Even though Little Men and Morris from America were edged out by Don’t Breathe for Pick of the Week, they are both every bit as good as that film. But being confronted with two exceptional yet substantially different films focused on the struggles of male adolescence, choosing one or the other would have been nearly impossible. So the fact that Don’t Breathe was selected has more to do with that film’s very different subject matter than any real edge in quality or emotional affect. I mention this because some moviegoers may be better served by Morris or Men, or both.

Little Men is a small film in the best possible sense, focusing on palpable emotional stakes at a human scale, with no punches pulled. It’s one thing to talk about wealth disparity and gentrification as social ills, another still to watch these issues tear apart the friendship of two boys powerless in the face of overwhelming economic odds. The film views its principal conflict through the lens of two 15-year-old boys whose parents become embroiled in a fiscal feud. And in recontextualizing the disagreement into a look at its impact on two young men who can scarcely understand it, much less influence its outcome, writer/director Ira Sachs has made the issue at once more relatable and more appalling.

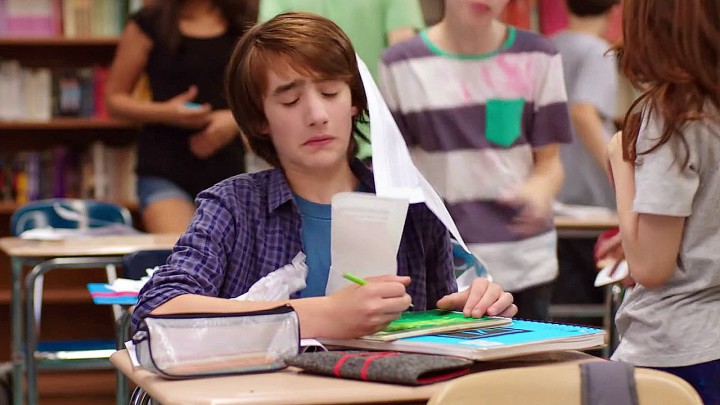

The story follows Jake and Tony, two kids in New York with artistic aspirations, who find themselves in a fledgling friendship after the death of Jake’s grandfather leads his family to relocate from Manhattan to an inherited Brooklyn building where Tony’s mother runs a struggling women’s clothing store. As Jake’s bitchy aunt forces his struggling-actor father to raise the store’s rent, the writing is on the wall for Tony’s mother, Leonor, a Chilean immigrant trying to eke out a living in a rapidly changing economic environment. But the boys couldn’t care less; they’re more concerned with fantasy novels, video games and their dreams of attending the prestigious LaGuardia High School of Music & Art and Performing Arts — Jake as a visual artist and Tony as an actor. It’s only as the rent issue comes to a head that the boys realize their parents’ pettiness could cost them their brotherly bond.

If the story’s conflict seems relatively straightforward, its implications are not. Tony, a charismatic budding thespian with chops to spare, is instrumental in bringing Jake out of his shell and inspiring him to pursue his artistic aims in spite of his innate lack of confidence. The consequences of losing this relationship for the story’s ostensible protagonist are considerable. It would be easy to attribute the titular designation to these “little men,” but that dubious distinction is better worn by the boys’ fathers: Jake’s dad, Brian, an off-broadway actor who lets his psychotherapist wife pay the bills, and Tony’s absentee father working in Africa, whose parental prowess Tony defines as “better when he’s not around.” The lack of strong father-figures looms large over the proceedings, as the boys themselves are easily the most effectual male characters in the film.

Sachs’ humanist leanings are clear, as is his indebtedness to Russian playwright Anton Chekhov, whose drama The Seagull is Brian’s preoccupation for most of the film. Sachs’ direction is heavily influenced by the stage, although his camera movements are more dynamic than those of directors with similar leanings. His greatest strength is his ability to draw exceptional performances from his cast, with Paulina Garcia delivering a standout turn as Leonor, and Greg Kinnear in possibly his best dad-role since Little Miss Sunshine. But it’s the boys who steal the show, with Theo Taplitz as Jake, ably embodying the simmering sensitivity and inherent insecurity of the artistic temperament, and Michael Barbieri blowing his adult costars out of the water with Tony’s superficial exuberance. A scene in which Barbieri dominates his teacher during an exercise in acting class is worth the price of admission alone.

If Little Men has any real drawbacks, they’re that the film is somewhat deficient in the denouement department and that it might lack relatability to audiences without an affinity for, or familiarity with, the New York arts scene. But such quibbling complaints are overshadowed by an understated story and superb performances. Sachs has delivered a poignant and moving human drama, an exploration of the value of friendship and the frustrating powerlessness of youth in the face of an uncaring and ever-changing world. Little Men is not about men but about people writ large, and anyone who qualifies for personhood is likely to find something in this film that will resonate. As far as little films go, this one has a big impact. Rated PG for thematic elements, smoking and some language.

If Little Men has any real drawbacks, they’re that the film is somewhat deficient in the denouement department and that it might lack relatability to audiences without an affinity for, or familiarity with, the New York arts scene. But such quibbling complaints are overshadowed by an understated story and superb performances. Sachs has delivered a poignant and moving human drama, an exploration of the value of friendship and the frustrating powerlessness of youth in the face of an uncaring and ever-changing world. Little Men is not about men but about people writ large, and anyone who qualifies for personhood is likely to find something in this film that will resonate. As far as little films go, this one has a big impact. Rated PG for thematic elements, smoking and some language.

Opens Friday at The Grail Moviehouse

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.