By Sally Kestin and John Boyle, Asheville Watchdog

Asheville’s water may be restored, but the spigot of information from city officials is still clogged.

Last week, as the public clamored for detail on the holiday outage that left as many as 38,500 customers without water and likely cost businesses millions of dollars in lost revenues, the city held private meetings with City Council members and did not make the staffers closest to the water outage, City Manager Debra Campbell and Water Department Director David Melton, available for interviews.

City staff compiled a timeline of the water outages but did not respond to Asheville Watchdog’s repeated requests to provide it.

City Council members received their first detailed briefings Jan. 5 in a series of “check-in” meetings with staff — meetings that appear to be specifically arranged to avoid being open to public scrutiny. Check-ins are held with no more than two Council members and the mayor per session — not enough to constitute a quorum, which under state law would then require a public meeting.

The agenda for Thursday’s three check-in sessions included a “timeline of events” of the water outage. Campbell and Melton were on hand to provide information and answer questions.

“This isn’t a public meeting,” city spokeswoman Kim Miller told Asheville Watchdog. “No check-in meeting contains a quorum of Council members, and we do not provide third-party access to the meetings.”

City Attorney Brad Branham said check-ins, which have been going on for at least four years, are legal and give Council members an opportunity to ask questions, speak freely and “ensure that they are updated on any kind of critical matters going on.”

“There’s never a vote taken; there’s never an action decided,” Branham said. “They’re authorized to gather in small groups and talk.”

“Keeping public in the dark”

Hugh Stevens, general counsel emeritus of the N.C. Press Association, said the meetings appeared designed to circumvent the open meetings law.

“It’s certainly a shabby, and in my view, completely underhanded process that has the purpose of keeping the public in the dark and allowing these folks to have discussions among themselves outside of public view,” Stevens said. “What the meetings law says is that every official meeting of a public body shall be open to the public and any person is entitled to attend.”

Council members Kim Roney and Sage Turner told Asheville Watchdog that for a crisis as big as the water outage, the city needs to be completely open and transparent.

“I believe we need to be having this level of conversation in public,” Roney said.

“The check-ins in general are helpful in many ways across other items,” Turner said. “The severity of this issue likely warranted an emergency meeting or a special meeting of Council … with Council present, media present and residents present, if they wanted.”

Timeline not forthcoming

The city began issuing public water conservation advisories on Dec. 26, after the Mills River water plant failed the morning of Christmas Eve. Mayor Esther Manheimer said she was not alerted that the system was failing until Dec. 26.

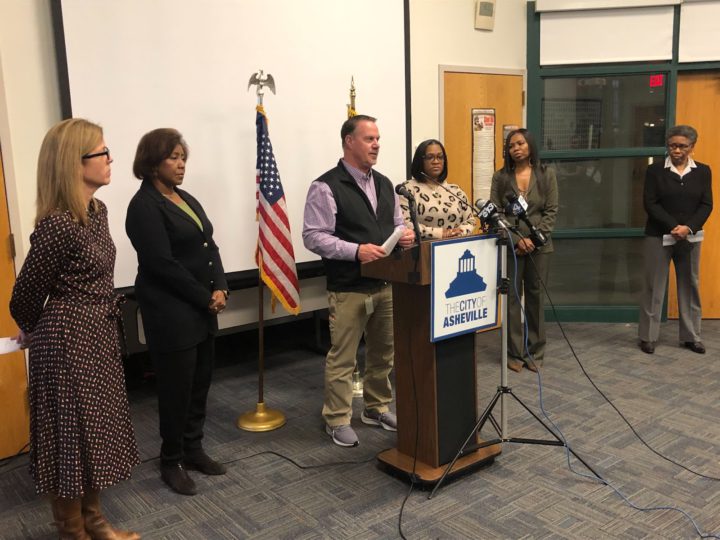

But the city did not hold its first press conference until Dec. 28. Subsequent press conferences were held Dec. 30, Dec. 31 and Jan. 3. Water was not restored in all areas until Jan. 4.

Asheville has a city manager form of government, meaning Campbell oversees nearly all hiring, operations and budgets. But the city’s elected mayor became the de facto public information officer during the crisis.

A lawyer by profession, Manheimer made no criticism of Campbell in a Jan. 4 interview in City Hall, although she did allow that the city failed in some aspects of its response to the outage, including communications.

“I felt like it was important to speak directly to the community,” Manheimer said, when asked if Campbell should have been front and center. “I mean, I feel like the elected officials and probably the mayor, most of all, are the ones the community will hold accountable for something like this. And that’s who they expect to speak with them.”

Manheimer noted Campbell had been at the press conferences. The mayor also said the city has a detailed chronology of the series of events that cascaded into most of the south end of the city’s water service area being without water.

“Our water staff has been keeping, they’ve been documenting every decision they’re making – everything they’ve done since the moment that started,” Manheimer said after a Jan. 3 press conference.

Branham, the city attorney, said Friday that the city had two documents that could be considered timelines; one he called “pretty highly technical” that included abbreviated locations. “No one would understand it if they weren’t working in the city of Asheville’s Water Department,” he said.

The document, he said, “contains a lot of information that’s actually restricted from public access because it deals with public infrastructure.”

“Somebody else was putting together a timeline for the purpose of communication, but it didn’t also include the water stuff,” he said. Branham said the two documents were being merged and were to be made public Jan. 9.

Asked to provide the documentation the city had as of Jan. 6, Branham said he did not “have it in hand” and that it resided with the city manager’s office. Campbell did not respond to email requests for the timelines over two days.

Hardships for residents, businesses

The full impact of the water outages has yet to be tallied. Council member Turner said the city heard from one South Asheville mother of three, who had the flu along with her children: “She said, ‘I have no water to bathe them to bring down temperatures,’” and her pediatrician’s office was closed due to lack of water.

Turner said apartment complexes lost heat because their heating systems ran on water. One 74-year-old woman told the city she had been without heat for three days and “all she had was a heating pad to keep her warm,” Turner said.

One business lost an estimated $50,000.

Eric Scheffer, who owns and operates two Vinnie’s Neighborhood Italian restaurants and Jettie Rae’s Oyster House, said Vinnie’s in South Asheville was closed for five days. The north location lost one day, Dec. 23, when the water went brown.

“The financial hit is, it’s quite extensive,” Scheffer said. “It’s well over $50,000.”

The week between Christmas and New Year’s is the busiest of the year, Scheffer said, noting that he worries more about his restaurant staff than himself. He has a “robust” loss-of-business insurance policy that will help but won’t cover lost income for servers and other workers.

“You know, it’s a tough time [to be closed]. You’re hoping to rake in the cash,” Scheffer said. “That’s usually a time that servers that are smart are putting money away, and a lot of them now are in pretty serious trouble trying to make rent. … These people live paycheck to paycheck, a lot of them.”

A server working that week could have made $1,500 to $1,800, Scheffer said.

An Asheville resident since 1995, Scheffer feels infrastructure in general has been ignored while the city prioritizes other initiatives.

“There’s always been a lack of vision when it comes to the growth that was coming,” Scheffer said. “We knew we were building a town that was going to be based around tourism, hotels, restaurants. And there was very, very little done to put money in [infrastructure]. It’s sad. It’s very, very sad.”

What happened?

Melton and Manheimer have provided some details of the water system failure at press conferences, and in Manheimer’s case, in individual interviews. But many questions remain.

Everyone agrees on this: The Asheville area saw a wicked winter freeze in the days leading up to Christmas and right after, and that led to numerous water line breaks, including “11 or 12” larger city lines, Melton has said.

According to the National Weather Service, Asheville Regional Airport, the city’s official weather station, saw average daily temperatures of 17-28 degrees below normal in the days preceding the outages:

- Dec. 23: The low temperature was 2 degrees Fahrenheit, and the high was 41.

- Dec. 24: The low was zero, the high 24.

- Dec. 25: The low was 12, the high 31.

- Dec. 26: The low was 12, the high was 34.

The bone-chilling front receded by Dec. 27. The low that day was 24 and the high 45, just 5 degrees below normal.

Manheimer and Melton have described the freeze and the simultaneous demand on water service as “unprecedented.” That’s not the case.

John Bates, a meteorologist who retired in 2018 from the federal government’s National Centers for Environmental Information in Asheville, said he analyzed hourly weather data from Asheville Regional Airport.

“There have been about seven, eight cold waves of equal or colder temperatures in the last 50 years of record,” Bates said. “The coldest being around Jan. 21, 1985, when the low reached minus 16 Fahrenheit. Cold waves are not rare.”

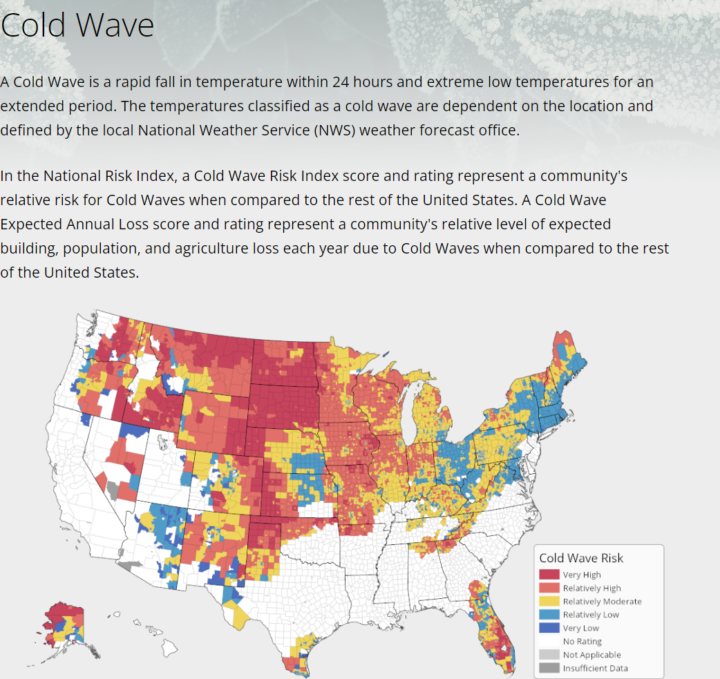

Bates also pointed to a Federal Emergency Management Agency “cold wave index that appears to indicate that we are in a relatively high/moderate risk for cold waves,” Bates said.

FEMA defines a cold wave as “a rapid fall in temperature within 24 hours and extreme low temperatures for an extended period.” These are dependent on the location. For instance, Florida is included in the map.

“I think the FEMA risk index is something the city should be paying attention to, more than my quick and dirty look,” Bates said.

Three sources of city water

At the height of the freeze, the Asheville water system was seeing unusually high demand, city officials said, putting out 28 million gallons a day, up from an average of 22 million gallons.

The city serves water customers from three sources: the North Fork Reservoir and treatment plant in the Black Mountain area, the Bee Tree Reservoir and plant near Swannanoa, and a water intake and treatment plant on the Mills River.

North Fork, with a capacity of 31 million gallons per day, is the workhorse, providing most of the water for the system, according to the city’s annual water quality report. Bee Tree’s capacity is 5 million gallons a day, and Mills River, 7 million.

After treatment, water travels through 1,702 miles of water lines and is stored in 35 reservoirs, according to the annual report. Each day, the system delivers water to over 156,000 people in Asheville, Buncombe County and Henderson County.

Sacrificing the south?

The Christmas outage stemmed from a combination of extremely high demand over the holiday, a severe freeze that caused city-owned and private lines to burst and the freeze-up of the Mills River plant’s intake system, Manheimer and Melton have said.

Manheimer, who started attending emergency water meetings Dec. 27, said her first notification that something was wrong came in the afternoon of Dec. 26. With all three facilities in operation, the city had been pumping out 28 million gallons a day over the holidays.

Water operators suspected leaks were occurring. The Mills River plant went offline, came back on, then went off again, Manheimer said.

“At some point, the decision was made to tie off the North Fork (facility) from the south, because once Mills River came back online, if you didn’t tie it off, the whole system would have to go under a (boil water) advisory,” Manheimer said. “So, the decision to tie off the South was to basically preserve the rest of the city, so the rest of the city with the hospital system, everything, would not have to go under a boil water advisory. The thinking there, as I understand it, was, ‘OK, we’re going to experience a loss in the south.’”

Manheimer said she doesn’t know exactly when the decision was made to “tie off” the south from the water coming from the North Fork. She said water officials believed the cutoff in water to southern customers would be temporary, though.

Alerts started going out Dec. 26 about water conservation because, Manheimer said, “they knew at that point they weren’t going to have enough pressure in the system to sustain continuous water coverage.”

Melton has said repeatedly that the age of the water system was not a factor in the breakdown.

“This was all weather-related,” he said at the city’s Dec. 30 late afternoon press conference.

Turner, the council member, said the city lost, “I think it was 29 large pipes that were over 6 inches. And that’s a large amount of water loss.”

She said pipes freezing below ground were out of the city’s control. “But within our control were items like making sure that the external equipment down at the Mills River had some kind of warmth around it. It’s not encased, I understand, there’s some kind of mechanism outside experiencing cold temperatures and allowing it to freeze.”

No problems at nearby water plant

Manheimer acknowledged the city is getting a lot of criticism about its handling of the event, and not paying enough attention — or funding — to the city’s water system. But she pointed out the water department is self-funding through its billing and has allocated $10 million a year in recent years for infrastructure improvements.

“I’m guessing that you may be able to get 10 people in a room and have a disagreement about that. You know, 10 different opinions,” Manheimer said.

Asheville resident Mike Rains is one of those with strong opinions about the city’s handling of the crisis. A retired engineer who worked for Duke Energy at a nuclear power plant, Rains lives on a street in North Asheville that has had recurring water line breaks.

Before the current crisis, Rains had a sit-down with Melton, receiving an overview of the system, and he has observed water work crews in action. In his career, he said, Duke Energy had to take a new approach to quality control and maintenance at its nuclear facility, and he believes the city’s Water Department needs a similar reassessment. Because of the changes in elevation that result in greatly increased pressures, Asheville’s system is much more complex than “flatland” systems, he said.

Rains said he finds many analogies between the nuclear plant he worked in and the city’s complex system. He said he hopes to be appointed to a committee the Asheville City Council plans to create at its Jan. 10 meeting to review the water system failure and report back with a detailed analysis and recommendations.

Citing previous breaks in city lines that resulted in outages, as well as mistakes made at the Mills River plant that resulted in a $1.6 million repair in 2021, Rains said the city has been late in adopting a “root-cause analysis” of its water woes.

In this event, Rains said, he suspects instrumentation froze up “because it wasn’t properly maintained.” Duke experienced similar freezes with instruments and water lines, he said.

While Rains conceded the cold likely was the main driver of the outage, he said he believes the Water Department needs a cultural overhaul, with an emphasis on better quality control and attention to detail to prevent spiraling mishaps.

“The reality is, you have to bring your organization up to a level where [mishaps] don’t happen,” Rains said.

Rains noted that the city of Hendersonville’s water system did not fail during the cold snap. Its water intake and treatment plant is within a mile of Asheville’s Mills River facility.

City of Hendersonville spokesperson Allison Justus checked with the city’s utilities director, noting that the two systems are “vastly different regarding infrastructure, facilities, processes, and the geography and elevations served.”

The Hendersonville plant serves 31,000 connections across Henderson County, typically treating 6.8 million to 7.2 million gallons of water a day for use by customers. On Christmas Eve, the plant treated 7.3 million gallons, and on Christmas Day 8.1 million.

Hendersonville had a line break along Asheville Highway (U.S. 25) affecting 80 customers but “no major issues over the holidays,” Justus said.

“Before predicted weather events, treatment plant staff checks to make sure generators and heating units are functioning properly,” Justus said. “Some precautions to prevent freezing are built into the plant, such as above-ground piping being wrapped and having heat tape.”

Communicate ‘early and often’

Asheville City Council member Maggie Ullman said the city needs more answers about how its three treatment plants “work together and how that works for distributing water.”

“We have dealt with situations multiple times in the past where Mills River was offline and North Fork and Bee Tree were able to handle producing and distributing water to the whole system,” Ullman said. “We should be prepared to serve substantial increases in demand.”

Ullman said the city needs to improve its communication with the public when outages occur.

“In times of emergency, the golden rule is early and often,” she said. “I think that folks in the face of not having water wanted to hear updates more frequently.”

Asheville Watchdog is a nonprofit news team producing stories that matter to Asheville and surrounding communities. Sally Kestin is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative reporter. Email skestin@avlwatchdog.org. John Boyle has been covering Western North Carolina since the 20th century. You can reach him at (828) 337-0941 or via email at jboyle@avlwatchdog.org.

City Council meeting today 5pm may be raucous !

Campbell is at least as incompetent as her predecessor Gary “don’t do anything and they can’t fire you” Jackson. No emergency plans. No contingency plans. Makes you wonder why nearby politicians forced Asheville to provide water to their constituents when they are so incompetent.