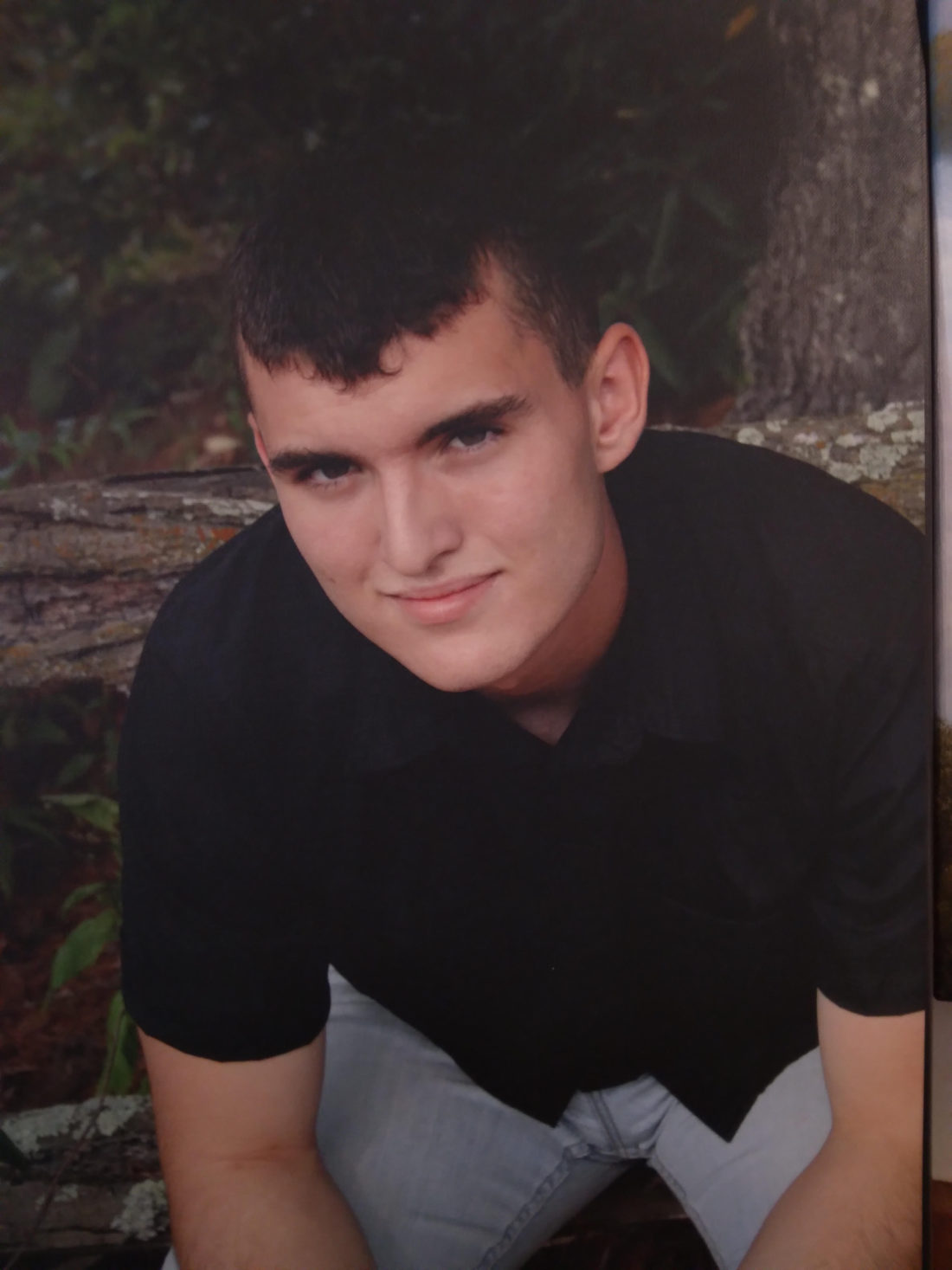

Patti Best describes her youngest son, Jared Best, as thoughtful, talented and highly intelligent. Following his older brother into the Army, Jared served with distinction in Iraq and Afghanistan before returning home to Haywood County in 2014.

However, the toll of combat and the physical harm caused by close contact with explosive devices left Jared with a severe case of post-traumatic stress disorder. On Dec. 31, 2016 at the age of 26, Jared died by suicide with a firearm.

“He was so levelheaded, so steady,” Best tells Xpress. “Jared is someone that we would never in a million years have thought would’ve ended his life. It’s something that we will never totally recover from. Implosion is the word that comes to mind.”

According to data collected by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, North Carolina reported 181 reported veteran suicides in 2019, and firearms were used in 76.2% of those incidents.

Yet the usage of firearms in deaths by suicide extends beyond the veteran community: North Carolina experienced 1,322 deaths by suicide in 2019, of which 799 (59%) involved firearms. That same year, the United States experienced 45,861 deaths by suicide, of which 23,283 (50.8%) involved firearms.

Asheville Police Department’s crime analysis supervisor, Douglas Oeser, shared with Xpress that the department reported 37 suicides and 127 suicide attempts since 2016. Firearms were involved with 12 of the total incidents.

Preventive measures

“Easy access to a gun is often what makes the difference between someone feeling depressed and hopeless for a while, and someone who ends up dead forever,” says Jeffrey Swanson, a professor in psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the Duke University School of Medicine.

In addition to access to firearms, other risk factors for death by suicide are “drugs, having prolonged stress like bullying, a relationship breakup, unemployment, divorce, financial crisis [and] a history of child abuse,” says Sarah Cothren, N.C. associate area director for the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention.

Eleven states have legislation about locking firearms, according to the Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence. North Carolina is not one of them.

Capt. Joe Silberman of the APD encourages gun owners to lock up their firearms. “We give away gun locks as part of Project Child Safe, though I personally recommend some kind of gun safe,” he says.

He notes that APD can also provide literature about deterring access to guns to at-risk people. For example, Project Child Safe, a project of the Firearm Industry Trade Association, recommends the temporary off-site storage of a firearm if an individual in the home is at risk for suicide. “Simply hiding a firearm is not secure storage and poses a risk,” Project Child Safe notes.

The Charles George Department of Veteran Affairs Medical Center in Asheville also provides gun safety locks, as well as suicide prevention coordinators and case managers who can offer support, counseling and other services.

Nationwide, the VA is promoting the safe storage of firearms within the veteran community. On Sept. 17, the agency released a campaign stating “a simple lock puts space between a thought and a trigger.” In testimony before Congress on Sept. 22, Dr. Matthew Miller, executive director of the VA’s Suicide Prevention Program, addressed lawmakers’ concerns about potential infringement of legal gun owners’ rights and underscored the campaign is a public health intervention.

“We are not gearing any campaign or messaging towards restriction,” Miller told Congress, as reported by Military Times. “We are gearing our messaging and campaign towards safety, time and space between a person, a firearm and ammunition.”

Warning signs

The U.S. Department of Justice suggests “extreme risk protection order” legislation — sometimes called “red flag laws” or “gun violence restraining orders” — as another potential tool for the prevention of firearm suicides. The specifics of ERPO legislation varies by state, but they generally empower law enforcement and/or a family member to acquire a temporary court order to remove firearms from an at-risk individual.

Swanson, the Duke psychiatry professor, participated in a research team that examined the effectiveness of ERPO laws in Connecticut and Indiana. In studies published in 2017 and 2019, the team concluded for every 10 firearm removal actions, one life was saved through an averted death by suicide.

“Gun violence prevention advocates and mental health stakeholders need to come together and work to pass laws like risk protection orders,” Swanson tells Xpress.

Nineteen states and the District of Columbia have ERPO legislation, according to Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence. In 2019, Rep. Marcia Morey, D-Durham, co-sponsored HB454 in the N.C. General Assembly to establish ERPO legislation. Morey tells Xpress, “I have seen, being a former judge in Durham, many times witnesses after a shooting say, ‘I knew this was going to happen.’ The warning signs were there.”

The bill empowered a family or household member and a law enforcement officer or agency to petition a district court to remove firearms following “an allegation that the respondent poses an imminent danger of physical harm to self or others by having in his or her care, custody, possession, ownership, or control a firearm.”

HB454 died in the House Rules committee. Paul Valone, president of Grass Roots North Carolina, stated in NC Health News when the legislation was introduced that it lacked due process protections for gun owners, saying, “I challenge you to find any other constitutionally protected right that can be taken away without due process.”

Morey says that allegation is inaccurate, as the legislation requires the gun owner to be notified of the hearing in which the ERPO may be issued. “There is total due process,” she says. “If there’s no factual basis and the judge says this doesn’t rise to the level of removing a gun, a judge wouldn’t do it.”

However, Best, who lost her son to death by suicide, believes ERPO laws might dissuade at-risk individuals from seeking help for mental health issues. “Our oldest son said that the reason that he never talked to anyone when he was coming out of the service about his PTSD symptoms was because he was afraid his guns would be taken from him,” she says.

Best believes that the military needs to prioritize mental health care for veterans, such as treatment for PTSD. “Our government is perfectly happy to send them to war — then just totally forget about him when they come home,” she says. “You need to beat down the doors of whatever agency to get help for your son or daughter.”

You can reach The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline 24/7 at 800-273-8255 for free, private help and assistance finding local counseling. You can reach the Veterans Crisis Line 24/7 via online chat or by texting 838255.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.