Two years ago, Amanda Layton applied for a job at a restaurant and found an unexpected opportunity for a fresh start.

It was a management position at MOD Pizza in Asheville. The interviewer revealed that the nationwide chain is a second-chance employer, meaning it hires people reentering the workforce after incarceration. In many cases, people who were incarcerated are also in recovery from addiction.

Layton, who left prison in 2018 and was embarking on recovery again, says she “was almost in tears” at the interview. She recalls, “The guy was like, ‘What’s wrong?’ And I was like, ‘This is me! This was meant to be! This is me you’re talking about!’”

MOD hired Layton in 2021, and her district manager “understood, and he wasn’t judgmental at all” that she was in recovery. Other restaurant jobs had felt like a dead end. But she says the trust and responsibility that came with a management role boosted her confidence and gave her an opportunity to shine.

During Layton’s 1 1/2 years at MOD, she hired other people who were in recovery or reentering the workforce after incarceration. “I’ve found that people who need that second chance were my best employees,” she tells Xpress.

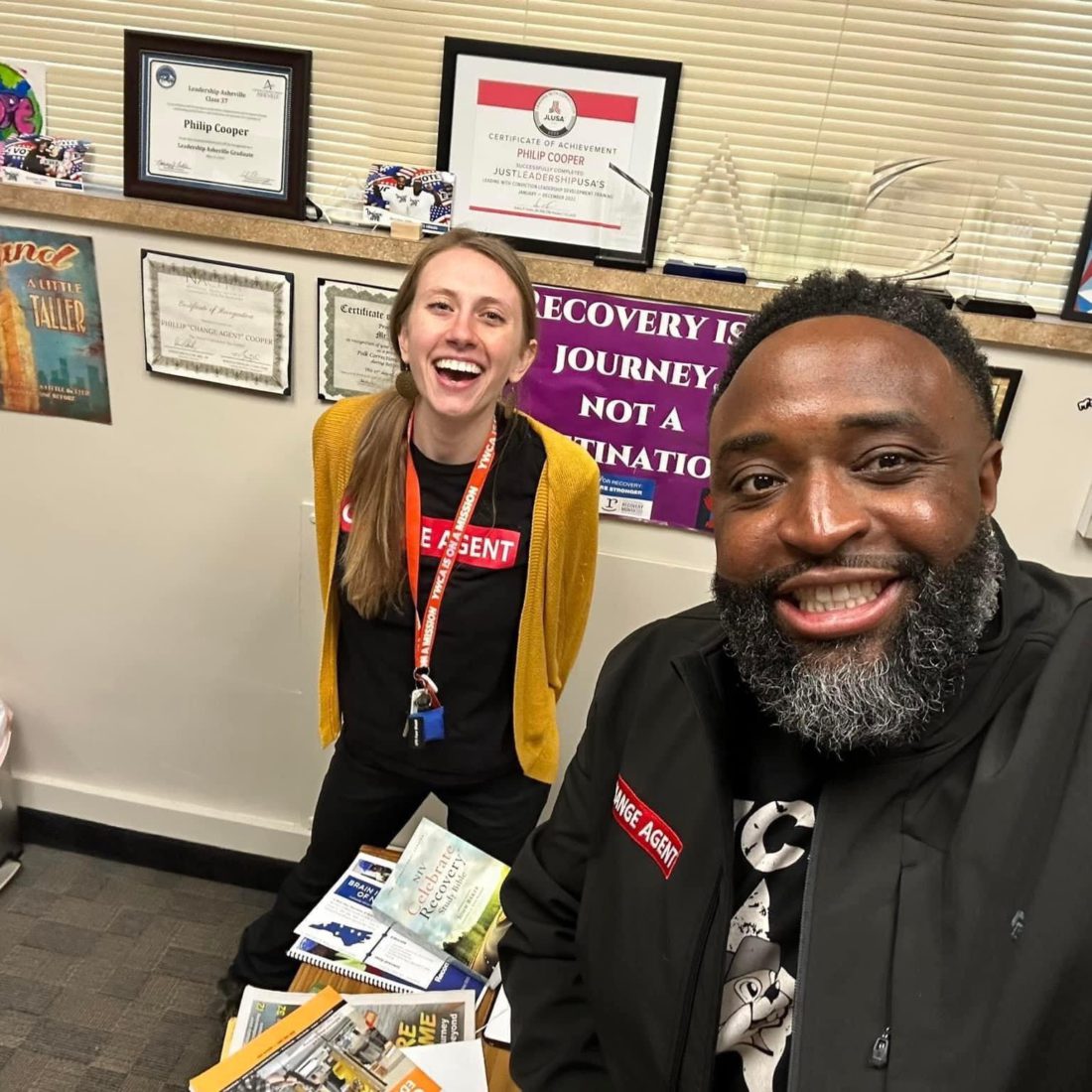

Today, Layton, who celebrated three years in recovery on Jan. 10, helps others get their lives back on track. In addition to being a certified peer support specialist, she’s an advocacy coordinator for an initiative with Operation Gateway that connects people in recovery with recovery-friendly workplaces.

Workplaces that hire and then support people in recovery are helping these individuals get their lives back on track, says Operation Gateway Executive Director and founder Philip Cooper. “Being a recovery-friendly employer is a big game changer,” he says.

Meanwhile, advocates are identifying workplaces in the community that are already recovery-friendly and encouraging more employers to become so, explains Sue Polston, executive director of Sunrise Community for Recovery and Wellness and a peer support specialist. They’re also offering a helping hand to employers who need more information on how to best support these workers and their needs.

The importance of second chances

Federal law permits employers to take a person’s criminal record into account with final decisions on hiring, according to the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. People with certain criminal records are prohibited from some jobs. But other than those circumstances, the EEOC encourages employers to consider whether the individual’s criminal history is actually relevant to the “risks and responsibilities of the job.”

Yet some people in recovery or who reenter the workforce after incarceration find that potential employers won’t even interview them. This happens most with felony charges, especially drug-related ones, and the stigma that those charges carry, explains Tess Monty, a certified community health worker, certified peer support specialist and “change agent” with Operation Gateway.

Some employers do, of course, hire individuals regardless of their pasts. But that pool of employers can be small and may not always meet the worker’s needs, like supporting a family. In 2021, a formerly incarcerated person one year after exiting prison earned a median annual wage of $7,343, according to the N.C. Department of Commerce Labor and Economic Analysis. (The federal poverty guideline is $15,060 for one person in 2024, per the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.)

Polston struggled with that situation herself. “I can speak from my own personal experience 10 years ago plus,” she says. “On paper, I am a thief. My charges are all larceny charges. Who’s going to trust me?” After prison, her only job offer was at a fast-food restaurant that paid $7.25 an hour. The wage was so low that she struggled to afford her transitional housing and basic necessities like toiletries. She says having such few job opportunities available to her was “very frustrating.”

Lack of support for recovery can create stumbling blocks and stress for folks who are otherwise on a positive track, explains Monty. For example, a worker in recovery may not be able to pick up a last-minute shift or have flexible schedules on certain days because of recovery meetings or meetings with parole officers. But advocates encourage employers to reframe a worker’s commitment to those responsibilities as a testament to their resilience and determination. They also suggest that workers in recovery may have more gratitude for being employed, as well as a stronger work ethic due to a desire to prove themselves.

Those attributes can apply to individuals reentering the workforce after incarceration as well. “People coming out of prison are very motivated and passionate about finding a job and getting their lives together,” says Monty.

Supporting recovery together

Supporters of recovery-friendly workplaces are reaching out to businesses one by one. PRISM founder Marilyn Shannon, who is based in Wake County, says her nonprofit has collated databases of businesses in numerous local industries, including manufacturing, hospitality and construction. It also has databases of the largest employers in Asheville, Hendersonville and the region. She cold calls businesses on the list, asks to speak to the person who does the hiring and then explains the benefits of being a recovery-friendly workplace.

According to the N.C. Department of Commerce Labor and Economic Analysis, North Carolina had only 0.9 job seekers per job opening in April 2023, and only one job seeker per opening in October 2022. “Most businesses need employees, so when I can get to educate them about this pool of people, who are wonderful, loving, great humans, they’re interested,” Shannon says. (PRISM hosted a conference Jan. 17-18 in Hendersonville for employers and human resources managers on recovery-related topics in the workplace.)

When businesses decide they want to be recovery-friendly, Shannon connects them with Kit Roberts, director of recovery-friendly workplace programs at WCI, an employer association based in Asheville. In September, the N.C. Workforce Development Coalition, which is part of WCI, received a nearly $300,000 grant from the Appalachian Regional Commission. The award allows Roberts to directly engage employers about how substance use disorders impact their workforce, and the how and why of becoming recovery-friendly.

Businesses recruited to the cause get help connecting to potential employees. Operation Gateway has a list of recovery-friendly businesses and employers in Asheville, and the initiative assists with placing people in environments that will be supportive of their needs. These employers can also learn about trainings addressing recovery and mental health topics from peer support specialists. A discussion on how to informally certify local businesses — much like the statewide nonprofit Recovery Friendly NC designates businesses as recovery-friendly — is underway.

Normalizing the conversation

Employers need to be realistic about the fact that some employees use drugs, some may be in active addiction and some may be in recovery, says Cooper. Employers shouldn’t assume they’ll never have to address the situation of an employee who has overdosed or an employee who becomes active in their addiction again. Avoiding these topics keeps real issues in the workplace under wraps, he believes. Secrecy related to recovery, addiction and mental health can be harmful to employees — even deadly.

“Whether they want to be recovery-friendly or not, they’ve got people at their companies that do drugs, so it would behoove them to be knowledgeable about resources,” Cooper says.

He suggests posting signage in common areas as a way for employers to acknowledge their workers’ needs. He recommends posting information about 988, the federal suicide hotline, and information about recovery support. Even small gestures like that can destigmatize private struggles.

“Being recovery-friendly requires a company to normalize the conversation about recovery as well as addiction,” says Cooper. “It’s an environment where people don’t get caught off guard if you’re talking about drugs or overdoses.”

UPDATE, Tuesday, Jan. 30: This article has updated Sue Polston’s job title.

Great article about important efforts to support recovery and the incredible community of leaders in WNC. Just a clarification, Sue Polston works for Sunrise, not PRISM.