“We need not say that Asheville suffers materially from the smoke nuisance,” The Asheville Citizen declared in a Jan. 6, 1916, editorial. “The thick black clouds of soot-laden smoke that roll over the city hour after hour, day after day, week after week and month after month call with greater eloquence for remedial measures than tongue or printed word can convey.”

One month later — following several years of discussion — A.H. Vanderhoof was named the city’s first smoke inspector. Shortly after his appointment, the ambitious monitor toured a number of cities, including Chicago and Cincinnati, to study their individual approaches to abating smoke.

By May, he presented a report with a proposed smoke ordinance to city commissioners. “The railway locomotive smoke is of tremendous volume,” the findings stated. The use of soft coal and improper furnaces and heating plants were also responsible “for a large measure of the smoke which hangs over Asheville.”

The push for the passage of a smoke ordinance continued into the following month. The proposal called on the installation of new smokeless heating plants, proper burning techniques and the installation of an unidentified apparatus for all 155 locomotives operating in Asheville (at a cost of roughly $75 per train — or $1,854 in today’s currency).

If such steps were implemented, Vanderhoof told city leaders, the smoke nuisance would disappear within three years.

On June 11, the commissioners approved the ordinance. Passage required “the appointment of a competent engineer to study conditions and make recommendations to the different heating and power plants of the city.” Once recommendations were made, owners would be given one year to comply.

Momentum, however, waned as America entered the Great War in April 1917. Among those called to duty was smoke inspector Vanderhoof, who joined the navy that month.

“While much gratifying progress was made just before the war began in eliminating the bituminous pall which used to hang over the city, there are still a hundred or more stacks in the heart of the city which in winter make Asheville resemble Pittsburgh as mist resembles rain,” The Asheville Citizen declared in its June 12, 1919, edition.

The article went on to declare, “If the city means to cope effectually with this smoke evil, all the houses and establishments in the congested district must either install the smokeless boilers, burn coke or hard coal or there must be a central heating plant.”

Yet subsequent reporting suggests the city took no actions to remedy the air pollution. On Dec. 19, 1920, another editorial lamented the absence of progress on the matter, noting “activities [to reduce smoke] have not been definitely resumed since the armistice.”

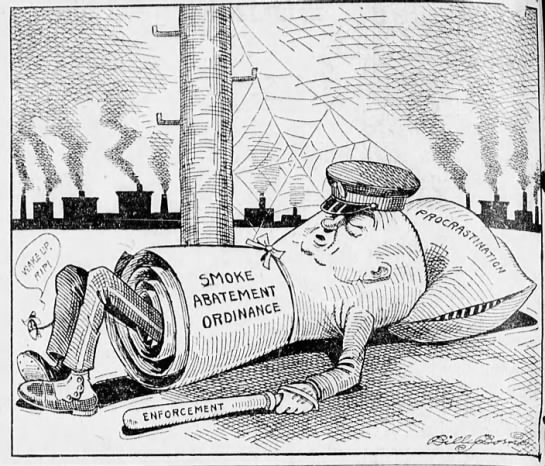

These same cries continued on and off for the next two years. An Aug. 12, 1922, editorial lampooned the city for dragging its feet on the issue, writing:

“Because the city has failed for the past few years to employ an inspector, and since little to no effort has been made to enforce the existing ordinance, a good beginning on the abatement of smoke has been virtually nullified and today some of the smokeless furnaces, with joyful abandon, paint the landscape black, causing residents and visitors alike to see red.”

Nearly a year later, on July 10, 1923, John Robert Stephenson was hired as the city’s second smoke inspector. With his appointment came a new confidence in the possibility of tackling the issue.

“The clouds begin to lift — the smoke clouds,” The Asheville Citizen wrote on Oct. 15, 1923. The editorial went on to state:

“Mr. Stephenson is holding conferences with managers of laundries and other establishments, whose business calls for huge smokestacks and large consumption of soft coal, and he believes that much good will be accomplished by teaching firemen not to overload the furnaces or otherwise practice improper firing. In this direction hope is discernible.”

But subsequent coverage on the matter is scarce. And within a year, Stephenson, who was 78, died. Following his death, similar complaints about the city’s smoke nuisance surfaced in the paper, along with similar proposed solutions — namely, the hiring of a smoke inspector to enforce established rules.

By December 1925, A.C. Sigmon was named to the post. But his achievements aren’t well documented. Several others held variations of the title until 1940, when the city raised the white flag to the black smoke.

“Asheville’s long fight against the smoke nuisance apparently was all but abandoned yesterday when city council, in adopting the 1940-41 operating budget, eliminated funds for the office of smoke inspector,” The Asheville Citizen reported on Aug. 2, 1940.

The report went on to note that the duties would be transferred to the office of the city engineer, “where permits for installation of stokers and heating plants will continue to be issued.”

The article concluded with a quote from Harvey N. Miller, the penultimate smoke abatement engineer to serve the city.

“It’s a big job,” Miller told the paper. “And the lay public didn’t seem to understand exactly the nature of my duties. I found most discouraging, however, indifference and non-cooperation on the part of city officials, the city school board, the churches and other leaders.”

Editor’s note: Peculiarities of spelling and punctuation are preserved from the original documents.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.