Some cinematic solipsists have stated that we are living in the midst of a horror renaissance, simultaneously a golden age of experimentation as well as a revival of the core values of a genre which fell into decline following the slasher glut of the late ’80s. I have often differed with this position, citing the overreliance on jump scares and profligate CG monstrosities that seem to be the hallmarks of the postmodern horror film, while opining the lack of originality and general laziness in screenwriting that seem endemic in a genre for which I have always held the deepest affection. As the summer movie season draws to a close, I have seen precious little that would dissuade me from my perspective on the matter. However, I am pleased to say that Don’t Breathe has encouraged me to reexamine my contentions.

While it must be acknowledged that a single film cannot redeem an entire genre, I will say that Don’t Breathe has engendered a cautious optimism regarding the potential of contemporary filmmakers to craft taught, suspenseful tales on a shoestring budget without falling prey to the unfortunately common shortcuts and shortcomings previously noted. It’s particularly poignant that the filmmakers responsible for my renewed hope are writer-director Fede Alvarez and co-writer Rodo Sayagues, the duo behind 2013’s Evil Dead remake, a movie that is frequently referenced in arguments supporting the aforementioned renaissance. That’s also a film for which my feelings might generously be described as lukewarm, especially in comparison to the vastly superior original. So when I begrudgingly acknowledge what these two have accomplished with Don’t Breathe, it’s not without an admittedly slight smile on my face.

Make no mistake, Don’t Breathe is a film with a particularly warped sensibility, but this is entirely appropriate to its genre and subject matter. What’s particularly laudable about the film is that none of its perversity seems forced or exploitative. Alvarez establishes more character and expository context with his camera in the first five minutes than many films do in the entire first act. While none of the cast’s motivations are explored in great depth, their decisions seem reasonable (if not entirely rational), grounding the story’s more extreme elements in a solid narrative foundation. The premise is relatively straightforward, but the permutations of the plot are far from what you might expect.

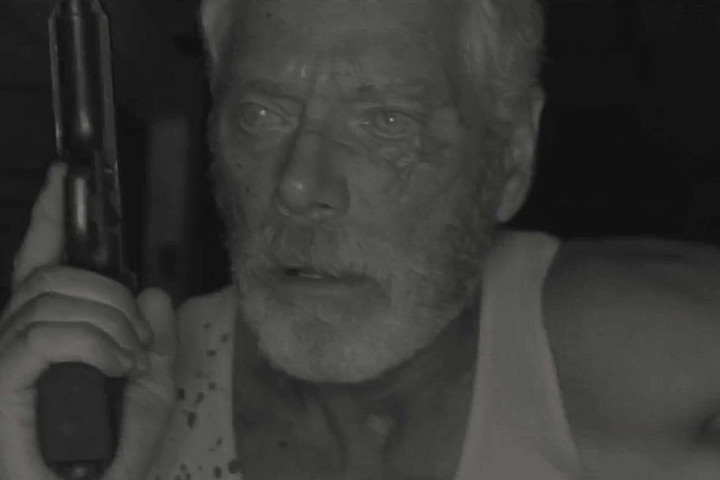

Alvarez is developing into a consummate stylist — with some gimmicky night-vision shots working far better than they should — but it’s his sense of directorial restraint that really places this film on a higher level than his previous work. Alvarez also makes some excellent decisions with his cast, putting together a team of up-and-coming genre stalwarts who rise to the challenges of this claustrophobic chiller’s dialogue-light, performance-reliant script. Dylan Minnette and Daniel Zovatto ably support Jane Levy, with easily her best performance to date, in the lead. But it’s Stephen Lang who steals the show as The Blind Man, a suitably menacing role that establishes Lang as far more than the competent background player he’s been relegated to for most of his career.

This film is by no means perfect, but when it works, it works. It’s not for everyone, but devoted enthusiasts of psychological horror will find the film more than worth their time. It’s not quite as brutal as Green Room (2015), a similarly unrelenting (and similarly great) sadistic thriller with an equally anarchic tone. But Don’t Breathe knows how to use the threat of violence to its greatest advantage. By avoiding the prolific gore that characterized Green Room, it makes room for the development of tension in a way that never really lets up until the final scene. Don’t Breathe plays something like a role-reversed Wait Until Dark (1967), with its antagonist’s disability becoming an almost superhuman threat to our protagonists’ aims (and lives) and Lang’s performance imbuing the Monster of the piece with some sense of pathos — at least until we find out what he’s really hiding in his locked basement.

While I certainly wouldn’t describe Don’t Breathe as a subtle picture, there’s a sense of understatement that differentiates it from the torture porn and Grand Guignol gore that have become the defining characteristics of the postmodern horror picture. If anything, this film is attempting to inject a decadent genre with aspects of Artaud’s Theater of Cruelty and, in trying to do so, give it a new lease on life. Predictable in some places and straining credulity in many others, it nevertheless delivers thrills and chills without succumbing to cheap diversionary tactics. Don’t Breathe breathes new life into a genre that has always seemed preternaturally predisposed to quick stagnation. Rated R for terror, violence, disturbing content and language including sexual references.

Now playing at Carolina Cinemark, Regal Biltmore Grande, UA Beaucatcher, Epic of Hendersonville

I too hope that this movie provides more roles for Lang. But otherwise, I thought it pandered to its audience to an almost obsequious degree, ending pretty much the way I expected it to, although I kept hoping for an alternative right to the end. Can there really be a horror movie renaissance when filmmakers try so hard to make their audiences happy? I suppose a lot of my problem with the film was my loathing of the invading trio. I had a hard time wanting anything to work out well for any of them, even with their mark’s secret proclivities.