Though it is often given short shrift these days — and Browning is often vilified — it’s not going too far to say that Dracula is the true granddaddy of the horror film. It was the first talkie horror movie, and it provided the template for nearly everything that was to come after. Had it not been a success, the history of the genre would have been very different indeed. Historically speaking, it is perhaps the most important horror picture ever made. The argument today is that it’s slow, that its horrors are very reticent and that after the first 20 minutes, the film becomes little more than a replica of the 1927 play that brought Lugosi to prominence in the first place. Well, the film isn’t exactly fast-paced, and its horrors are certainly more suggested than stated. The first 20 minutes are the most effective, but the rest is not without merit — and it really isn’t that much like the play. What the film’s detractors fail to see — apart from the undisputed value of Lugosi’s performance — is that the entire film is bathed in an atmosphere of nightmare, dread and otherworldliness that is unlike anything else in American horror cinema. While subsequent 1930s horror films are undeniably better and certainly slicker, nothing else captures the strange funereal poetry of Dracula — and the equally otherworldly performance of its star.

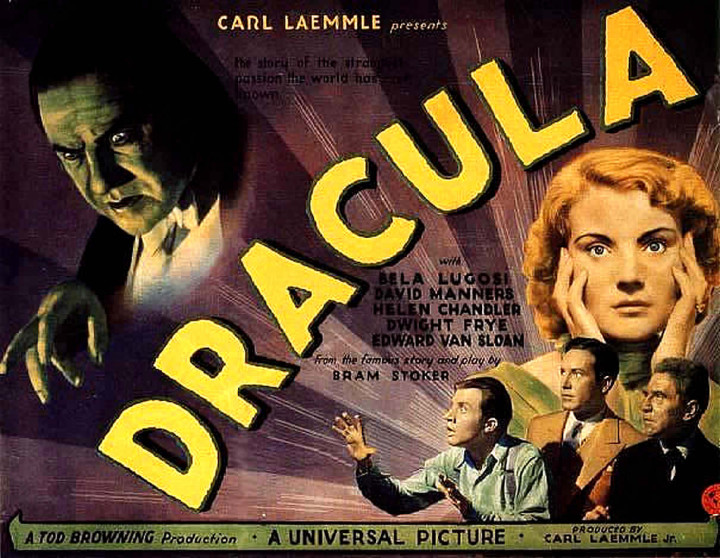

Dracula is significant in several ways. It’s not just the first talkie horror film, but it’s only the second vampire movie ever made (and the first American one). Beyond that, it’s one of the first American-produced films that takes the supernatural seriously and doesn’t come up with some half-cocked “rational” explanation that’s usually harder to believe than the supernatural. No, this is the goods. It’s hard now to realize that the whole idea of vampires — as anything other than seductresses after a wealthy man — was not a common idea in 1930 when the film went into production. Universal, themselves, were none too sure of what to do with the film. The early advertising, though horrific in imagery, kept the word “vampire” at bay and went with “The story of the strangest passion the world has ever known.” Well, I suppose that’s fair enough.

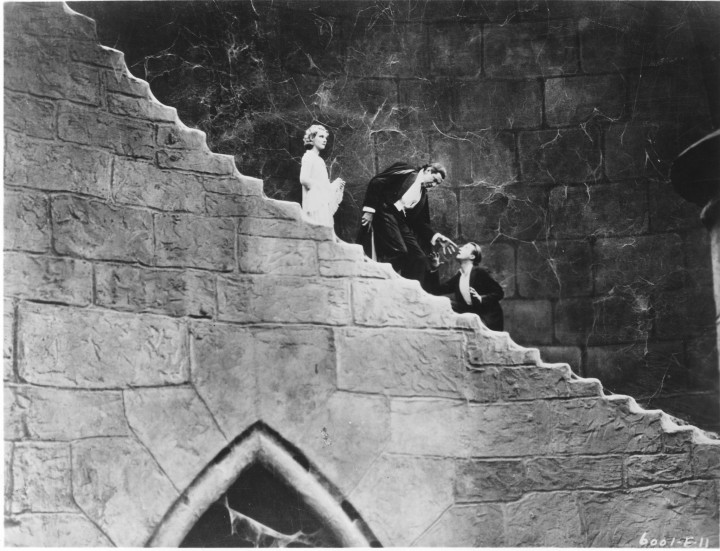

There’s no denying that the film’s first 20 minutes are its best. The evocation of a nightmarish Transylvania swathed in mist and mystery simply could not be better. The enormous, oppressive, even crushing architecture of Dracula’s castle has never been touched by any version of the story. Browning’s otherworldly vision of a crypt in which fog seeps right out of the earth remains unsettling after 80 years, as does his somewhat improbable collection of wildlife (Carpathian armadillos?) that wanders the less inviting parts of the castle. The Borgo Pass midnight meeting, with Dracula playing a very startling coachman for his guest, remains a shuddery piece of filmmaking.

However, the idea that the film grinds to a halt once it hits England is just demonstrably untrue. The first scenes in London haven’t the gothic power of the opening, but there’s nothing wrong with them — some of them are even surprisingly fluid — and they have their own appeal. Once it gets to the drawing room, things do slow down (though there’s actually very little of the play in these scenes), but it’s hard to overlook such prime horror movie moments as Dracula smashing the mirrored cigarette box and the duel of wills between the Count and Van Helsing. And really, why would you want to? These are iconic moments in horror cinema. While the film has some clunkiness to its construction, it does lay down the basic outline for Universal horrors of the 1930s. In fact, the next year’s The Mummy is virtually the same story and structure, but with a different monster and a lot of the bumps smoothed out. (That’s not surprising, since 1932 was the year where the movies and sound finally worked out their differences.) It is, however, a mistake to view Dracula as stodgy or unsophisticated in its use of sound.

A great deal has been written over the years — and often by otherwise sensible people — about the film’s lack of a musical score and how it hurts the film. I don’t agree. First of all, the lack of a musical track is not strictly speaking a by-product of early sound recording. Frank Borzage’s Liliom (1930) has a score (and a surprisingly effective one). But that aside, there are a number of horror films as late as 1933 without a score. Dracula hardly needs singling out in the matter, and, frankly, I think it’s perhaps the only horror film that benefits from the lack of one. The eerie stretches of complete silence only enhance the film’s atmosphere. People seem to forget that one of the things the talking picture did was give the filmmaker mastery over the soundtrack. With pianists, organists and even small orchestras accompanying silent films, there was no such control. Talkies actually allowed filmmakers to use silence for the first time. That unearthly dead-of-night silence that accompanies Dracula’s attacks on his victims is chilling in a way that a score could not convey nearly so well.

Moreover, the sound in Dracula is occasionally more than simply a case of recording the dialogue. The entire sequence involving the examination of the dead ship that brought Dracula to England is done through the soundtrack. I’m sure this was partly an economic decision, since it cut down on the cast and required little in the way of sets, but it’s still a striking use of sound. It’s also a scene that has a terrific visual payoff when the hatchway is opened to reveal the grinning, insane Renfield (Dwight Frye) — and his trademark laugh — standing at the bottom of the stairway with the lines of the rails converging like a spider web.

Today it’s become quite the fashion to use the Spanish-language version of Dracula — filmed on the same sets with a different cast and director (George Melford) at night — as a cudgel against the Browning version. This is based almost entirely on the fact that George Melford makes some really clumsy attempts at traveling shots and shot the script as it stood. The latter is interesting in that it explains why the first time we see Van Helsing he appears to be at a laboratory in the Carpathian mountains. And more notable still, it includes Van Helsing and Harker disposing of the vampire Lucy, which also explains why they’re wandering around outside to see Renfield going to Carfax Abbey to meet Dracula. Browning either never shot those scenes, or they were cut somewhere along the way.

The absence of those scenes does make the continuity in the Browning version awkward, but it seems a small price to pay for other trade-offs, like the vampirization of Renfield by Dracula in Browning’s rather than leaving it to the three vampire wives as the script had it and as Melford shot it. Browning is not only closer to Stoker’s intention, but he gives (as does Stoker) the proceedings an element of subtext. There’s also the scene where Renfield crawls over to the maid who’s lying unconscious on the floor. Browning leaves this disturbingly vague, while Melford turns it into a gag where we see that the object of his interest isn’t the maid at all, but a spider. Of course, the biggest thing that Melford doesn’t have is Lugosi. No, he has Carlos Villarías, who not only has the grave misfortune of looking like Topo Gigio, but is apparently of the eyes-and-teeth school of acting, since he’s always as wide-eyed as possible and appears to be advertising for the quality of some toothpaste. But really, it’s the fact that it’s just not Lugosi — and for some of us, if it’s not Lugosi, it’s just plain not Dracula.

The Thursday Horror Picture Show will screen Dracula Thursday, Oct. 2, at 8 p.m. in Theater Six at The Carolina Asheville and will be hosted by Xpress movie critics Ken Hanke and Justin Souther.

Why is Tod Browning vilified? (aside from the fact that he uses real deformed people in FREAKS). I thought that the rediscovery of many of his Lon Chaney silents (especially THE UNKNOWN) had helped to restore his reputation.

You’re right about the lack of a music track. The sound effects in the Castle Dracula sequence alone justify that not to mention setting up the famous “Listen to them, the Children of the Night, what music they make” line. Thank goodness you’re not showing the version with the Philip Glass score.

I could put forth several good theories as to why Browning is vilified — ranging from a certain author managing to give all credit to Chaney for this silents to the fact that another author has systematically tried to denigrate Browning’s work on Dracula in favor of the Spanish version to the simple fact that the silents — and let’s face it, the audience for those is much smaller than the audience for Dracula — are mostly not horror pictures, despite Ackerman making an entire generation think they were. A lot of the denigration centers on Dracula and is grounded in that damned Melford version with all manner of very dubious assertions. The most ludicrous one being that Melford screened the Browning footage and said, “We can do better.” How he screened this footage when some of his film was shot on the same sets before those sets were fully dressed for the Browning film is never addressed. Then there’s the idea that Browning both botched the film and didn’t even shoot most of it. Okay, which is it? It can’t be both. But some of this isn’t new. Wm. K. Everson was taking potshots at him in the early ’70s, saying that his silents weren’t very good, that Chaney was better under other directors, and that if London After Midnight is ever found it will probably be “the nail in the coffin” as concerns the reputation of his Chaney collaborations.

I wouldn’t show the version with the Glass score if you paid me. By the bye, probably the best thing about the Blu-ray restoration — after all, there’s only so much you can do with a movie that’s been constantly reprinted for 83 years — is that the soundtrack has been cleaned up. Of course, that makes it the sixth Universal has gotten me to buy the movie — and if they ever find the curtain speech they’ll make it seven.

I’m guessing the first author is Michael F. Blake who doesn’t count for much in my book but who is the other? Surely not David J. Skal (why do all these authors have middle initials?) who co-wrote DARK CARNIVAL which I remember as being pro-Browning although it has been many years since I read it. As for the Melford story, this from the man who gave us Valentino in THE SHEIK? . Right.

Actually, you’re right in both cases. And your assessment of the first one strikes me as generous. As for the other, somewhere along the way, David seems to have taken against Browning — and it seems to be tied to the Topo Gigio Dracula. The business of the middle initial…who knows? Maybe it’s a desire to emulate Bill Everson, whose own middle initial was a complete fabrication. Seems he liked the way William K. Howard flowed so he copped the “K,” having no middle name himself.

Actually I’m generous to a fault. You despise Michael F. Blake (understandably considering how smug and self-righteous he is) whereas I simply just plain don’t like him.

Sorry to hear that Skal has changed his tune but considering how clever he thinks is in some of his recent DVD commentaries, I’m not all that surprised. Now I’ll have to dig up a copy of DARK CARNIVAL and see what it actually says.

Did not know that about Mr Everson but he was right. William K. does sound more impressive.

“There are far worse things …. Awaiting man… Than Death ….”