Falling somewhere between Planet Earth and An Inconvenient Truth, Seasons (Les Saisons) is an undeniably interesting amalgam of nature doc and environmental polemic. Moreover, the film itself is a visual masterpiece, as one might expect from the filmmakers behind the 2003 nominee for the Best Documentary Oscar, Winged Migration. Co-directors Jaques Perrin and Jaques Cluzaud have achieved a truly noteworthy accomplishment in the realm of cinematic technique. While I hesitate to call it a documentary in the strictest sense of that term, Seasons more than merits a watch on the basis of its stylistic acumen alone.

However, there’s a lot more going for this film than the remarkable visual experience it offers. It diverges from pure documentary in that it imposes on its subject a rudimentary narrative, a parable tracing its roots back to the end of the last ice age and terminating in the emergence of humanity’s subjugation of the natural world. The protagonist in this story is nature itself — or, more specifically, a western European forest ecosystem and its inhabitants. The result is a diatribe on the deleterious influence mankind has inflicted upon the natural world to which he remains inextricably linked. Although it might seem a bit heavy-handed at first glance, the finished product is profoundly affective and manages to make an important point with a minimum of extraneous soliloquizing on the part of the narrator.

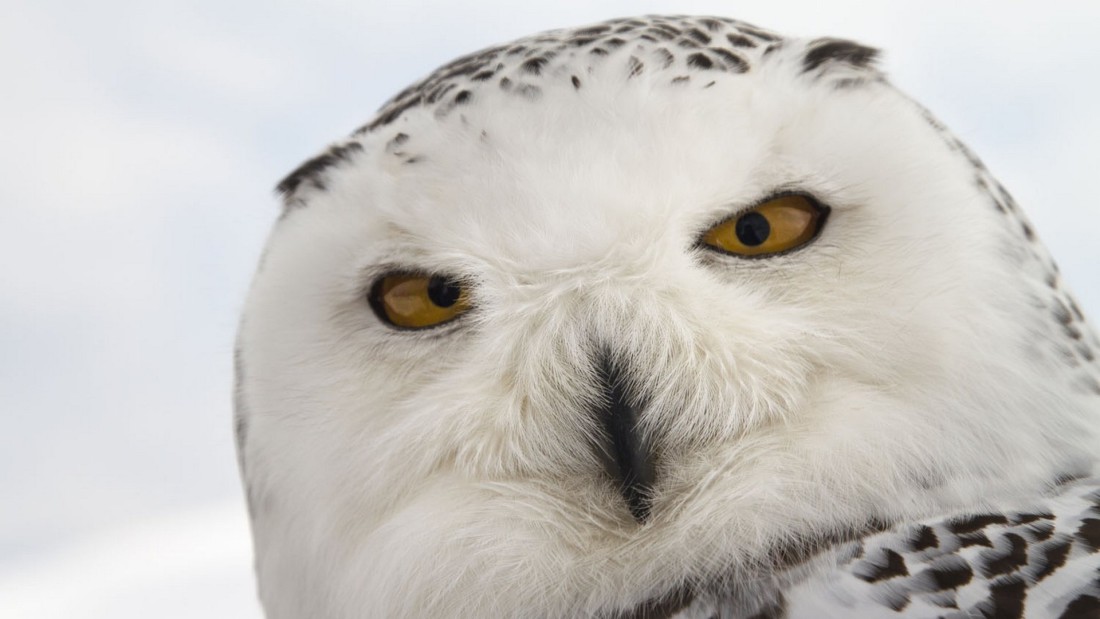

The filmmakers’ extraordinary camerawork follows foxes, deer, wolves, boars — you name it. From the smallest insects to the largest trees, every presence in the forest is a character. This not only creates a showcase for some of the most impressive camera movement and artful CG post-production work ever to grace the screen, but also allows ample opportunity on the part of the audience for psychological projection. Perrin and Cluzaud ably employ advancements in modern filmic technology to capture breathtaking forest vistas of the animals in their native habitats. They also employ traditional cinematic techniques, such as shot-reverse-shot reactions, to impart a sense of personality to the animals themselves. The upshot of all this is, even devoid of any dialogue or human presence for the vast majority of the film, the narrative moves along without succumbing to repetitive monotony.

Seasons does depict the violent struggles of the natural world in a relatively unvarnished light, and animals are shown hunting, killing and eating each other (humans are included in hunting activities late in the film). But rather than indulging in the shock value of such interactions, no gore is displayed, so even small children should be largely undisturbed by the action, provided sufficient context and explanation is provided by attentive parents. This is a film decidedly geared toward engaging families in conversation surrounding conservation and humanity’s role as stewards of the Earth — which can be challenging to explain to younger children if only because the scope and scale of our current circumstances can prove overwhelming even to adults.

It’s this capacity to establish context that proves to be Seasons’ most laudable and least evident accomplishment, saying more with a bit of historical perspective than could reasonably have been conveyed with an excess of environmental evangelism. Yet the importance of the film’s message functions in concert with its visual spectacle, providing an engaging experience that should resonate with moviegoers in all four quadrants. If the film gets a little uglier with its third-act introduction of modernity, that’s by design — centuries of human progress have made the world a significantly uglier place. But the message Perrin and Cluzaud are trying to convey is explicitly stated in the film’s final frames: It’s not too late to clean up the mess we’ve made. Rated PG for thematic elements and related images. French narration with English subtitles.

Opens Friday at Grail Moviehouse.

I was really excited to read your review. For two reasons…

a) I took my 9-year-old daughter to watch this movie, and we both loved it.

and

b) I’m so happy that this movie came to Japan 9 months before it came to the U.S. Usually we get movies here 9 months after they appear in the U.S. I think Japan’s got a special relationship with French cinema.