It’s hard to imagine a film more perfectly suited to appeal to a critic whose early love of film revolved heavily around vampire movies than writer/director Michael O’Shea’s debut feature, The Transfiguration. It’s a picture so steeped in self-referentialism that genre completists will want to see it at least twice. I spent most of my first viewing so distracted by all the deep-cut horror movie in-jokes that I needed to give it a second pass. This is a movie that ties a significant plot point to the fact that the Twilight series doesn’t understand vampire mythology and includes blink-and-you’ll-miss-it cameos from both Lloyd Kaufmann and Larry Fessenden — in short, the kind of movie that might have been made with me specifically in mind.

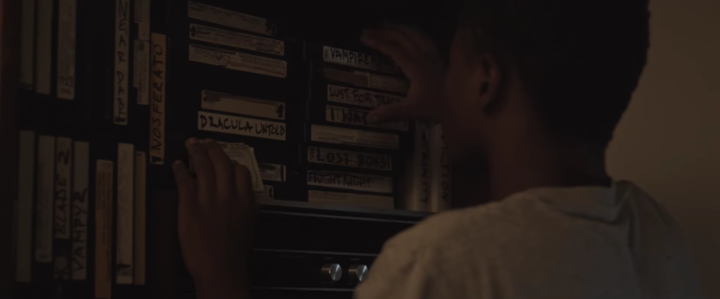

The Transfiguration is clearly a love letter to the vampire subgenre — overtly referencing earlier films rather than covertly borrowing from them, as is so often the case in the modern wave of throwback horror. These references come at the hands of our protagonist, Milo (Eric Ruffin), a vampire-obsessed 14-year-old black orphan living in the Brooklyn projects. Milo’s room is filled with VHS copies of classics ranging from Nosferatu to Kathryn Bigelow’s Near Dark, and when he finally connects with a slightly older girl who moves into his building, his conversational abilities begin and end with discussions of Let the Right One In and George Romero’s Martin. The Transfiguration is particularly indebted to these last two films, and yet it’s very much its own beast — focusing on the internal psychological dynamics of attachment to vampiric myth rather than on the creatures themselves.

It’s in this subtle shift from the normative approach to the genre that The Transfiguration finds its narrative and thematic footing, because there’s a slight catch when it comes to Milo’s newfound romance — his room is also filled with notebooks exhaustively detailing his methodology for hunting and feeding on human prey, as derived from his extensive study of horror movies. Milo may not be a vampire in the supernatural sense, but he is a serial killer with a thirst for blood, which understandably makes dating a little tricky. Milo’s fixation on verisimilitude in his vampire movies turns out to be largely practical, which goes a long way toward explaining his disdain for Twilight (beyond a rational qualitative assessment, that is).

The film is an externalization of Milo’s internal struggle, and as such, O’Shea distinguishes himself from filmmakers dealing with similar ideas through a minimalistic, almost detached approach to composition. Ruffin carries the film with a subtlety uncharacteristic of most actors his age, and O’Shea’s camera lingers on his impassive face with impressive restraint, allowing the audience to see the diabolical gears turning behind Milo’s dead eyes. Chloe Levine injects some much-needed warmth into the proceedings as love-interest Sophie, but even in their most touching moments of fleeting connection, the menacing background score never lets the audience believe that this could possibly end well. The third act hinges on a plot Milo has devised to free himself from his murderous impulses and Sophie from her abusive grandfather in one fell swoop, and to say that O’Shea’s script starts with a nihilistic streak a mile wide and only gets bleaker from there should provide some indication as to what’s in store.

Make no mistake, this film is dark — even by my standards, which is really saying something. If the film weren’t constantly name-dropping practically every noteworthy film in the blood-sucking cinematic canon, it would be challenging to even assign it to the horror genre. O’Shea uses his protagonist’s obsession with vampire movie lore to explore the fantasies of empowerment that identification with monsters can offer to those in positions of fundamental powerlessness and, in so doing, to try to understand the allure that committing violence can have for those who have endured significant trauma. It doesn’t necessarily make for a fun night at the movies, but The Transfiguration is an excellent example of what can happen when a filmmaker takes a genre typically inclined toward adolescent metaphors of sexuality and instead uses those tropes to penetrate the depths of a fractured psyche. It’s a challenging piece of work, but well worth consideration — and essential viewing for moviegoers with a soft spot for neck-biters. Not Rated.

Starts Friday at Grail Moviehouse.

Very surprised by the review. I thought it was horrible.