “I wasn’t familiar with a poetry scene in Asheville, just a rap scene,” he says. “I started putting all this poetry I had in notebooks.” He collected that work into what would become his first publication, Often Thoughts.

Bailey currently lives in Charlotte, where he’s the proprietor of The Wonderful World of Plumbing and is planning to illustrate an educational book about plumbing to encourage children — especially those of color — to consider a career in the trade. “I’ve knocked on a couple of doors where people were shocked to see a black guy,” he says. “I want to get rid of the [good ol’ boy] stereotype.”

Kids need positive role models across the vocational spectrum. For Asheville-area teen writers and performance poets, programs like HomeWord and Word on the Street/La Voz de los Jovenes magazine “are cultivating young people who will [create a literary] scene as they journey into adulthood,” says Townsend.

But will those youth artists stay in Asheville? “If we don’t cultivate a scene for them, it would be easy for them to pop over to Atlanta or Durham,” Townsend cautions.

So what does Asheville need? “A lot of things are about culture,” says Townsend. “In order to attract people, you have to have something in your establishment that they’ll gravitate toward.” She suggests literary institutions bring in nonwhite writers, hold more events centered on people of color and — in the case of bookstores — survey local nonwhite consumers to find out what books they’d like to purchase.

“Right now … I’m educating myself about a lot of things that are going on politically and a lot of things that have happened throughout our history,” says Townsend. “Those books, for me, are mostly found at Firestorm or Barnes and Noble.”

Not the same struggle

If local bookstores have not proved to be welcoming spaces for writers of color, neither have literary events such as open mics and readings. “I don’t feel like the mainstream is really mainstream for everyone,” says poet, playwright and author Monica McDaniel, who has found support within a network of friends and extended family. But beyond the African-American community? “It’s a bit tougher,” she admits.

Talking about equality is not the same thing as creating an environment of equanimity. “Will I feel welcome at the venue? Will listeners treat me the same way they treated the person before me? Will they relate to my work?” McDaniel asks. “It’s a lot of factors.”

She continues, “We want to be, as a city, more diverse, but we don’t know how to be diverse. … It’s a huge issue, and it’s been an issue for my almost-40 years of living here.”

Bailey returned to Asheville for the launch of his last collection, My Journal, My Journey. The release party for that sophomore project, held at Club 828 (now New Mountain) was “a major turnout,” he says. “I read a poem [and] had a moment of silence for people who were gone but not forgotten.” Coming back to his hometown, he says, “is my way of giving back.”

Despite a strong turnout for that book launch in a nontraditional venue (not a bookstore or library), Bailey doesn’t necessarily feel at home in “white” literary spaces. He remembers attending a couple of predominantly white open mics and didn’t read “just because the style and content was so different,” he says.

Bailey says that for some in Asheville, there’s been a sense of reluctance to intermingle outside of their immediate communities. “If you’re brought up in Hillcrest, it’s not often you just walk uptown and go to drum circles and things like that,” he says. But, he concedes, lately Asheville seems more integrated to him that it has in years past.

As for the segregated writing scenes, “It’s almost like hearing a pop song verses a slave spiritual,” Bailey says of white literary events versus those featuring writers of color. In works by the latter, “there’s a lot of emotion, sometimes pain, and superstrong, passionate expression. It derives from struggle, and the struggle in the black community is not the same struggle as the white community. The stories don’t parallel and they don’t coexist.” But, he adds, it would be awesome if they did.

Taught and felt

Supported or not, nonwhite writers still find platforms for their ideas and creative voices. Local poet and visual artist James Raysean Love wanted to study writing, in part, because “in history, as far as I know, African-Americans were the only group that was legally denied the right to read and write,” he says. The Burlington native started to pursue a degree at Morehouse College in Atlanta, a historically African-American institution. But after he didn’t make the basketball team at that school — the sport was his main focus — he transferred to Warren Wilson College.

![LESSON LEARNED: Warren Wilson College graduate James Raysean Love explored the connection of poetry and visual art at the local school, but questions how nonwhites are treated and represented in writing programs and in published work. “A lot of my people are brilliant, they’re creative, and depending who’s selling the story will [determine] what you get out of it,” he says. Photo by Parxx](http://mountainx.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/James-Love-720x539.jpg)

Love’s Christian faith helped him weather the cultural shift, too. At times, he says, he slept in the college’s chapel, which became his place of refuge. Writing also served as a shelter: Love studied with poet and painter Omari Fox, who was a guest at Warren Wilson at the time, Lorrie Jayne and Gary Hawkins “who really helped me see … the relationship between poetry and the visual arts.”

Although Love returned to Burlington after college, and then pursued a basketball opportunity in Texas that didn’t pan out, he’s now back in Asheville. He recently performed in Left Behind, a stage production by McDaniel, and is contemplating his next steps. “I’m not interested in art that [only] passively entertains you,” says Love. “I’d like to introduce art to places like Pisgah View [Apartments, Livingston and] Erskine[-Walton], Dearverview [Apartments] … not to suggest [the residents] aren’t already whole, but to give them other outlets. … I think art and poetry can be big to opening the mind up to, ‘This is all a creation.’ … Art and poetry help you open up to possibilities.”

Love is considering a Master of Fine Arts in Writing — his alma mater is well-known for its program — but points out the expense of such degrees can be prohibitive. And then there’s the issue that many MFA programs are overwhelmingly populated by white students and teachers. “It concerns me that the human is only acquainted with the white, and the others are just spectacles to be studied,” he says.

Love also has an aversion to racial bashing and victim narratives, he says. “A lot of my people are brilliant, they’re creative, and depending on who’s selling the story will [determine] what you get out of it.” What he is interested in is, “What’s fresh? Can we break through that matrix real quick? … I’m not asking for ‘Kumbaya,’ I’m just asking for authenticity.”

A beautiful craft

Many writers of color are asking to be judged on their own merits, rather than the merits determined by a system constructed to exclude their voices. “The style has to match the author’s work so it keeps its powerful flow and tells the story through the eyes of the author,” says Blount. He once received a review that claimed, while his story was good, the writing wasn’t on par with “professional” authors.

“I didn’t write the book [so] it could be up there in the writing world. … I don’t compete with writers,” says Blount. “I try to reach as many people [as I can] through the writing. It’s readable and comprehensible so they don’t have to go looking certain words up in the dictionary.” He knows his audience and crafts his work toward their tastes. And, as a self-published writer, Blount can do exactly that, rather than worrying about industry trends or style points from outside influences.

When it comes to working with an editor, he says, “What it boils down to is having someone who will not change the story and will not take away its powerful essence of delivery.”

He continues, “I don’t need someone to validate my work. It’s all the basics and foundation of sharing. As long as I’m on that track and have that passion … it’s a beautiful craft.” His work, he says, gets read by the people who need it.

Resilience propels Asheville’s nonwhite writers forward in their work. For example, even as Bailey builds his plumbing business, poetry remains on his mind. “I have a bunch of snippets, and I have a bunch of torn pages with stuff on it,” he says. “Right now … I’m still putting it in a notebook. But I’ll probably — in the next year an a half — come out with my third self-published book.”

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.