Is Mahler (1974) the best of Ken Russell’s composer biographies? I’m inclined to say yes. But even if it isn’t, it’s undoubtedly one of the finest films ever made on the life of a composer—or indeed any artist. When the film was run a few years ago by the Hendersonville Film Society, it divided the audience into two distinct camps—those who wanted to see more Ken Russell films and those who wanted to walk out on this one. It’s that kind of film, and Russell’s that kind of filmmaker, which, of course, is partly why he’s one of the greats. Mahler is from Russell’s richest period of filmmaking and is the start of what, for me, are his three greatest works: this, Tommy and Lisztomania (the latter two both from 1975). The three films form a kind of stylistic trilogy that push the boundaries of filmmaking to a degree that has rarely been equaled and never been topped.

Made for very little money—about $320,000—Mahler is one of those rare chances to see a filmmaker at work without a net. A professionally created film meant for theatrical release made for that amount of money (roughly half the cost of an hour-long U.S. TV show from the same era) is pretty much a do-it-yourself affair. Ironically, it would go on to win the Best Technical Achievement award at Cannes. Money isn’t everything.

The film is a deceptive work that looks at once complex and simple. On the one hand, it is very simple indeed. Gustav Mahler (Robert Powell) and his wife Alma (Georgina Hale) are on a train that is taking them back to Austria, following Mahler’s stint as conductor of the New York Philharmonic. Their marriage is not in good shape, nor is Mahler’s health, and as the trip progresses the two have memories and fantasies of what their lives have been—and of how they ended up in their current state. In other words, the film is an interweaving of memory and dreams and projections that’s given a form by a framing story. But this isn’t your normal framing story—and these certainly aren’t your usual flashbacks.

There’s a good deal more to the framing story than just a structure. Not only are the scenes on the train absolute marvels in technical terms (using wide-angle lenses and mostly natural light on an actual moving train afforded Russell some of his most beautiful images), but the content of the scenes is fully as important as the flashbacks. Nothing is without its point—even to the positions of the characters. While Mahler is constantly depicted looking away from the engine, Alma tends to be looking toward it. She has a future to look toward; he has not.

The fantasies in the film are definitely startling—and that’s announced from the very beginning where Alma is depicted as a creature trying to emerge from a chrysalis on a stony beach, making her way toward a stone head of Mahler and kissing it. Later fantasies are sometimes very short interpolations that serve to delineate the characters—as when Alma is presented as being little more than Mahler’s shadow. Others—especially a lengthy sequence in which Mahler envisions his own funeral and the more controversial sequence where his conversion from Judaism to Catholicism is presented as a silent movie—are complex, elaborate affairs.

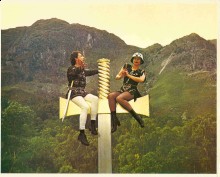

Not all of the fantasies are clearly defined as such. There’s a splendid scene early in the film that isn’t quite fantasy in the normal sense of the word, but which is certainly a stylized depiction of the event, where Alma runs about the countryside trying to quiet the sounds that are disturbing Mahler’s composing. It’s also a sequence that works on more than one level in that it’s a breathless depiction of the act of creation, but it’s also one of the film’s many instances that illustrate the subjugation of Alma as a person in her own right to the service of Mahler and his art, making the scene more than a simple celebration of creativity. It also recognizes the price that is often paid—not always by the creator himself—for that creativity.

One of the most moving and striking sequences in the film—where a heartbroken Alma has a “funeral” for a song she’s written—isn’t really a fantasy at all. Rather it’s a fantasticated memory—and interestingly, it’s not set to Mahler’s music, but to Richard Wagner’s “Liebestod” from Tristan and Isolde. Why not a Mahler composition? God knows, it’s not like there’s any shortage of funeral marches in the man’s symphonies. My take is that Alma’s not being let off the hook here for letting Mahler squelch her own dreams, and Russell’s conveying that by using a piece of music that is hardly shy of self-dramatizing.

The film is such a complex tapestry of memory, dream and framing stories that most viewers don’t even notice that Russell slips a memory of Mahler’s into one of Alma’s memories—and it really doesn’t matter anyway, because the film is so amazingly of a piece. This is filmmaking—and filmmaking of a kind we’ve rarely seen. When the film was first released critic David Sterritt, writing in the Christian Science Monitor, remarked that Mahler was a film “that throbs with life.” That struck me then—and strikes me now—as a perfect summation of this altogether wonderful work.

What ever became of Ken Russell’s Beethoven film?

I personally prefer The Music Lovers, then Lisztomania, then Mahler. The DVD I own, now out of print, is in a full frame presentation. I have no idea if it was filmed this way, or if it’s a pan & scan job. But everything looks in frame, so I’m inclined to think it was filmed in Academy Ratio. I find Mahler’s non-fantasy sequences a bit on the vanilla side. Which is frustrating, because the musical fantasies are some of the best things he’s ever done. I prefer The Music Lovers over the top acting.

Ken Russell always seems to me to be a silent film director who was born 50 years too late. The Devils is probably what The Passion of Joan of Arc would have looked and sounded like with modern technology. Vice versa, if you put The Devils in sepia, turned down the sound, and used intertitles, the over-the-top acting and accompanying music would be sufficient. Actually, it might almost play better as a silent film. I think Mahler shows his gift for matching music and image beautifully while still telling the story, no dialogue needed.

What ever became of Ken Russell’s Beethoven film?

The financing collapsed if I recall correctly.

The DVD I own, now out of print, is in a full frame presentation. I have no idea if it was filmed this way, or if it’s a pan & scan job. But everything looks in frame, so I’m inclined to think it was filmed in Academy Ratio

Well, in essence, everything that isn’t filmed in ‘scope is filmed in the Academy ratio (the very rare exceptions being hard-matted) and the image cropped by the mask in the projector plate. As a result, chances are that your side to side information is right, but the top and bottom includes image you were’t intended to see. This assumes Russell and Dick Bush were using a masked off viewfinder. Certainly they both knew that there weren’t a lot of 1.37:1 movie screens out there even in 1974.

I find Mahler’s non-fantasy sequences a bit on the vanilla side

I can’t say I agree with that, but that’s probably obvious.

Ken Russell always seems to me to be a silent film director who was born 50 years too late. The Devils is probably what The Passion of Joan of Arc would have looked and sounded like with modern technology

The first part of that seems to be an outgrowth of the notion that Russell doesn’t write good dialogue — a notion I don’t entirely agree with. But more, it’s such a sweeping statement that it seems to me that it fails to factor in so many things, starting with censorship and continuing to the idea that silent movies don’t become anything like as fluid as Russell’s films till the invasion of German directors like Murnau. Moreover, until sound you couldn’t have matched music and image with the precision Russell’s films require — nor could you effectively control silence. One of my favorite moments in Mahler is where the soundtrack goes absolutely dead on the word “death.” You couldn’t do that in a silent movie.

I would agree that Russell brings something of the silent movie aesthetic (at least the mature one) to film, but his films are almost equally reliant on their soundtracks.