Perhaps because it comes so close to the third film in his Antone Doinel series, Stolen Kisses (1968), François Truffaut’s Bed & Board (1970) doesn’t work as well as the other films in the five film series. It’s not a bad film, but it lacks the freshness of the other films. The joyful, sheer love of cinema playfulness that had marked The 400 Blows (1959) when Truffaut unleashed the French New Wave here becomes precariously mechanical. Truffaut was never going to duplicate the impact of that first film — a work that, along with, Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless (1960), freed film from the stiff and sterile 1950s, reintroducing personal film to a cinema that had largely become a corporate creation. (Granted, it would be a few years before English language movies caught up and made it their own.) Wisely, he never really tried, but he had managed to keep the subsequent Antoine Doinel films with something of that original buoyancy. Here, he falters — not disastrously, but noticeably.

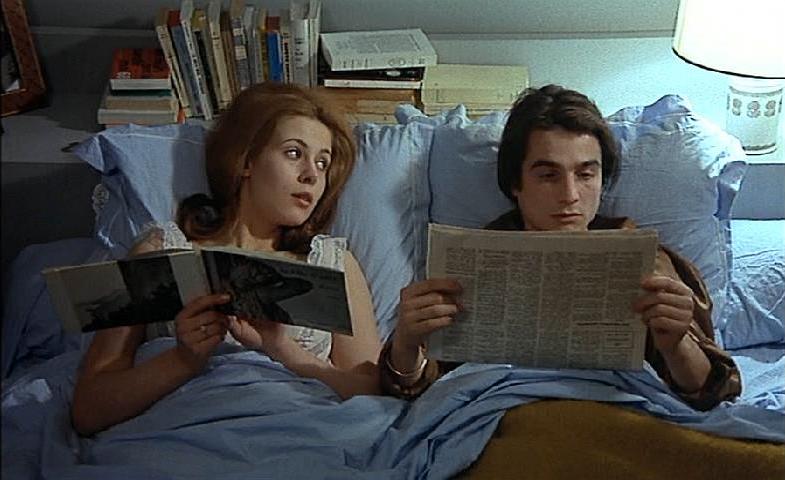

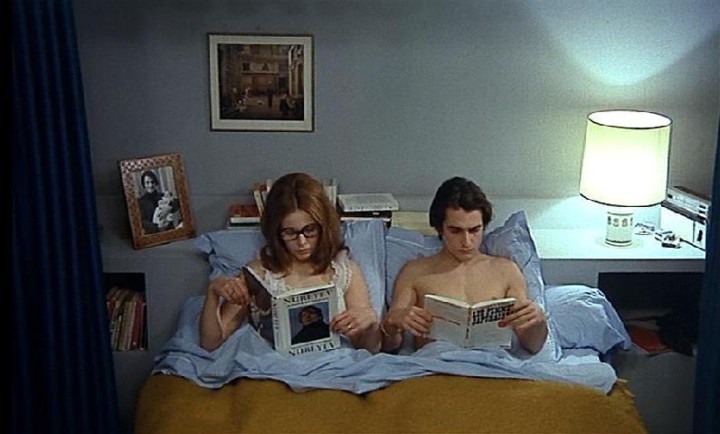

Part of the problem stems from the fact that the originally autobiographical quality of The 400 Blows had — by Truffaut’s own admission — taken on more and more of the personality of his star Jean-Pierre Léaud as Antoine as the films progressed. And while he’s engaging Léaud seems more self-centered and unsympathetic than Truffaut. Of course, that’s partly because behavior that is charmingly confused in a 14-year-old is a lot less lovely in a 25-year-old. Léaud at 25 is sometimes amusing, but also a little tiresome and not terribly likable on too many occasions. By the time of Bed & Board Antoine has married the girl from Stolen Kisses, Christine (Claude Jade), but seems no more settled than he was in any previous film. He’s too in love with doing nothing but that which pleases him. Marriage has not given him any particular focus or sense of reality. He has a “job” dying carnations for a local florist. He does things like buying a library ladder — even though he has no library. When fatherhood appears to sober him up a little and he has a completely undefined job — obtained by an accident of his employer’s self-importance — it mostly leads to an affair with a Japanese girl (Mademoiselle Hiroko) that undermines his marriage. By this point, the movie is keeping our good will strictly on the somewhat slender charms of its star and Truffaut’s undeniable panache.

Bed & Board does manage to right itself — more in comedic than realistic terms — by its end, but it never completely satisfies. Satisfaction is something we don’t get till the final film in the series, Love on the Run, in 1979. When put up alongside the final film, Bed & Board becomes a more pleasing proposition. But by itself it’s the weakest link on the series. I should note that the entire series is worth a look right now, since there are undeniable connections between Truffaut’s Antoine Doinel films and Richard Linklater’s current art house hit, Boyhood. Granted, Truffaut didn’t start out to create a series of interconnected films, and Linklater’s film did and is self-contained. Still comparisons are inevtitable — and Linklater would be the last person to deny the connection.

Classic World Cinema by Courtyard Gallery will present Bed & Board Friday, Aug. 22, at 8 p.m. at Phil Mechanic Studios, 109 Roberts St., River Arts District (upstairs in the Railroad Library). Info: 273-3332, www.ashevillecourtyard.com

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.