Target Corp. this spring shook up the typically staid bridal business by marketing a silk-and-polyester scoopneck Isaac Mizrahi wedding dress—for $159.99. In an industry that still looks askance at money dances and cash gifts—no matter how many times a Bridezilla stomps her foot and wishes it were otherwise—the retailer’s unabashed fusion of frugality and frills raised a few eyebrows:

“This isn’t an everyday purchase,” sputtered one independent bridal showroom owner to a Knight Ridder reporter last month.

“It’s not like picking up paper towels and a blender,” added Karen Rolfe of The Bride’s Room in Wheeling, W. Va. “Nobody likes to pay designer prices, but the fabrics are better and you look better in it.”

It’s an argument Rolfe and her colleagues are destined to lose. Since the mid-20th century, American design has been perpetually repositioned within reach of the working class. Designers have successfully exploited new technologies and materials to democratize fashion, so Americans now accept—and expect—pretty things at low prices.

The story of cheap chic’s ascension is the subject of two concurrent exhibits opening this week at the Asheville Art Museum: Living by Design: Mid-Century Modern and Groovy Garb: Paper Clothing From Mars Manufacturing Company.

“There are some interesting linkages between the two shows,” says museum curator Frank Thomson. “They’re both looking at the idea of design in life, and how you can make things easy and affordable.”

Living by Design features chairs, kitchen wares and other home items designed by such well-known names as Charles and Ray Eames, Russel Wright and Eva Zeisel, lent to the museum by area collectors. The sensible pieces all convey the sense of progress and cheer that became a linchpin of the new Modernist movement: “Between the end of World War II and the mid-1960s, it was a fairly optimistic time, if you ignored that pesky nuclear war,” Thomson says. “There was a belief that problems could be solved.”

By utilizing new and inexpensive materials, designers working in the mid-century-modern idiom were able to produce pieces that most ranch-house owners could afford. Americans no longer had to take out loans for a good, heirloom-quality dining set.

Up in smoke

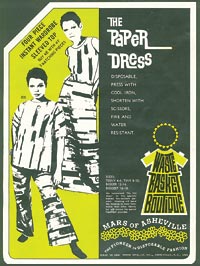

The paper clothing included in Groovy Garb was never meant to last. Although Mars’ frocks could be washed—carefully—their disposability was a large part of their appeal. In the optimism-challenged Vietnam War era, thinking about tomorrow had become passé. But if paper fashion couldn’t match the durability of mid-century-modern furniture, its emphasis on affordability and accessibility made it a natural extension of the earlier movement.

The paper dresses, jumpsuits, bikinis and swim trunks included in Groovy Garb were drawn from the personal collection of Bob and Audie Bayer, who in the late 1960s were selling 80,000 paper dresses a week from their Asheville manufacturing company.

“Paper clothing, apparently, is here to stay,” TIME magazine reported in 1967.

The Bayers never thought so: They were surprised the fad lasted as long as it did.

“They were horrible,” Audie says of the paper dresses she dutifully modeled, including a silver, floor-length gown she wore to a New Year’s Eve party at the Grove Park Inn. “The paper wasn’t real comfortable. It felt like … you know the napkins they say feel like linen, but don’t? They were scratchy, they were uncomfortable. I don’t know why people bought them, but they were all the fad.”

Erica Rasmussen, an associate professor of studio art at Metropolitan State University in St. Paul, Minn., insists paper isn’t as novel as everyone thinks. While she admits “paper garments sound like an oddity to contemporary ears,” she’s traced the history of disposable clothes back to 10th-century Japan, where monks would ritually shed their paper robes at the end of each season and burn them.

(As it happens, the propensity of disposable garments to go up in flames may have contributed to their disappearance from the American style scene: Folks in the 1960s liked to smoke, and ashing on a dress of gathered, spunbonded Oliphant—banish the thought of fashionistas sheathed in college-ruled writing paper—often had disastrous consequences.)

“Paper was in such abundance in the East,” says Rasmussen of paper clothing’s royal roots. “The nobility had very fine garments made.”

The disposable outfits which surfaced in the 1960s served a very different purpose, she points out.

“Buyers were primarily young women who were fashion-forward, and maybe even career-oriented,” says Rasmussen. “Everything was being marketed as saving time and energy.”

The first paper dress to hit the United States was a $1 sleeveless shift offered by Scott Paper Co. as a promotion: The 1966 dress was dismissed by old-guard fashion mavens as a “paper gag.” But even before sales had topped the half-million mark, Bob Bayer suspected the company was on to something.

Bayer, who had studied mechanical engineering at Cornell University, had earlier tried to sell the U.S. Army on disposable underpants, which he figured would be useful in Vietnam. The Army tested the product, but soon realized it wouldn’t do for the field: “They worked pretty well, but they didn’t have good abrasion resistance,” says Bayer. “I didn’t think that would be good.”

When Bayer learned of the Scott Company’s gimmick, he immediately began transforming his father-in-law’s ailing West Asheville hosiery mill into a paper-garment factory. He assigned design duties to his wife, whose only experience with fashion was a stint as an editorial assistant at the Ladies’ Home Journal.

“I don’t know how I did it,” Audie Bayer remembers. “I had total control and I didn’t know what I was doing. It was such fun.”

“My wife really made the thing tick,” says Bob.

Bayer would draw the dresses—“I sized them teeny-tiny, bigger and biggest,” she says—and then visit a gift-wrap printer to choose patterns off his rolls.

“The printer who printed gift wrap could print on paper,” explains Bayer. “I would sit and say, ‘I like this one and that one and that one.’”

The Bayers’ Mars Manufacturing Company beat Scott to retail, and soon had “waste basket boutiques” set up in all the fancy New York City department stores, including Macy’s, Gimbels and A&S.

“People at that time were experimenting with a lot of new things,” offers Bob Bayer.

One of the company’s most popular designs was a “paint-your-own” dress, two of which were purchased and painted by Andy Warhol.

“Those ended up in the Brooklyn Museum, not in our house,” reveals Audie.

The Bayers had a hugely successful run, appearing on every talk and game show (stumping the panelists on What’s My Line?) and making the society rounds. But a new sense of environmental responsibility made wearers start to question the wisdom of tossing their clothes at the end of the day, and the paper-clothes frenzy was finished by the 1970s. The Bayers shifted their attentions to medical garments: The legacy of disposable clothing lingers in surgical shoe covers and the flimsy paper gown now issued in every doctor’s office.

“We knew which side our bread was buttered on,” Audie Bayer says of her company’s forced exit from the world of fashion. “But it was fun while it lasted.”

The Asheville Art Museum presents Groovy Garb: Paper Clothing from Mars Manufacturing Company from Friday, July 13, through Oct. 7 and Living by Design: Mid-Century Modern from July 13 through Oct. 28. Opening reception for both shows (free with museum membership or admission) is July 13, 5-8 p.m. 253-3227.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.