I have to confess to being largely ignorant of Alexander McQueen, the enfant terrible of haute couture at the center of directors Ian Bonhôte and Peter Ettedgui’s new documentary. And in the interest of full disclosure, I was completely convinced that any biographical documentary about a fashion designer would be firmly outside my figurative wheelhouse. My monochromatic uniform could be generously described as boring, and the only direct mention of McQueen I recall crossing my path was something an ex-girlfriend mentioned about Lady Gaga’s shoes, which I promptly filed in the “don’t care” section of my brain. But Bonhôte and Ettedgui have crafted something far deeper, more insightful and visually engaging than my admittedly tempered expectations prepared me for, a remarkably engrossing look at the soul of a tortured artist.

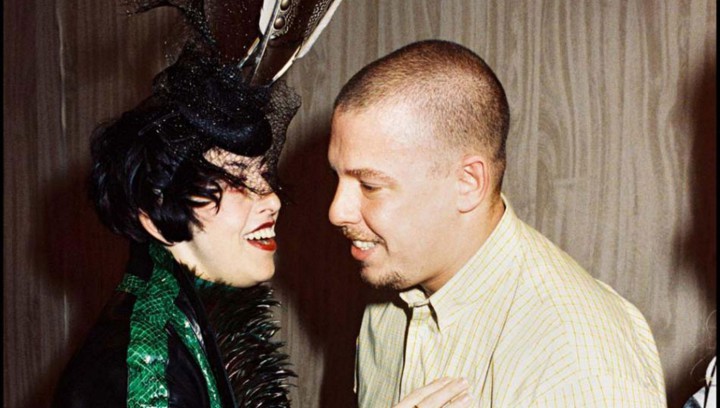

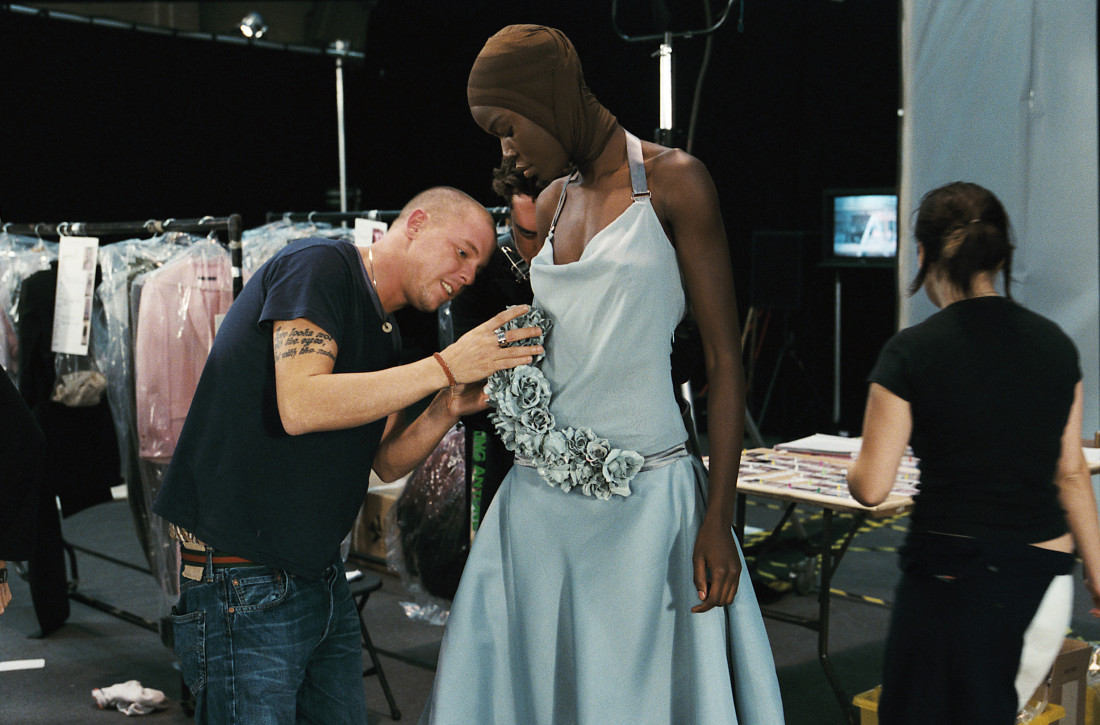

And the emphasis there should be on the word “look,” because McQueen is an unquestionably gorgeous watch. The requisite talking heads are there, but the archival footage of the designer’s confrontational catwalk collections form the true spine of the film. As context is developed from McQueen’s friends and associates, we see his career blossom organically from that of an aspiring Saville Row tailor’s apprentice to the cocaine-addled head of French fashion house Givenchy, with images of the designer’s often staggeringly twisted creations charting the path of his mounting inner turmoil more effectively than the biographical details revealed could possibly elucidate.

And the emphasis there should be on the word “look,” because McQueen is an unquestionably gorgeous watch. The requisite talking heads are there, but the archival footage of the designer’s confrontational catwalk collections form the true spine of the film. As context is developed from McQueen’s friends and associates, we see his career blossom organically from that of an aspiring Saville Row tailor’s apprentice to the cocaine-addled head of French fashion house Givenchy, with images of the designer’s often staggeringly twisted creations charting the path of his mounting inner turmoil more effectively than the biographical details revealed could possibly elucidate.

Those biographical details are present, however, and they paint a compelling portrait of a deeply troubled man whose genius was only equaled by his capacity for self-destruction. We learn of childhood abuse both witnessed and endured by McQueen, and the ramifications it bore on his mental health as an adult. We see evidence of spiraling drug problems, unstable romantic relationships and deeply unsettling personal betrayals. But Bonhôte and Ettedgui avoid the tabloid sensationalism such salacious subject matter might have engendered, instead relating McQueen’s psychological tumult to the creative output his suffering seemed to drive. The resultant impression is one of a complex personality who mined the dark corners of his past traumas to create an utterly unique — and often grotesque — form of beauty. McQueen as a man may have vacillated between monstrous and mundane, but his work found transcendence in horror.

Perhaps there was some benefit to coming in relatively blind for McQueen, as it allowed me to experience the shock and repulsion that the designer was aiming for in his designs with unvarnished surprise. And there was unequivocal benefit to seeing that work displayed on a big screen, where the transgressive imagery and arresting theatricality of McQueen’s creations could be appreciated in a way that simply would not have been possible in a smaller format. While it may not have prompted any deeper interest in the fashion world — a realm which McQueen himself seemed to view with deep disdain even as he strove for its acceptance — I can say that McQueen gave me an appreciation for its subject that I could not have foreseen when I walked into the theater. Rated R for language and nudity.

Now Playing at Fine Arts Theatre.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.