In February, my nephews and I decided to hike to the summit of Mount Mitchell. But the most interesting thing to happen that day turned out to be eating our organic-peanut-butter-and-black-currant-jelly sandwiches while perched atop the grave of Dr. Elisha Mitchell, the geologist for whom both the peak and the state park are named. No disrespect was intended (and I certainly hope Dr. Mitchell was/is not allergic to peanuts). The fact is, we had no idea we were sitting on a grave—or even who Dr. Mitchell was.

I’m new to the area, and my outdoorsy nephews were in town for the weekend. These guys can’t sit still, and they quickly convinced me that a winter hike to the highest peak east of the Mississippi would be the perfect way for Uncle Craig to start exploring the Western North Carolina outdoors.

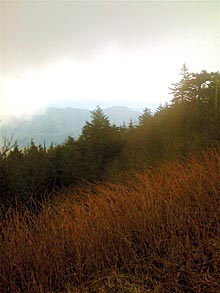

Next thing I knew, we’d dropped off the car at the park office, our sights set on a moderate five-mile hike to the summit and back. The air was cold and moist, the temperature about 30 degrees lower than in Asheville. Overhead, patches of blue sky battled an overwhelming force of menacing gray clouds. We pretty much knew the dark forces would win out, but we were ready for anything. Donning our hats, gloves and daypacks stocked with munchies and water, we headed up the Old Mitchell Trail.

We each had our idea of what the top would be like: the beauty and serenity of the Black Mountains, the glorious views on all sides, especially north toward Mount Craig. And the chance to have our picture taken next to the sign or plaque designating Mount Mitchell’s summit (6,684 feet) as the highest point east of the Mississippi.

But as we approached our first glorious North Carolina summit, we rounded a bend in the trail and found dark, hulking masses of concrete and rebar poking out of the misty mountaintop at the far end of a basketball-court-sized area strewn with stacks of lumber, metal beams, tractors, trucks, piles of dirt and litter. We couldn’t have conjured an image more in conflict with our summit expectations.

In February, my nephews and I decided to hike to the summit of Mount Mitchell. But the most interesting thing to happen that day turned out to be eating our organic-peanut-butter-and-black-currant-jelly sandwiches while perched atop the grave of Dr. Elisha Mitchell, the geologist for whom both the peak and the state park are named. No disrespect was intended (and I certainly hope Dr. Mitchell was/is not allergic to peanuts). The fact is, we had no idea we were sitting on a grave—or even who Dr. Mitchell was.

I’m new to the area, and my outdoorsy nephews were in town for the weekend. These guys can’t sit still, and they quickly convinced me that a winter hike to the highest peak east of the Mississippi would be the perfect way for Uncle Craig to start exploring the Western North Carolina outdoors.

Next thing I knew, we’d dropped off the car at the park office, our sights set on a moderate five-mile hike to the summit and back. The air was cold and moist, the temperature about 30 degrees lower than in Asheville. Overhead, patches of blue sky battled an overwhelming force of menacing gray clouds. We pretty much knew the dark forces would win out, but we were ready for anything. Donning our hats, gloves and daypacks stocked with munchies and water, we headed up the Old Mitchell Trail.

We each had our idea of what the top would be like: the beauty and serenity of the Black Mountains, the glorious views on all sides, especially north toward Mount Craig. And the chance to have our picture taken next to the sign or plaque designating Mount Mitchell’s summit (6,684 feet) as the highest point east of the Mississippi.

But as we approached our first glorious North Carolina summit, we rounded a bend in the trail and found dark, hulking masses of concrete and rebar poking out of the misty mountaintop at the far end of a basketball-court-sized area strewn with stacks of lumber, metal beams, tractors, trucks, piles of dirt and litter. We couldn’t have conjured an image more in conflict with our summit expectations.

On top of that, it was cold as hell. We tried to make the most of our time at the top by climbing onto the highest point of the half-completed concrete structure for a better view before settling down on what we thought was a random pile of I-beams to eat lunch. (Later we learned that it was actually a protective skeleton covering Mitchell’s grave.) And there wasn’t even a sign or marker for us to pose by for a photo!

A bit deflated but certainly not undone by the experience, I came away with a desire to learn more about the mountain’s history and the plans for its future.

Many readers probably already know that the mountain and state park are named after Dr. Elisha Mitchell, the UNC professor who used barometric-pressure readings and mathematical formulas to measure the height of this mountain during the 1830s and 1840s. On a trip to measure the peak again in 1857 in the midst of a dispute about its height, Mitchell fell to his death.

So much for history. But what about the jumble of construction materials on top?

First off, the summit is currently closed to all foot traffic, according to Park Superintendent Jack Bradley—meaning my nephews and I shouldn’t even have been up there. And construction of the new observation platform began in September 2006. Yikes!

Finally, while Bradley said he expects the platform and trail to be completed this July, he suggested that I contact Vaughn & Melton, the company overseeing the project, for a more accurate schedule.

Hardy Willis, the project leader at Vaughn & Melton, shed additional light on the observation platform’s status. The goal was to reference the previous tower by using a stone veneer and retaining a turretlike shape. But by making the new structure an open, circular platform instead of an enclosed tower, visitors will have true 360-degree views.

Another key component is the fact that the new platform will feature an entry ramp that meets Americans with Disabilities Act standards for wheelchair access. And a new trail from the parking lot to the summit will be made of stamped asphalt, satisfying ADA requirements while achieving a more natural integration with the environment.

The original bronze disk that marked the summit will be replaced with an 11-foot inlaid granite map of the state of North Carolina, framing a smaller bronze summit marker.

But the biggest question, of course, is when will the summit reopen? Originally slated to be wrapped up last fall, the project encountered some construction issues, said Willis.

The company’s Web site (www.vaughnmelton.com) features a computer rendering of the future structure and loads of photos. And while a digital “construction status” meter at the site shows the project being only 30 percent complete, Willis says he expects that work will resume this month, and the new platform and trail completed by August.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.