Landing somewhere between art-house and solid mainstream entertainment, Pawn Sacrifice probably owes its art-house cred to its cast, subject matter and screenwriter Steven Knight (Locke), and its mainstream quality to director Edward Zwick. It’s a surprisingly agreeable blending — all the more so because Zwick usually tackles pseudo-prestige pictures of an alarmingly middle-brow nature, and this is neither. I’m not saying it’s necessarily all that high-brow (that may depend on your take on chess), but neither is it your standard mainstream fare. And it is certainly the best thing Zwick has ever done.

The film is a biopic of Bobby Fischer, but its focus is ultimately the 1972 chess match between Fischer (Tobey Maguire — with added facial moles) and Soviet grandmaster Boris Spassky (Liev Schreiber). That’s a perfectly reasonable approach, since that match was a cultural event of some note. I can’t claim to have followed it at the time, but it was impossible not to be aware of it. (My major memory is from the spillover into pop culture — like the bogus ad in National Lampoon with a doctored picture from The Seventh Seal promising, “Bobby Fischer shows you how to beat Death.”) It was somehow transformed from a chess match into a heavily politicized event. This wasn’t just Fischer vs. Spassky. This was the U.S. vs. the U.S.S.R. The idea of a chess match being of such international significance may be hard to grasp 40-plus years on, but it was.

Steven Knight’s screenplay uses the match as both the film’s centerpiece and its underpinning. The film opens in the midst of the match with a grabber scene that is close to incomprehensible outside the context of the film, but one that undeniably captures your attention. From there, the film flashes back to Fischer’s childhood (where he’s portrayed at different ages by Aiden Lovecamp and Seamus Davey-Fitzpatrick), charting his strained relationship with his neglectful, card-carrying communist mother (Robin Weigert), the discovery of his amazing talent for chess, his self-absorption, his desire for solitude — and his complete lack of social skills and his incipient mental problems and paranoia. The film suggests much in these scenes, but spells out little. Is Fischer’s paranoia grounded in his mother using him as a buffer against U.S. agents investigating her political ties? Is his later rabid anti-communist stance an expression of his resentment of his mother? The film says — maybe, but doesn’t pretend to know. That’s a refreshing approach in a “true story” film.

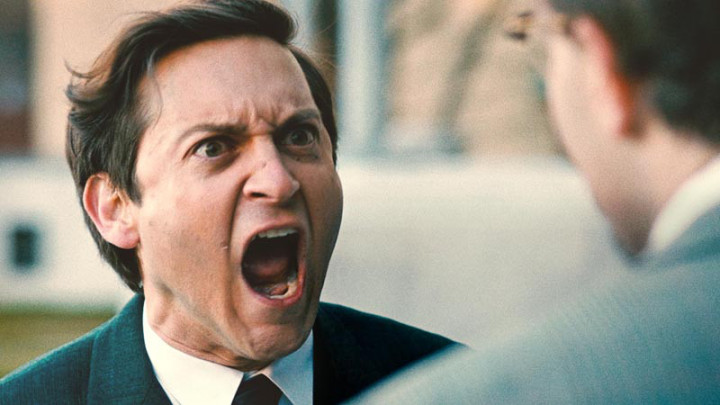

A lot of why the film works lies in the cast. Tobey Maguire truly pulls off the role of Fischer. He captures the man’s genius, his tragedy, but perhaps most importantly what an impossible person he was. It is possible to feel a measure of sympathy for Maguire’s Bobby Fischer. He is very clearly a man trapped in the confines of his own troubled mind, but he is almost never likable. He’s brusque, arrogant and eccentric beyond all reason. It’s no wonder that Spassky thinks his persona is a pose — and at times, it’s possible for us to believe that, too. But if it ever was a pose, it quickly became all too real. Maguire’s performance catches all these aspects and more. Still, he’s not the whole show. Peter Sarsgaard as the Catholic priest chess master who serves as Fischer’s coach (and most concerned friend), and Michael Stuhlbarg as his manager are both excellent. So is Schreiber’s Spassky. In fact, the whole cast — even the smaller supporting players — are at the top of their game.

While I do attribute the film’s near greatness to factors other than Zwick’s direction, it has to be considered. It’s his usual craftsmanlike approach, but it fits here as it has rarely done in the past, and it would be foolish to think that Zwick had nothing to do with the performances. Moreover, it takes more than a little talent — certainly more than a great script and performances — to manage to make chess games cinematically exciting, and Zwick does. The film may just miss greatness, but it’s not far off from it. Rated PG-13 for brief strong language, some sexual content and historical smoking.

Anybody see this one?

I did.

You did? Oh, wait, now I remember.

If memory serves, you were there.

That sounds accurate.

But is it?

Not sure. I need a third party to confirm.

Well, that’s tougher.

It was a wonderful story. Ultimately, Bobby is a man that yearns for the truth but in a world full of lies – what hope can he gain but insanity?