photo by Jodi Ford

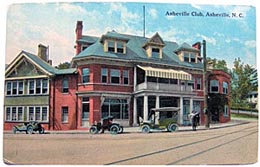

Extreme makeover: The Miles Building, above, has sheltered scores of Asheville shops and businesses from the 1920s through today. But in a previous life, it was the headquarters of the elite social organization, the Asheville Club, as the old postcard below shows.

postcard courtesy of Elwood Miles

|

There’s a bullet in the ceiling of Mountain Xpress Publisher Jeff Fobes‘ office, but it wasn’t deposited there by the disgruntled subject of some long-forgotten expose. And though the paper has been headquartered here since its founding, the heroic tale behind that slug is older still. For more than a century, in fact, the ornate brick-and-porcelain Miles Building — which anchors a key downtown intersection, fronting on Haywood Street, College Street, Battery Park Avenue and Wall Street — has seen more colorful Asheville characters playing out their dramas on its checkered-tile floors than Julia Wolfe’s boarding house.

After three generations of Miles family ownership, however, this gentleman’s club turned office building was sold July 8. But thanks to a quieter act of courage by longtime landlord Elwood Miles, that historic bullet isn’t going anywhere — and neither is Xpress. The Asheville native fended off aggressive, high-dollar-condo developers till he found a local couple who couldn’t offer quite as much cash but who promised to preserve this landmark’s heritage — and small-business tenants.

Asheville clubhouse

One look at the historic structure’s luxuriously wide hallways tells you it didn’t begin its long life as an office building. They should be much narrower, notes Miles; all that public space represents unprofitable square footage that can’t be rented out, he adds in his characteristically ironic tone. And indeed, before his grandfather bought and remodeled it for commercial use, what’s now the Miles Building was the headquarters of a social club that was the toast of Asheville’s Gilded Age.

In 1901, the 20-year-old Asheville Club decided to build itself an impressive new home on land owned by one of its members, Tench Francis Coxe, at the corner of Haywood Street and “Government Street” (now College Street), according to old newspaper articles preserved in Pack Library. Back then, the building looked much different: Contemporary images show a mansionlike exterior with stately columns flanking a main entrance on Haywood. Inside, according to a surviving account, oak-beamed ceilings and paneled walls lined with plaques and drinking steins enclosed reading, smoking and dining rooms furnished with dark-leather lounging chairs. Six bedrooms on the top floor provided sleeping space for the social club’s male-only members who, in those dirt-road days, could presumably blame bad weather for their inability to return home to their wives before nightfall.

The Asheville Club’s membership rolls were filled with the prominent names that still adorn buildings and streets all over town — Grove, Carrier, Coxe, Rankin, Sluder, Hilliard, Rumbough. The man remembered as the club’s “presiding genius” during its years on Haywood, however, was Dr. S. Westray Battle, a famed tuberculosis surgeon whose office and operating room were on the ground floor of the club building — about where Enviro Depot is today. (The Battle House — known for years as the haunted headquarters of WLOS-TV but now owned by the Grove Park Inn — is the mansion he built just before he died in 1927, according to Haunted Asheville by Joshua Warren.)

Wearing a cape, the courtly Dr. Battle would stroll the city’s wooden sidewalks with a cane in one hand and a bouquet of flowers in the other — one of which he would present with a bow to each lady he met, regardless of her social station. What truly won the good doctor a warm place in the town’s heart, however, was the applejack he brewed up according to his personal recipe for the club’s popular annual feast. He would serve it himself to each eager guest from a crystal punch bowl in the club’s billiard room — which appears to have been right where Asheville Brewing Supply does a thriving business today. (After multiple moves, the old gentlemen’s club closed its doors forever in 1934.)

Three generations, one desk

It was Herbert Delahaye Miles who transformed the building from a dignified but rather conventional structure into a unique artifact of Asheville’s architectural heyday, the Roaring ’20s. He was a vice president of Armour & Co. meatpackers in Chicago when his wife contracted tuberculosis. The doctors prescribed a standard treatment for TB: Move to the famously pure air of either Arizona or Asheville. Miles chose Asheville.

In order to have an occupation here, Herbert bought the building in 1919 from the Coxe estate, which owned the whole block fronting College Street. But Miles soon set about converting his new property into office space. A 1922 photograph shows that he’d already added the striking Italianate exterior on the lower floors that turned the building into a red-brick devil’s food cake layered with white terra-cotta frosting. The makeover was completed by the late 1920s, and the exterior has remained essentially unchanged ever since.

It’s not your ordinary office-building architecture, but then Herbert Miles was not your ordinary retired corporate executive. In 1948, at the age of 81, he made his debut as a published poet with Look Up, O World, a book of poems on topics ranging from the ambivalent birth of the Atomic Age to the spiritual wisdom of the local mountain folks. The late-blooming bard must have had a way with words; in 1933, at the height of the Depression, he’d made a special trip back to Chicago by train and persuaded the bankers who held the mortgage not to foreclose on the building.

Herbert Miles was also a charter member of the Asheville Civitan Club; active since 1923, the service organization has counted a Miles as a member more or less continuously.

Herbert’s son, Holbert Delahaye, joined him as assistant manager in 1937. Elwood, born five years later, remembers playing in the office as a child while his father and grandfather worked at the same double-sided desk — the latter treating the boy now and then to a snack from a jar of pepitas (shelled pumpkin seeds) he kept there. When Herbert passed away in 1958, Holbert moved to his father’s side of the desk; and when Elwood joined the family business in 1971, he took the side Holbert had vacated. In the 1990s, when Holbert grew too elderly to come in anymore, Elwood moved around to the father’s side; but having no children of his own, he continued to use the son’s side for handling the business of the family trust to which his grandfather’s will had bequeathed the building.

All in all, it’s a living museum; even the hallway decor has been passed down intact through several generations. Its unusual mustard-and-silver color scheme — which still survives as of this writing — dates to the 1920s. In the ’50s, Holbert Miles had Bill Williams, the son of the original painter, reapply the paint in the same colors and patterns. In the ’80s, Williams returned with his daughter Billie to touch it up; and earlier this year, Elwood had Billie come back and freshen up the paint once again.

Smoke of ages

But those walls weren’t easy to keep clean back when everyone in Asheville burned coal to stay warm. Holbert had to hire a man to wash the black grime off the walls once a year, Elwood recalls.

“My dad told me that the city, in those days, kept an inspector in the top of the Jackson Building [then the city’s tallest structure] in the mornings with a pair of binoculars,” he continues, “and he would keep an eye on chimneys smoking. He had a stopwatch, and any chimney that smoked heavily when the furnace was first starting up in the morning for more than five minutes, the city would send them a citation and tell them to ‘get your furnace adjusted.'”

That inspector would most likely have worked for Asheville’s Smoke Abatement Agency as a member of the “Dawn Patrol.” According to a 1952 newspaper report, this crew conducted early morning inspections of boiler rooms to ensure that they were being fired up properly. The SAA, established in the 1940s to control coal-smoke pollution, was the direct ancestor of today’s smog-regulating Western North Carolina Regional Air Quality Agency.

The Miles Building switched from coal to natural gas in 1968, but there’s still a thick layer of black coal dust coating the roof beams in the attic. To this day, Xpress employees sometimes clamber through that dark, labyrinthine space helping Technologies Manager Michael Ropicki run new phone and computer lines — and come back down black as chimney sweeps.

Another constant chore in those days, notes Miles, was cleaning tobacco smoke off the walls. It probably didn’t help that Fater’s Cigar Store was a longtime fixture in part of what’s now Karmasonics; the store had a lunch counter served by a kitchen in the Miles Building’s basement, connected by a dumbwaiter whose remains can still be seen. Many of Fater’s customers could no doubt be found lounging, smoking and reading newspapers in the Asheville Downtown Club; no relation to the old Asheville Club, it occupied a large suite on the first floor for decades.

Reporters laboring in the building late at night have sometimes wondered whether the scent of cigar smoke wafting up the broad stairs was coming from the ghosts of those fashionable gents. In fact, the culprit turns out to be a real, live lover of stogies — but other, creepier apparitions have indeed put in an appearance here.

The haunted office

Few old Southern Appalachian structures seem to come without a resident haint or two — and the Miles Building is no exception. At least twice in the paper’s 11-plus years on the premises, Mountain Xpress employees have been startled by ghostly phenomena. Both visitations took place in Room 212-213; now home to the paper’s Production Department, the two-room suite sits right next door to the Miles’ office.

When Ropicki joined Xpress in 1999, he and the production manager both had desks in the front room. “It was right about lunchtime,” Ropicki recalls. “One or the other of us had just bought lunch and brought it back and had laid a sandwich out on the desk. At exactly the same time, she and I both saw out of the corner of our eye a man’s hand with a white-cuffed shirt sleeve reaching across the desk toward that sandwich. And we both looked back, thinking that it was [someone] playing some kind of a joke — but there was no one there.”

Arts & Entertainment Editor Melanie McGee, meanwhile, tells of having been in the front room at times “when I know that there’s nobody in the other one — early in the morning or later at night. And sometimes I can hear the creak and the swivel of the chair in the back room. It’s like the sound that a swivel chair makes when somebody gets up off of it. You know, like a metallic ‘squeak-squonk’ — I’ve heard that several times,” she says.

For his part, Elwood says he’s never experienced a ghost.

Shoot ’em up

The haunted suite was also the scene of the crime that accounted for the bullet still lodged somewhere under a layer of plaster in the publisher’s office down the hall. It was sometime in the early 1980s, and those rooms were then being rented by United Food & Commercial Workers International Union Local 525 — the meat-packers’ union, which was influential in grocery stores around the Southeast. But what happened in Room 212-213 that day had nothing to do with labor strife.

Otis Ware had a photography studio on the opposite side of the Miles’ office from Room 212-213. One evening, he and his secretary were working late, and so was a female employee of the union. All at once, “I happened to hear [the union woman] screaming,” Ware recounts. “[I] rushed out to see what happened, and some guy had forced himself in on her and tried to take advantage of her.”

Ware ran back to his office and grabbed a pistol from his desk drawer. Meanwhile, the attacker fled down the hall and started climbing out the window onto a ledge.

Ware’s secretary, he remembers, “ran outside, and hollered back to tell me, ‘Yeah, he’s coming out of one of the windows!’ Well, I ran outside and shot him back inside,” firing from in front of what’s now the Haywood Park Hotel. “I wasn’t trying to hit the guy but kept him pinned down, and then I told her to go call the police. I finally got him cornered [under a table in the hallway] and pinned him down till they got there.”

Ware received a commendation from the mayor for his heroism. But he also caught some ribbing from the cops for what he’d done to his landlord’s property.

“Now that I think about it, it’s kind of funny. I knew the policemen that worked that downtown beat, knew all of them, so they used to pick with me about shooting up the man’s place!”

Ware, a longtime leader of Asheville’s black community, is now the Rev. Ware: He founded the Solid Rock Missionary Baptist Church six years ago in another historic building on Wyoming Road. And back in the ’70s, Ware led Bite, Chew and Spit — the house band for the Orange Peel, then the largest venue for black music in Asheville and a thriving center for African-American culture (see “Slice of Life,” Oct. 23, 2002 Xpress).

At that time, Ware was also closely involved with another pioneering local institution promoting racial equality — WBMU-FM, one of the first black-operated radio stations in the country — which broadcast from the Miles Building, in an office just below Ware’s photography studio.

Xpress personals really work

Married at age 47, the now 63-year-old Elwood Miles and his wife, Margaret, have no children, and none of his nephews or nieces expressed any interest in taking over the building. His grandfather’s trust specified that the building had to be sold when Herbert’s last remaining offspring died; that happened when Elwood’s Aunt Marjorie passed away in July 2003.

“My father and I always assumed … that I would buy the building from the other beneficiaries and continue to operate it as the sole owner,” says Elwood. “But we didn’t plan on his sister living to be … almost 102!”

Instead, Elwood decided to sell the building, retire and pursue his many hobbies (which range from motorcycling to ham radio) full time. He wasn’t quite prepared, however, for the throng that was waiting to pounce on the prime downtown location.

“We put it out on our national Web site Wednesday evening,” says Kenny Jackson of Whitney Commercial Real Estate, a specialist in downtown Asheville properties who worked with Miles on the sale. “And by Thursday noon I think we already had three or four written offers — a total of 12 within a week. It was one of those properties that had been on people’s list — you know, ‘If this thing ever becomes available, I want a shot at it.’ It hadn’t been on the market in over 90 years.”

But a lot of those offers came from out-of-state investors who wanted to convert the Miles Building’s offices into pricey condos.

A lot of people are moving here from big cities to retire or raise a family, Jackson explains, “and you just have a lot of [buyers with] money who are wanting to live downtown” — often in a second home where they may spend just a weekend or two a year.

“It’s kind of like a Charleston, South Carolina, or a Richmond, Virginia,” he continues. “Condos — right now they make the most profit for people. But you get to a point to where, OK, is there going to be too much of it? … What’s important to those of us who live here is that we don’t want to lose what [Asheville] is.”

Besides, converting the building to condos would have meant evicting all the office tenants and tearing out all the history — or perhaps even consigning the historic structure to the wrecking ball (as happened to the former Penney’s building just a few doors away). Especially galling to Miles was the patronizing attitude some of those potential buyers showed toward his concerns about preserving his heritage. “We understand how important your daddy’s building is to you,” one person practically sneered over the phone.

But just as Elwood was about to give up on what was beginning to seem a hopelessly old-fashioned ideal, he got an offer from Stephen and Mary Ann West, a newly wedded couple living practically across the street.

The two had separately fallen in love with Asheville and moved here at the same time from different places. One of the first things Mary Ann did after moving in was place a personal ad in Mountain Xpress — and one of the first things Stephen did was read it.

“I ran an ad, and it was the only one I ever ran, and he answered it — and he said it was the only one he ever answered,” remembers Mary Ann. “We met for coffee at Old Europe,” and after a yearlong romance, they married last November.

Looking to make an investment in the town they both loved, they were told about the Miles Building. Two days later, on Mother’s Day, they made an offer. Their bid wasn’t the highest — but luckily for them, money wasn’t Miles’ main concern.

“I think he was more focused on what was [a buyer’s] intended use than how much are you willing to pay,” says Jackson.

“Elwood called and interviewed me for about 30 minutes on the phone and asked me what I thought about the building and what my intentions were,” recalls Mary Ann. “Then he called [Stephen] and interviewed him. I told him it’s like having Donald Trump interview you for The Apprentice. … I told other people it was like waiting for the papal smoke to rise [which was happening] at the same time. And I’m looking at the roof of the Miles Building, wondering, is there any white smoke coming out of there?”

The Wests made no secret of their plans for the Miles Building — to leave everything exactly as it is. Well, almost exactly. The cast-iron scrollwork would get a cleaning, the bathrooms would be remodeled, awnings would be installed on the outside and central air conditioning on the inside.

“We intend to make it a first-class building — the prettiest, best, most wanted building in town,” Mary Ann told Xpress, adding that she and Stephen were looking forward to being “landlords to our Cupid.”

“After talking with the Wests, I think we all knew … that they were the right people,” says Jackson. “It’s almost like they said the exact things that he needed to hear. You could tell they were very genuine. They loved the building — they just wanted to restore it, keep it as being one of the key fixtures in downtown Asheville, and really just kind of preserve it. That’s exactly what he wanted.

“What this [deal] proves is that it can be done. You don’t have to turn it into condos, you don’t have to just make the biggest buck. I think the Wests are really going to do the right thing, and I think that could be a great blueprint to show other people.”

“We feel as though the Miles Building has been entrusted to us,” says Mary Ann.

Miles sold the Wests his family’s building for about $2 million, Jackson confirmed. But in between the handshake and the signature, there was one last sticking point: that mustard-and-silver color scheme.

“[Elwood] doesn’t want me to change the paint on the inside, but I feel as though that paint is really dingy,” Mary Ann insists. “And so he said, ‘Well, my grandfather chose that paint.’ And I said, ‘Well, your grandmother wasn’t there when he chose it — she was out of the room!'”

All the same, Elwood Miles feels he’s fulfilled his obligation to his heritage, and he’s as ready as he can be to move on.

“My father always said of people in the building that ‘no one stays here forever.’ He said, ‘Some may stay six months, and others may stay 20 years, but nobody stays forever.’ That has applied to his father, and it has applied to him, and it is about to apply to me. But I have done the best I can to get it into good hands for the future, and I hope I have been successful.”

[Freelance writer Steve Rasmussen is based in Asheville.]

I opened my first law office in the Miles building in 1972 and was there several years before moving to California to practice. I remember Mr. Miles and Elwood and have very fond memories of my time in the Miles Building.