- Across from Plant on Merrimon Avenue, the Harris Teeter nears completion. Along with the grocery store, a fast-food drive-thru and a car-care center are coming. Straddling a main thoroughfare and a residential neighborhood, the development has a complicated history. Max Cooper

- At Chick-fil-A on South Tunnel Road. Max Cooper

- The house at 17 Eloise St. will be demolished to make way for another commercial building. In the meantime, it sits empty with a collapsing roof, broken windows, an overgrown yard and an unsecured entrance. The city’s development services department has no record of housing code violations. Max Cooper

- The intersection of Chestnut Street and Merrimon Avenue. Max Cooper

- Many Oaks NC Collection, Pack Memorial Public Library, Asheville, NC

When future diners at Plant sit on the restaurant's patio, they will look out on a Chick-fil-A drive-thru. It's a curious view for a nationally acclaimed vegan restaurant.

When Xpress confirmed Chick-fil- A's location in July, readers responded with more than 50 Facebook comments in just a few hours. Some looked forward to a chicken sandwich; others wrote long lamentations. But several simply wondered why a fast-food drive-thru would come to that location, which is about half a mile from downtown and adjacent to the residential Five Points neighborhood.

“I just don't see why in the world that would happen,” says Alan Berger, one of the owners of Plant. “We're touting ourselves as this food capital, and that's been drawing an awful lot of people here. It would seem to me you'd want to be developing a lot more locally grown businesses.”

Berger's not worried about the smell of fried chicken wafting onto his restaurant's patio (he's minimally concerned that Chick-fil-A's height might block the view of the mountains).

He says he knew a development was underway when he and his partners opened Plant two years ago — at that time, Harris Teeter had just announced it would be the anchor tenant.

But he didn't expect a drive-thru restaurant, or the traffic it could bring. That's understandable, since city law prohibits new construction of drive-thrus on most of Merrimon Avenue. (Existing drive-thrus based on old laws are allowed through grandfather clauses.)

“I think the assumption was, although this was a very 'hot property,' there would probably be some small shops that would go in there,” he says. “There needs to be a dialogue about where the city's going and what's needed and how you achieve that balance between business and growth and residents.”

Turns out, that dialogue was happening about the time Berger moved here eight years ago.

According to the U.S. Census, Asheville’s population grew 21 percent between 2000 and 2010, so for many recent-comers, history is news. Since 2005, the property at the corner of Merrimon Avenue and Chestnut Street has entangled neighborhood residents, business owners and City Council members in a debate about what Asheville should look like in the future.

As the Harris Teeter development takes shape — and as neighborhoods in West Asheville plan ahead — a look at the past reveals the struggles neighborhoods encounter as they grow.

Get to know the nest

Merrimon Avenue — or U.S. Route 25, as it's known to the Department of Transportation — cuts due north out of downtown. It links with Broadway Street near the Interstate-240 overpass, Broadway's nightclub and Rosetta's Kitchen. From there, it passes through acommercial district of restaurants, grocery stores, schools, churches and gas stations. The buildings sprang up at different times throughout Asheville's history, and each one reflects the city laws of its day.

At Beaver Lake, Merrimon swings west and becomes mostly residential until it leaves the city limits.

Many neighborhoods sit a block off Merrimon. Five Points is the closest one to downtown. It's an area of narrow streets, crooked intersections, vintage bungalows and brick apartment buildings.

Chris Peterson has lived near this part of town all of his life. "I know every square inch of north Asheville," he says. "I know every alleyway and the neighborhoods and everything.”

He owns some of it, too, including a share of the Atlanta Bread Company building at 633 Merrimon Ave. (He also owns Magnolia's restaurant and Cinjade's nightclub downtown, and he served as Vice Mayor in the early '90s.)

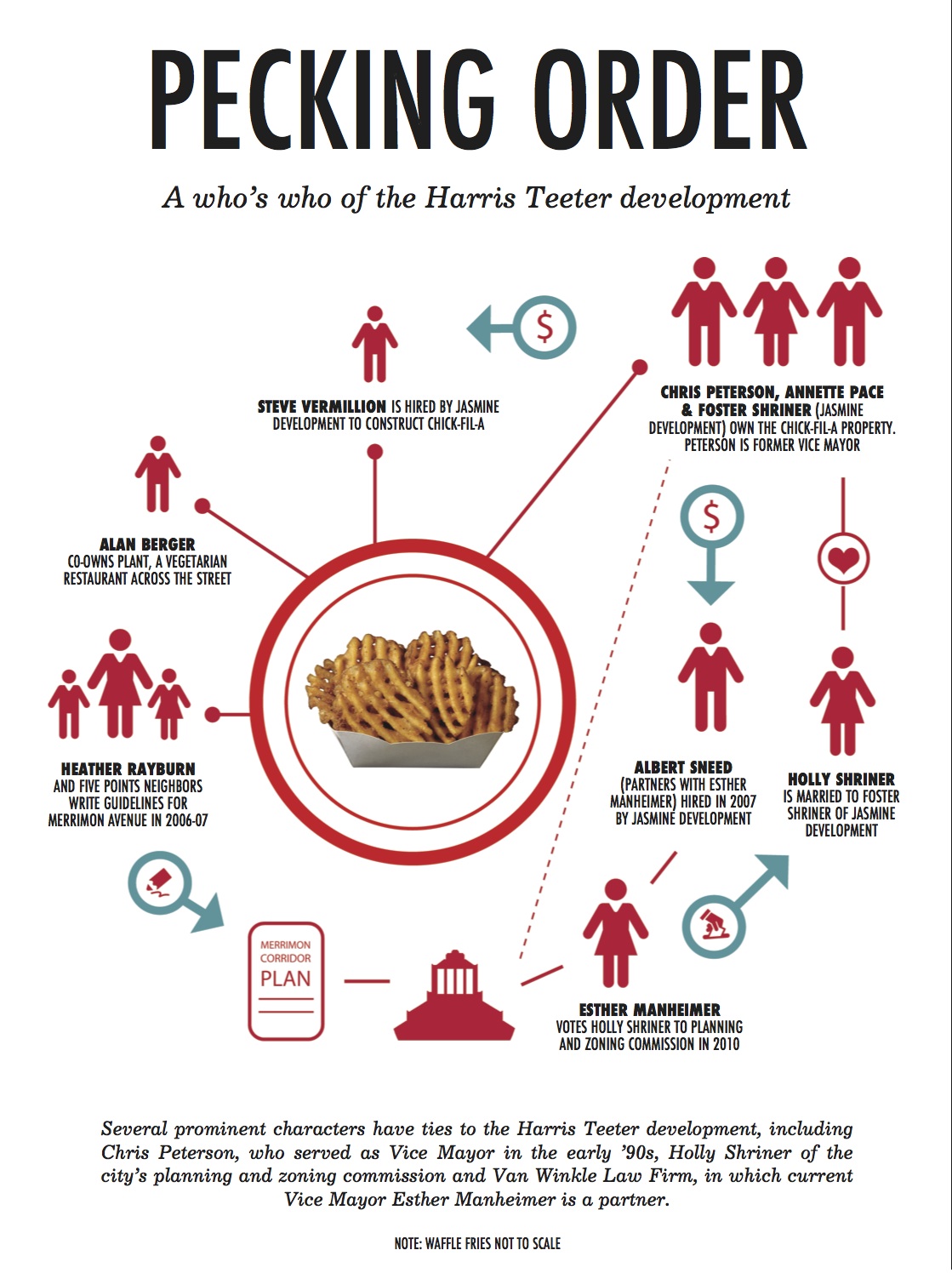

In 2005, Peterson bought the property where Harris Teeter now sits, along with partners Foster Shriner, an accountant with offices on Merrimon, and Annette Pace of Asheville Waste Paper. (Together, they make up Jasmine Development).

When investors like Peterson and his partners buy a piece of property, they make plans to build on it according to the city's zoning ordinances. These laws deal mostly with use. That is, they talk about the type of business that can open on a plot of land.

Most of the city's current zoning code dates to 1997. At that time, the Harris Teeter site was home to Deal Buick, an auto-sales lot, so it was zoned like a car dealership. When the business closed, the zoning — Highway Business — remained.

It's the only Highway Business property nearby — most of the others are on Tunnel Road or Smokey Park Highway.(There’s a pocket on the north end of Merrimon).

The rules for these properties are pretty wide open, allowing for a variety of businesses. New drive-thrus are a clear sign of Highway Business Zoning because they're prohibited in most other zones. Auto and boat repair shops are also indicators.

In short, Highway Business Districts are all about the car. "Automobile-oriented development” and the “dominance of the automobile” are norms, according to city code.

On Merrimon Avenue, most properties have more regulations than the Deal Buick site.

The property's designation as Highway Business, among its other assets, appealed to Peterson and his partners; they knew they had plenty of leeway, which they hoped would make developing easier. “If you're going to buy a commercial property, you better know what your zoning is,” he says. “You don't want to buy a piece of property and have to fight about it."

Hatching ideas

About the time Peterson and his partners purchased Deal Buick, a group of city staffers and homeowners began planning the future of Merrimon Avenue.

The city had already created the groundwork for their efforts by adopting the Asheville City Development Plan 2025 (better known as the 2025 Plan), which outlines goals and strategies for city growth.

City staff and a group of 60 volunteers worked on the 2025 Plan for two years. Several of them carried on their efforts by creating the Merrimon Avenue Corridor Study Group.

They took their directive from the 2025 Plan: “The City should revise … standards for primary corridors to ensure that the corridors are developed in an urban manner.” (As opposed to “its alternative — sprawl.”)

Their goals? Change the zoning on all of Merrimon Avenue, including the Deal Buick site, to promote greater density and new, pedestrian- friendly development.

Heather Rayburn, who has lived on Mount Clare Avenue since 1994, worked on the study. Today, she’s instrumental in the Five Points Neighborhood Association.

“We had public meetings: Everybody was invited to give feed- back,” she says. “We did this in good faith.”

The city publicized the effort as early as 2006. Still, many Merrimon property owners say they were caught unaware.

Peterson’s partners, Foster and Holly Shriner, were among them. Along with Deal Buick, Foster owns several other properties on Merrimon. One of them houses his accounting business.

“I think the property owners felt the rug had been jerked out from under them in the sense that we didn’t know anything about it — or we didn’t know enough about it,” Holly says. “So it was this scramble to figure out what they were even talking about.”

In response, some business owners sought legal assistance. Peterson and his partners hired Albert Sneed of Van Winkle Law Firm to keep the Deal Buick site zoned the way it was.

“We were just protecting our property rights,” Peterson says. “We’re really not in the neighborhood. We’re facing Merrimon Avenue, which is a state highway.”

But neighborhood residents were also concerned. “The zoning is in place to protect everyone’s property values,” Rayburn says. “It’s in place to further the city’s goals.”

The business owners’ ire spooked the city. At an Aug. 14, 2007 meeting, Mayor Terry Bellamy said she couldn’t sup- port the movement to rezone Merrimon. She acknowledged the community’s 22 months of work, but suggested the project was “creating a monster,” according to minutes.

Council asked the community to continue working and return with a proposal that satisfied business owners and residents.

But the groups never followed up with the city. After two years of effort, Rayburn says, many residents felt too discouraged to carry on.

Peterson says negotiations were difficult all along.

“Neighborhood people already have their set view on people who are in business, and business people have their damn views,” he says. “It’s like cats and dogs.”

Almost a golden egg

As the Merrimon Avenue Corridor Study was sputtering, the partners started planning an “urban village,” which would include condos, a hotel, retail, a small amount of affordable housing and underground parking. The proposal required City Council approval.

“The original plans were phenomenally beautiful, and it would have been the first true urban village in Asheville,” Holly says. “We wanted an urban village. We didn't get the urban village.”

If the plans had been successful, the permissive regulations that go with Highway Business zoning would have been changed (and no drive-thrus would’ve been possible).

What happened? First, the community protested. The condo towers would have been 10 stories high, and residents worried about the towers' shadows. They submitted a protest petition that stalled the development for a few months.

In January of 2008, the condo project, Horizon's, was to go before City Council for review, but the owners asked for more time to work with the neighbors, according to minutes from that meeting.

But larger forces stalled the negotiations: The housing crisis of 2008 ensued, and most everything stopped.

Incubation

The property lay dormant for about two years. Developers were going bankrupt. Proposed projects in other parts of the city halted.

The urban village stayed on Council’s books until November 2010, when it was withdrawn.

But all the while, Holly had been thinking about city planning. She had been a volunteer in the schools, but her kids were getting older, and she was looking for a different outlet, she says.

Earlier that year, in February of 2010, she applied for the Planning and Zoning Commission, a group of citizens that makes recommendations to City Council on development projects. They're appointed by Council, and they review building plans to determine whether they're legal and in line with the city's goals. They work with the zoning code, as well as the 2025 Plan.

“I was shocked I got appointed,” Holly says. “The other people that applied had higher credentials than I had. I thought, 'They're going to pick this planner or they're going to pick this architect or whatever,' because they had much stronger resumes.'”

Other candidates included Mark Brooks, an engineer (who was also elected to the commission) and two who were denied: Joe Minicozzi, an urban planning consultant (and fourth time applicant) and Russ Towers, a real estate broker.

Holly submitted her application on paper from her husband's accounting office, but Council members didn't notice her connection to the Merrimon Avenue property. At that time, candidates weren't required to reveal what properties they owned. (The application process changed a couple of months later, after officials recognized the inherent problems with that situation.)

Holly wasn't the only one surprised by her appointment. “We were shocked that they put Holly Shriner on that board. It's a huge conflict of interest,” Rayburn says. “We keep wanting the city to help our neighborhood, and we want our City Council to be a champion for everybody, everybody in the community. And they put one of the investors on the P & Z?”

Vice Mayor Esther Manheimer voted for Holly's appointment in 2010 (a 4-3 vote, with Terry Bellamy, Jan Davis, Manheimer and Bill Russell voting for her and Cecil Bothwell, Brownie Newman Gordon Smith against), and again for her reappointment in 2012 (another 4-3, with Davis, Marc Hunt, Manheimer and Smith in favor and Bellamy, Bothwell and Chris Pelly against).

Manheimer stands by her decision. “You've got to pick people that are reflective of the community, that represent a cross section,” she says. “And all of us are not architects, engineers and planners.”

Under the city’s rules, Shriner must recuse herself from votes on her husband's property. “I understand that this is a big project, and I understand that there's some controversy over it,” she says. “I purposefully stay out of it.”

Game of chicken

In December of 2010, Harris Teeter confirmed its Merrimon location.

In addition to Harris Teeter, the property owners wanted to build three other buildings. They needed more land.

Between them, the partners own several houses on Merrimon Avenue and Eloise Street that they wanted to lump into the development, but they needed Council approval to rezone them.

In late 2012 and early 2013, the developers brought the rezoning request to the city, along with plans for the additional buildings. The neighborhood and the city saw the rezoning process as a chance to negotiate.

“Conditional zoning is an opportunity to load on some extras,” Manheimer says. “We get a bigger buffer. We get a better setback. We get more vegetation planted. We get better pedestrian access, more sidewalks.”

The neighborhood made requests, too. “We agreed we wouldn't oppose the rezoning of those lots up there if they met certain conditions,” Rayburn says. “We really didn't want any drive-thru.”

Neighborhood residents brought their concerns to Council. They worried about cut-through traffic on their neighborhoods' narrow streets, fumes from idling cars, odors from fast-food dumpsters and late-night activity on the property.

But Council felt it couldn't eliminate drive-thrus altogether, since the developers had a right to the Highway Business zoning — and the drive-thrus — on the majority of the property.

Even if Council didn't allow the property owners to add extra land to the development, drive-thrus were still legal on Deal Buick.

Council tried to determine how to get the most out of the bargain, Manheimer says.

“There's kind of a game of chicken there,” she explains (without irony). "If they're going to do one [drive- thru] no matter what, can I do a con- ditional zoning where they get their one, but then we get a whole bunch of other stuff?”

Council negotiated the rezoning in February, after two meetings. They allowed for one drive-thru.

In return, Council negotiated the location and hours of the drive-thru, about $30,000 to use toward pedestrian improvements near the property, signage to restrict truck traffic in the neighborhood and an anti-idling policy for delivery vehicles.

Manheimer says she doesn't think the development is at its best, but it's reality. "I'm not in favor of any kind of development that replicates urban sprawl, especially in our urban corridor," she says. "Everybody doesn't get everything they want."

Holly wasn't allowed to vote on the property since her husband owns it. But if she could have, she would have approved it, she says.

“I am very proud of what my husband's doing … of what he and his partners are trying to bring to Asheville,” she says. “They had a vision. That's what people do. We're in business to have a life and provide for our family.”

Bird in the pot?

Responsibility for the project now rests with the owners and the development firm they hired to manage the construction, Merrifield Patrick Vermillion. From here on out, the city simply enforces laws that are already in place.

Chick-fil-A’s building will be complete by early 2014, according to MPV. Behind it, the developers are building a AAA Car Care Center that will offer oil changes and repairs.

The houses at the corner of Merrimon and Eloise will be demolished to make way for a third building.

Peterson says the development represents progress, no matter what stance one takes on Chick-fil-A.

“Deal Buick was an eyesore before we tore those buildings down, and now it’s going to have jobs and a tax base,” Peterson says. “It’s going to have a lot of vegetation and stuff that we bent over backwards for. I think everybody will be happy, and I hope they are.”

While Rayburn has qualms about the drive-thru, she says she’ll probably shop at Harris Teeter. “At least that’s a use where we can walk to get our groceries,” she says.

After almost a decade of vacancy, the property has tenants. Harris Teeter opens in September.

But in the city’s zoning code, the Highway Business District remains. Manheimer hopes that the law can still change.

Planning progress in other neighborhoods could set a positive example for Merrimon.

In West Asheville, citizens and property owners are collaborating on a zoning project, the Haywood Road Vision Plan. The city has hired a consultant to help them, and a series of community meetings start this month (see box for more details). If they’re successful, Manheimer says the momentum from Haywood Road could bring change to Merrimon Avenue.

“I have pretty strong feelings about this, and I think that they’re fairly progressive,” she says. “My personal goal is to push [Haywood Road’s rezoning] through, and then let’s go back to Merrimon, take two, and do it.”

Very thorough reporting on this article, but I also appreciate the subhead puns and especially the tongue in beak nature of the (waffle-fries-not-to-scale) chart graphic!

A couple of comments about Peterson:

1. His first line of defense on every issue that could impact him is “we weren’t told about it”. Always a lie, always a stall.

2. He bought the mayor a long time ago. Any time her vote or position looks odd, compared to her philosophy,you’ll see peterson’s mug in the background.

Congratulations N. Asheville NIMBY’s! Since you didn’t go with door #1, the better designed urban village, let’s take a look at what’s behind door #2. It’s a backwards looking chain supermarket, a drive-thru chicken fryer, and a chance to be oiled and lubed! Thanks for playing, Let’s Make a Stink! Buh Bye now.

These people need to get over themselves. They are ONE BLOCK from Bojangles and Asheville can’t just cater to pretentious rich people… the poor people who staff those fancy restaurants have to eat somewhere.

Sorry to say this but putting all of those things in that area is like squeezing a 12 Lb. clusterf*** through a straw. Has the city thought about traffic flow? Based on previous city design work, I’m guessing not. Merrimon Ave. has need turn lights at EVERY intersection for the last 10 years or more. Much less turn lanes for those nonexistent green arrows. How about we work on better housing, better roads, better (non service industry) jobs, and better way of life in general. Instead of how we can attract more tourists and how good our food, beer, and crafts are going to sell to them.

LOL. As if adding a Chick-Fil-A is a tourist attraction.

I drove ten hours to eat at plant and see the vegan options in the area and consider it as s vacation /retirement option or actual as a home.

I am very disappointed to hear a city council is possibly succumb to graft by giving tax free status to such organizations as Chick fil A, in such s location as to destroy the very thing that attracted me.

Forks over knives a film plant and others might want to show in town to get the point across this the future this is working class…