I don’t know if I’ve ever loved anything as much as Leon Vitali loves Stanley Kubrick. Don’t get me wrong, I do love Kubrick — enough that I devoted an entire summer semester in college to a class that pored over every inch of extant film that the man ever shot — but given the opportunity, I doubt I could have turned over my entire life to helping him realize his creative vision. That’s exactly what Vitali did, and with Filmworker, documentarian Tony Zierra has finally given Kubrick’s unheralded right-hand man his much belated due.

For a filmmaker about whom so much has been written, little has been said about the incalculable contributions Leon Vitali made to every Kubrick film from The Shining onward. Since this is Kubrick, that means only three completed films, but it also means that attending to the director’s obsessive needs was a 24-hour-a-day job. Sure, I was familiar with Vitali’s story, at least in passing — an up-and-coming young British actor who landed a dream gig as the closest thing Barry Lyndon had to a villain, only to give up his promising career to become Kubrick’s personal assistant — but it turns out I didn’t know the half of it. Zierra delves into Vitali’s personal and professional narrative to such an extent that his centrality to Kubrick’s work is beyond doubt, and his story is both heart-wrenching and inspiring.

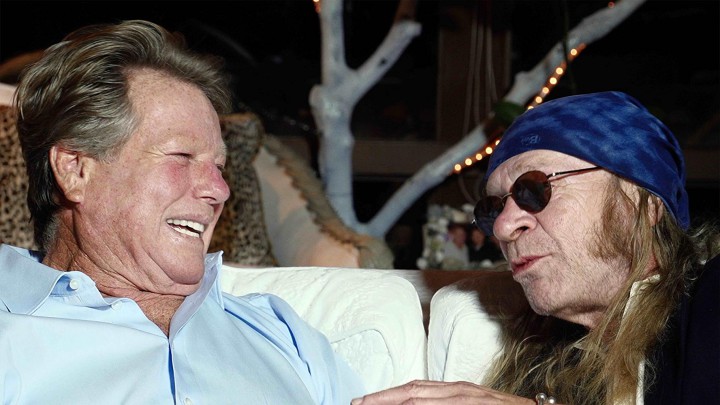

Now in his late sixties, haggard and world-weary, Vitali wouldn’t look out of place on stage with The Rolling Stones. Hearing him describe falling in love with Kubrick’s work on seeing A Clockwork Orange or the rare approval he received from the director for his work as Lord Bullingdon in Barry Lyndon, one gets the sense of a widower recalling a dearly departed spouse. And in many ways, Vitali’s relationship with Kubrick was closer than even that, with Vitali’s children describing their father sleeping fully clothed on a doormat so that he wouldn’t sleep through an emergency call from his lord and master.

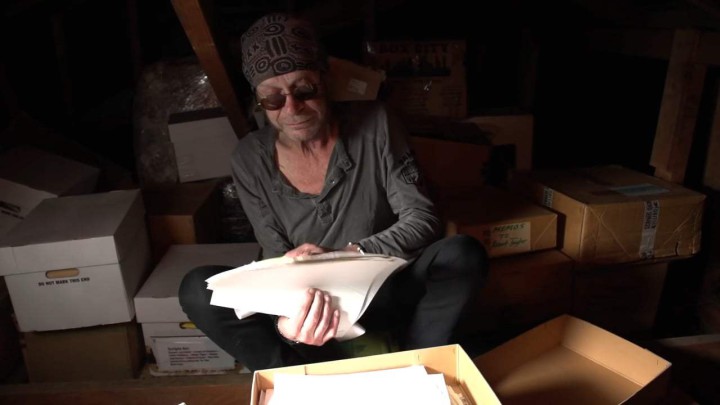

Vitali’s devotion to Kubrick is indeed cultish, but the relationship wasn’t entirely one-sided. Under the auspices of his role as Kubrick’s go-to fixer, he filled the role of half a dozen production executives, handling everything from location scouting to casting to foley design to coaching first-time performers like Danny Lloyd and R. Lee Ermey. But he was also designing surveillance systems that allowed Kubrick to monitor an ailing cat and fielding angry responses from studio executives who had received demanding letters penned by Kubrick but signed with Vitali’s name.

If Vitali’s dedication to Kubrick sounds unrewarding, his life after the filmmaker’s death is downright criminal. Functionally broke after years of service to one of the greatest auteurs to ever live, Vitali has been reduced to borrowing from his kids because nobody in Hollywood will hire him, despite his mind-boggling skill set. When LACMA organized a Kubrick retrospective, nobody bothered to call him — but ever the acolyte, he led dozens of tours of students and industry bigwigs through the exhibit anyway. And that’s a perfect metaphor for Vitali’s work — self-sacrificing and utterly devoid of ego.

When I got the chance to program the premiere of Filmworker as a part of the Asheville Film Society’s June schedule, I jumped at the chance without having seen the movie. Having watched it, I couldn’t be more confident that Vitali’s story deserves as broad an audience as possible. I had initially considered showing Filmworker as a double bill with Barry Lyndon, but it might make a more appropriate counterpoint to Rodney Ascher’s Room 237, a film that mythologizes Kubrick almost to the point of absurdity. If Room 237 examines the cult of Kubrick, Filmworker comes across as the confession of that cult’s high priest. By focusing on Vitali himself and never claiming to delve into “the real Stanley,” Zierra’s documentary provides more invaluable insight into the genius — or madness, depending on your perspective — of Kubrick than any other film on the subject. Not Rated.

One screening only, Tuesday, June 5 at 7 p.m., presented at Grail Moviehouse by Asheville Film Society curator and Xpress critic Scott Douglas.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.