F.W. Murnau’s 1922 silent horror classic Nosferatu is the granddaddy of all vampire pictures. An unauthorized adaptation of Bram Stoker’s Dracula, Nosferatu was a key work in the development of the horror film and one of the few silent horror films that still manages to be utterly chilling. (Nosferatu was so unauthorized, by the way, that Stoker’s widow succeeded in getting a court order to have all copies of the film destroyed; thankfully, not all were.) No one who has seen the film — or even stills from it — has ever forgotten the chilling image of Nosferatu’s concept of the vampire. So striking and so inhuman is that image that Nosferatu is also a film that has always been surrounded by an air of mystery concerning the identity of the actor playing the character of Count Orlok, the vampire. The very name of the actor, Max Schreck, seemed unlikely as a real name, since Schreck is derived from the German word for terror. Rumor long persisted that the role was performed by noted German actor Alfred Abel under a nom du cinema.

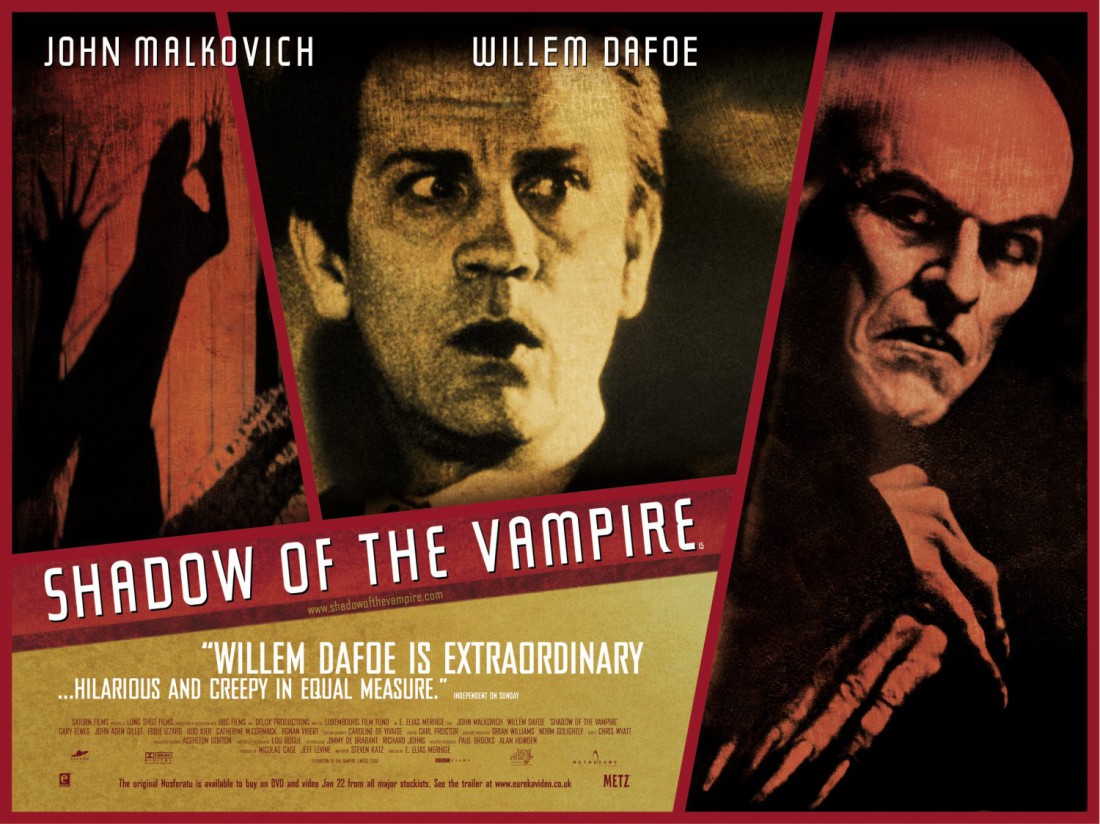

The basic premise of Stephen Katz’s script for Shadow of the Vampire is that Schreck was nothing more nor less than a real vampire with whom Murnau managed to strike a bargain — namely, the blood of his co-star, Greta Schroder (Catherine McCormack), with whom the creature had become infatuated — to star in his pioneering “symphony of terror.” It’s a fascinating conceit, but one that in lesser hands might have become little more than a mildly diverting, shaggy bloodsucker story. Here, however, director E. Elias Merhige and a stunning cast take Katz’s visionary imaginings of the making of Nosferatu and create a completely satisfying and compelling work that is part horror film, part biopic, part artistic credo, and all brilliant. As presented in the film, Murnau (John Malkovich) is every inch the driven genius (“If it’s not in frame it doesn’t exist!”) we’d expect the maker of a startling series of artistic successes such as The Last Laugh, and Tabu to be. A brilliant and seemingly tormented artist, Murnau himself was something of a mystery: Openly homosexual in a society that didn’t accept such an idea, Murnau managed to attain both commercial and critical success right up to his untimely (and scandalous) death in a car wreck in the Hollywood Hills in 1931.

Whether or not Malkovich’s Murnau is exactly correct historically, he conveys the essence of the man who very well could have made those phenomenal films. Malkovich’s Murnau is matched every step of the way by Willem Dafoe’s uncanny portrayal of the obviously fictionalized Max Schreck. In some ways, this is the easier performance, since the character is made from whole cloth. Dafoe’s portrayal, however, is startling in that it is at once terrifying, menacing, comic, and, on occasion, strangely moving. (It is no mean feat to generate sympathy for a character so unholy-looking as Schreck!) The idea that Schreck is a real vampire also allows for a somewhat different take onwhy Murnau chose to shoot his film in largely real locations at a time when everything in German film was studio created. After all, it’s easier to go to the vampire than to have the vampire come to Berlin. This offers the added bonus, though, of making Murnau and his cast and crew embark on a journey into a land of phantoms much like the one the characters in Nosferatu experience. One of the best remembered titles from Nosferatu reads, “And when he crossed the bridge, the phantoms came to meet him.” Surely it is not by accident that Murnau and company embark on their excursion in a train with the name “Charon” — i.e., the ferryman who takes the dead across the River Styx in mythology — emblazoned on the engine.

A deeply complex film, Shadow of the Vampire may slightly falter toward the end, with a climax that — while brilliant — is a little too contrived. Plus, it takes the film way past the realm of alternate reality. However, it is a truly brilliant horror film about a horror film. Shadow of the Vampire is also utterly unique, marked by stunning wide-screen photography by first-time cinematographer Lou Bogue. Apart from an ill-chosen reference to Sergei Eisenstein (in a story set two years before anyone ever heard of Eisenstein), the period is expertly captured — from the hedonistic decadence of post-WWI Germany to the artistic aims of German film — in this fantasticated imagining of the making of a real film. Sometimes the fantastic seems more real than reality, and that’s the case here.

The Thursday Horror Picture Show will screen Shadow of the Vampire Thursday, July 16 at 8 p.m. in Theater Six at The Carolina Asheville and will be hosted by Xpress movie critics Ken Hanke and Justin Souther.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.