Politics not withstanding, I doubt anybody could deny that Ruth Bader Ginsburg is a remarkably impressive person. From her career as a lawyer crusading for gender equality to her decades as a Supreme Court centrist, Ginsburg has cut a swath of rationality through a landscape littered with ignorance, bigotry and institutionalized sexism. That Ginsburg, midway through her 80s, has become something of an empowering icon for modern youth is the heartening core of documentarians Julie Cohen and Betsy West’s lavish love letter of a film, RBG.

Unfortunately, it’s Ginsburg’s meme-generating late-period public image renaissance that also hamstrings Cohen and West’s documentary approach. The duo devote as much time to jokes about her apparently lacking skills in the kitchen or the collection of lace collars she wears under her judicial robes as they do to her laudable record as a jurist arguing cases before the Supreme Court — she won five out of six cases — or her indefatigable work ethic, sleeping four hours a night to finish law school and raise her children in an era when women were encouraged to aspire to homemaking and little else. If Cohen and West’s venerative tone is duly justified by their subject, it also seems to do something of a disservice to it, at times glossing over human complexity in favor of social-media-ready sound bites.

Still, the fixating presence of Justice Ginsburg is the draw here, and in that regard, RBG does not disappoint. The film is at its best when Ginsburg speaks for herself, her self-evident integrity and clarity of mind shining like a beacon from a time in which political discourse consisted of more than vitriolic name calling and rage-fueled tweets. Some of RBG’s most compelling moments come when it turns its focus to Ginsburg’s ideological opponents like Orrin Hatch or examines her longtime friendship with the late Antonin Scalia, but these moments are few and far between.

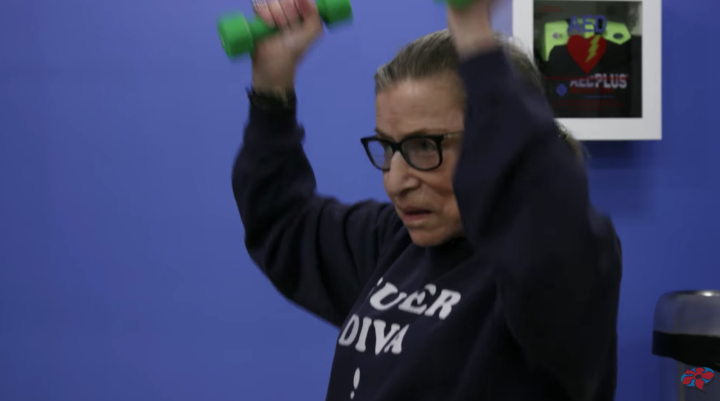

RBG makes great strides in humanizing Ginsburg, particularly in its examination of her college sweetheart and husband, Marty, a convivial yin to Ginsburg’s introspective yang. The film posits Marty’s unwavering support of his wife’s career path as one of the central factors in Ginsburg’s rise to the nation’s highest court, and here again Cohen and West seem to lose the thread — rather than couching his early fight with cancer while Ginsburg was a new mother still in law school as a definitive event in her early development, it’s skirted briefly in favor of getting back to more shots of the justice working out in her “Super Diva” sweatshirt.

Despite its occasional superficiality and distinctly youth-oriented bent, RBG remains valuable for its focus if not its insight. Ginsburg’s dissenting opinions on the bench may have rendered her as an unlikely firebrand, but her integrity is beyond reproach, and there can be no question of the validity of her impact on the political and social discourse on the country. While Cohen and West’s treatment of their subject may be frustratingly lacking in depth for some viewers, it’s glowing portrait of an undeniably charming and engaging personality bears the potential to introduce Justice Ginsburg to a new audience, and in so doing, awaken them to the possibilities of enacting social progress without rancor. That, in and of itself, is a good thing. Rated PG for some thematic elements and language.

Now Playing at Fine Arts Theatre.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.