Many films dealing with hot-button topics like AIDS digress into sensationalism without adequately developing character or story, relying on the merely salacious to sell tickets when a more nuanced touch would be far more effective. Fortunately, writer/director Robin Campillo’s Cannes Grand Jury award winner BPM (Beats Per Minute) deftly sidesteps that particular pitfall, delivering a thoughtfully composed love story set at the height of the AIDS epidemic.

This unlikely romance blossoms between Nathan (Arnaud Valois) and Sean (Nahuel Pérez Biscayart), a pair of activists working with ACT UP Paris, a group of radical demonstrators who advocate for AIDS awareness through acts of civil disobedience. What makes the incipient love story that develops between the two young men so problematic is that Sean is HIV-positive, while Nathan is not. The script, from Campillo and Philippe Mangeot, doesn’t cop out on the inevitably tragic conclusion of this coupling, but the path it takes to get there is both brutal and believable.

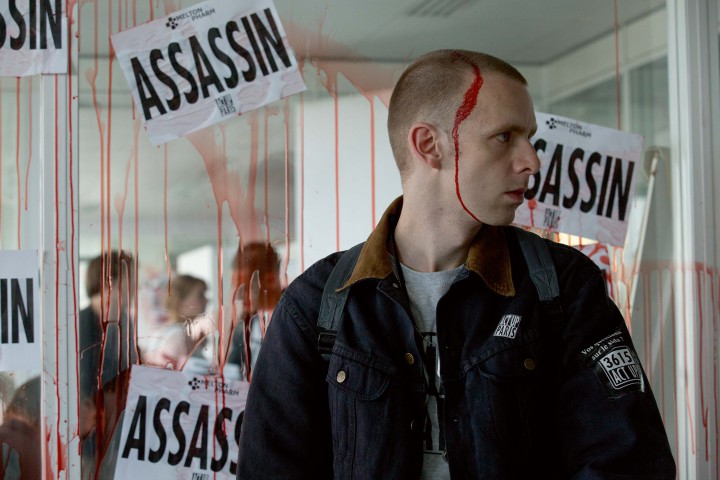

Campillo has an eye for chaos — from the anarchic tumult of insurgent actions like breaking into a pharmaceutical research office and pelting the walls with fake blood to the simmering tension of planning sessions in the group’s lecture hall headquarters, his camera finds the conflict at the core of each scene without calling attention to itself. His aesthetic veers from cinema vérité to expressionism as he captures dance parties fueled by house music and desperation, his characters frantically clinging to life with the specter of death never far from the margins.

While ACT UP’s actions would likely be classified as domestic terrorism in this day and age, BPM tells the story of an arguably simpler time when AIDS and not al-Qaeda was the boogeyman du jour and civil dissent was a more open endeavor. But Campillo forgoes the nostalgic allure of his period setting, favoring a timeless quality that brings a sense of timely immediacy to his subject. Yes, it’s a film set in the Nineties, but many of the problems addressed by ACT UP remain largely unresolved — and yet Campillo avoids sermonized moralizing, focusing instead on the human cost of ignorance and bureaucratic foot-dragging.

If there’s a complaint to be made against BPM, it’s that its aesthetic shifts are not always gracefully navigated — at times it plays as though the film is vacillating between early Danny Boyle and late Jean Rouch, often within the space of a few frames. But the heart of the film, expertly handled by Valois and Biscayart, remains indelibly resonant. While BPM may draw cursory comparisons to last year’s Moonlight, it’s an altogether different beast — one with something substantial on its mind. If Moonlight was a film about finding identity in conflict with culture, BPM is a story about clinging to humanity in the face of gruesome and unavoidable death and loss. As far as themes go, they don’t get much more universal. Not rated.

Now Playing at Grail Moviehouse.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.