As a child, Michael Hettich‘s father regularly read poetry to him — works by T.S. Eliot, Robert Frost and William Butler Yeats.

“But it wasn’t until my second year in college, when one of my professors read a translation of César Vallejo‘s ‘Black Stone Lying on a White Stone,’ that I knew I wanted to dedicate myself to writing poetry,” the Black Mountain-based, award-winning poet says. “The poem was so haunted and wild and viscerally alive that it made me feel regions in myself I don’t think I’d ever felt before.”

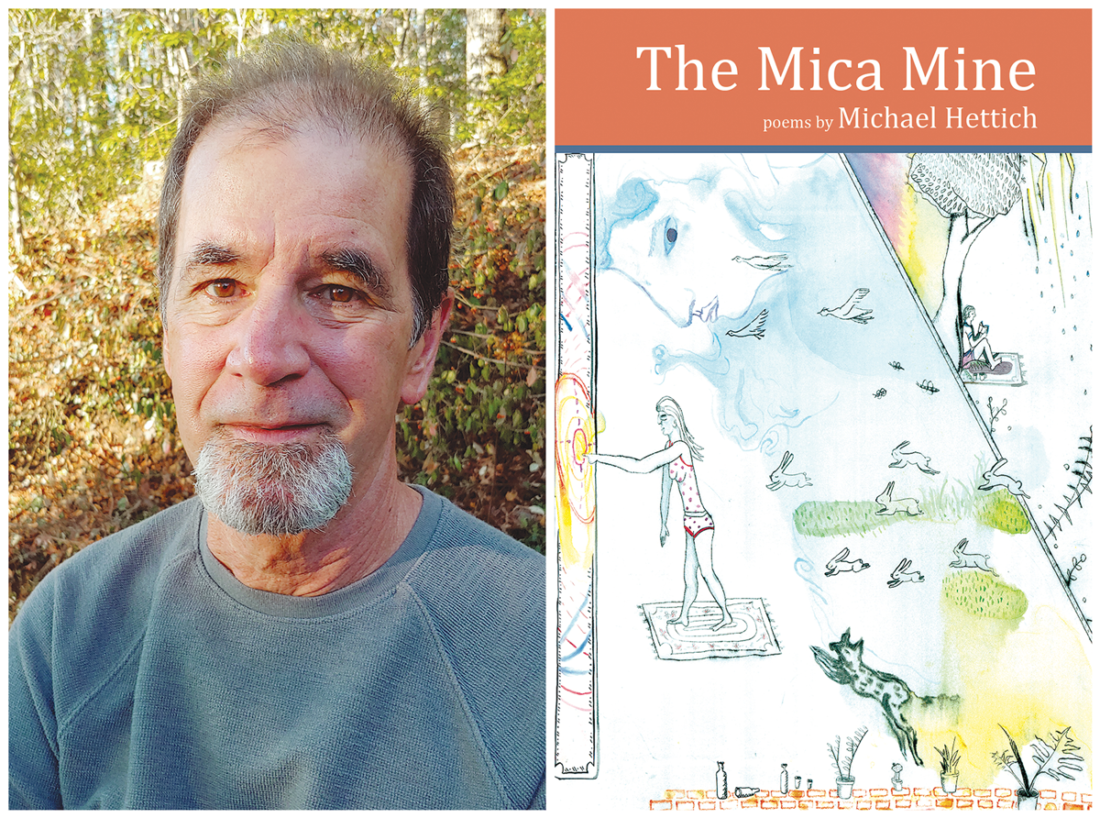

Originally from Brooklyn, Hettich holds a doctorate in English and American literature from the University of Miami. For 28 years, he served as professor of English at Miami Dade College. In 2018, Hettich retired; he and his wife, Colleen, relocated to Black Mountain shortly thereafter.

In this month’s poetry feature, we speak with Hettich about the way poetry connects readers to the living and the dead, the art form’s ability to capture the unsayable and the influential and metaphorical power nature plays in his work. Along with the conversation is Hettich’s poem, “The Distant Waterfall,” from his 2021 collection, The Mica Mine.

The Distant Waterfall

The big bear appears at your living room window

so close you can study his pigeon-toed walk,

his delicate steps around the potted plants

on your back wall. He sniffs at the base of the dogwood

where you dump your morning coffee grinds; you watch him

cock his ears when he hears you, naked

behind the sliding glass door.

Now he moves up the slope across the garden, pausing

to sniff new flowers and slurp a quick drink

from the bird bath—he doesn’t knock it over—then down

to the carport outside the garage where you stand now,

still naked, to watch him. There’s a big bag of garbage

on the floor beside you: mussel shells and fish bones,

so you thump on the door and growl like the fearsome

old man you’ve suddenly become,

and he seems to believe you, turns away and saunters

up into the woods, back up into the mountains

just starting to green with spring, where you wandered

yesterday looking for the waterfall whose roar

you thought you could hear in the distance but never

seemed to get closer to, no matter how you bushwhacked

and listened, then bushwhacked again—until you realized

it was probably just the ringing in your ears or the distant

highway, or simply the beautiful place

you’ve imagined finding for yourself and your family

to visit and be happy, and you’d pretty soon be lost

if you kept on looking deeper, moving further off the trail.

Xpress: What inspired this particular poem?

Hettich: Unlike most of the poems I write, this one was sparked — literally — by the occasion it recounts: I woke up one morning to see a big bear sauntering along just outside our kitchen window, like a dream that lingered in my just-awakened mind. Exactly as the poem recounts, I stood watching him, impressed by a kind of gentleness in his demeanor, then remembered the pungent bag of garbage in our garage, so I ran out there in my scrawny naked human body to scare him away. It worked!

Up to this point, the poem faithfully documents my experience. It’s here — at this “turn” — that the poem takes off and becomes interesting to me, as it moves from literal documentation into something more nuanced, complicated and ultimately unsayable by any form other than poetry.

I do, in fact, wander widely through the woods surrounding our house, looking not so much for a literal waterfall as for something brimming with the kind of energy and magic — and awe — a waterfall brings to any landscape. So, the waterfall is a trope — a metaphor for something we intuit but never seem to be able to actually come face to face with, some beautiful place where full happiness might be possible. We’re always straining to hear, or to feel, such a place, and of course we never get there. In fact, as the last lines tell us, such a quest can be a dangerous one, ending up in our being totally lost.

The poem itself was discovered in the vision of that bear, as I let myself follow its cadences and images toward the conclusion it reached. That’s part of why I trust it as a poem.

I’d love to hear more of your thoughts on poetry as a vessel for conveying the unsayable.

I think one of the primary functions of poetry — indeed of any art — is to communicate glimpses into what’s ultimately beyond our ken, that place of need and yearning where the mysteries reside. Of course — again — we never get there, except perhaps in those moments that resist paraphrase but make perfect sense. Such moments move us deeply, I think, because they fulfill a primal human need, not to find answers to unanswerable questions but instead to validate — and dramatize — our yearning to communicate fully with each other and ourselves.

In my own practice of poetry, I try as much as possible to focus my attention on cadence and rhythm, listening carefully to that cadence as I move forward, focusing my attention on the breath and the heartbeat of the poem while letting its images and narrative (if there is one) take my language forward. When this works — that is, when I’m able to forget myself in the process and simply follow the song — I trust the poem, trust its organic unity and truth. It’s a way of thinking beyond myself, in collaboration with my body — and with the great tradition of poetry that’s preceded me as well.

So, the formal practice of poetry as I see it has to do with centering on the breath, the heartbeat and the movement of our bodies as we walk. When we fully enter these processes, we can sometimes move beyond “thinking” into a place of intuition and the unsayable. In this sense, poetry might be thought of as “captured breath,” just as breath itself might be a figure for the spirit or soul.

And here’s something I find wonderful and inspiring: To really read a poem — any poem — we must breathe with the breath of the author of that poem, taking in the mystery of the unsayable urgencies that pricked that poet’s yearning — often hundreds of years ago — and still prick our own human yearnings today.

This notion of a deep connection across centuries — is that concept something you felt early on as a poet or did that reveal itself to you gradually?

I find one of the most inspiring aspects of writing poetry, for me, lies in the visceral sense that I’m participating in perhaps the oldest “art form” known to humans, certainly as old as cave paintings or dance. It’s an unbroken thread of breath running back at least 50,000 years.

My goal as a poet is to carry that fire forward a little bit, to pass it on somehow intact to those who will sing beyond me. That, to my mind, is more invigorating and inspiring than the hope — fantasy, really — of any real recognition of me as an individual poet, beyond my small time here on Earth.

And that realization opens up into all sorts of other wonderful realizations having to do with human culture as well as with our connections to other living creatures — all those other breathing entities — that surround us. It’s a kind of caring about the larger spirit of things — articulated in the breath of poetry — rather than in the mere self, this temporary manifestation of the breath. Which doesn’t mean I’m not hungry for whatever recognition comes my way.

To finally answer your actual question: I think from the beginning I had a sense — in the poets I loved most — of something larger than the merely personal and that this “breath embodied” was what moved me most in any poem. I have too many influences to list here. Certainly [Ralph Waldo] Emerson’s essays played a formative role for me. However, I think the moment of true revelation came when I was introduced to the well-translated Native American poetry collected in A. Grove Day’s The Sky Clears and John Bierhorst’s Four Masterworks of American Indian Literature. This was around 1978. The poems and commentary in these books just opened my mind and heart in ways that resonate still.

Is there a recent local poetry collection that excites you? If so, what draws you to the work?

Merrill Gilfillan is a poet, essayist and fiction writer who lived for a long time in Boulder, Colo., and now lives in Asheville. Though not technically “poetry,” the writing in his story collection, Talk Across Water, which was published by Flood Editions in 2019, is so beautifully nuanced and modulated, so full of incisive imagery and deft phrasing, that it sang to me as the best poetry does. And it continues to sing each time I dip in. Some of the stories are very short — short enough, in fact, to feel like prose poems. I’m with [poet] Jim Harrison, who said: “If anyone writes better prose in America, I am unaware of it.” [Gilfillan] deserves to be better known.

Lastly, who are the four poets on your Mount Rushmore?

I’ll list the poets who published most of their work after 1950 and have most influenced my own life and work. I want to emphasize, though, that I’m not at all suggesting that these are “the best” of their time, just that reading them changed my life and work most significantly. Ask me tomorrow, and I may have a different answer. Today they are: Gary Snyder, W.S. Merwin, Czesław Miłosz and Linda Gregg — with Pablo Neruda doing the carving.

As a poet and writer, I found your words (both of you) the article and the poem, so very interesting and beautiful. I’m not at all sure who has influenced me a lot but do love to write and read poetry… I write a lot of Inspirational Christian poetry and nature poetry. That being said, your bear poem was so wonderful. I’ll do my best to read you both more in the future. Thank you for this interesting and well written read. I enjoyed it a lot. – Regina McIntosh, Burnsville, NC

Thank you for the kind words, Regina.