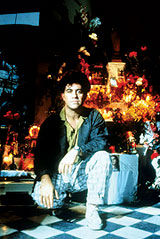

Pedro Almodovar on the set of The Law of Desire, which will screen in the second week of a two-week series showcasing eight of the Spanish director’s films.

|

Christmas comes early this year with Sony Classics bringing us Viva Pedro, a bright, colorful package of eight movies by Spanish filmmaker Pedro Almodovar. The films — ranging from such long unseen early works as Matador (1986) and The Law of Desire (1987) (both of which feature a very young Antonio Banderas) to his most recent films like Talk to Her (2002) and Bad Education (2004) are being shown over a period of two weeks at select theaters around the country. We’re fortunate to be on the list of playdates — the series starts Friday, Oct. 6 at the Fine Arts Theatre — because a better way to spend two weeks of moviegoing, I cannot imagine.

Yes, the films are subtitled and, yes, they come under the vague heading of “art house fare” (as much because they’re subtitled as anything else). But don’t let that stop you. If you do, you’re cheating yourself out of some of the best movies of the past 20 years by one of cinema’s true modern masters. Be warned, however, that Almodovar’s films are unabashedly over-the-top in terms of content — three of them are rated NC-17 with everything that implies and more. They are not for the easily offended.

The official line about Almodovar insists that he is the most acclaimed Spanish filmmaker after Luis Bunuel, and that’s true enough, but it doesn’t take into account the fact that the expatriate Bunuel only made one film, Tristana (1970), in Spain, while all of Almodovar’s films are homegrown. Of course, Bunuel’s films would have largely been unthinkable in Franco’s Spain, while Almodovar’s work is part and parcel of the cultural rebirth of post-Franco Spain. Almodovar’s films could never have existed under Franco — nor, for that matter, could the outspokenly gay Almodovar himself have been able to.

The Bunuel connection also establishes a link between the two filmmakers that is at once apt and deceptive. Both filmmakers have a penchant for the surreal, both tend to favor stories that veer toward melodrama, and both evidence a propensity to be irreligious. But Bunuel is more impenetrable than Almodovar, who is both more of a populist and humanist filmmaker. Almodovar’s films need to be thought of in much the same manner as those of Jean Renoir, whose famous statement, “Everyone has his reasons,” informs his entire output. Almodovar has similarly remarked, “The characters in my films are assassins, rapists and so on, but I don’t treat them as criminals, I talk about their humanity.” This is central to any understanding of Almodovar’s work on a thematic level.

It’s a mistake, however, to think of Almodovar as some kind of ueber-serious, dour filmmaker whose work is oppressively heavy in any sense. Far from it. Almodovar’s films are among the most playfully creative and funny ever made. Despite the richness of thematic material in them, they are first and foremost meant to be entertaining and fun. Rolling Stone movie reviewer Peter Travers once said that Almodovar “is the movies,” and that’s very much the case.

Almodovar’s films are very much movie movies filled with color and spectacular moments that revel in the sheer joy of moviemaking. Things that happen in his films are invariably glamorized into the fabulous a la Hollywood filmmaking with its most unreal “all in glorious Technicolor” form. In Matador, for example, a woman can’t just run down the stairs, she has to have a trailing red scarf and be seen from dazzling angles and glimpsed through the cut glass on an ornate elevator. It’s a pure movie moment in a film full of such things. Sometimes these moments can be taken at face value. At other times, they become subversive statements, as in a scene in the same film where Almodovar’s camera lingers on the crotches of the young men training to be matadors — a slyly satirical scene that would pass without comment were the focus on jiggling breasts. If it makes some viewers uneasy, well, that’s the point.

At bottom, Almodovar’s movies are gloriously outrageous, unashamedly melodramatic soap operas — amped to a spectacular degree. They’re the kind of thing that revisionists (rightly or wrongly) keep insisting Hollywood director Douglas Sirk made in the 1950s — trashy stories that subvert the very genre that contains them. But in Almodovar’s case, there’s no need for a revisionist reading. All the evidence is right there on the screen. It’s a world full of gay filmmakers with busty movie-star transsexual sisters and oddly sympathetic psychotic stalkers (Law of Desire). Boy meets girl can be redefined in terms of attempted rape in a story involving serial killers, religious fanaticism, E.S.P. and a would-be bullfighter who faints at the sight of blood (Matador). In Almodovar’s cinema, the movie proper can stop (and even change format) to include a 20-minute silent movie (Talk to Her). Is it art? Well, if it isn’t, it’s what art should be.

Do not miss this opportunity to see these films in newly struck prints as they were intended to be seen — on the movie screen. It’s the sort of thing that doesn’t come along very often.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.