You Can’t Cheat an Honest Man was the first W.C. Fields movie I ever saw. That I saw it at all was partly the result of the fact that my mother hated Fields (that’s a plus when you’re 11 or 12), but mostly because I was in my hardcore horror movie phase and had adopted the belief that anything with a Universal logo on it had to be good. Things are simpler when you’re young, but that simplistic and just plain idiotic idea led me to be introduced to Deanna Durbin and the soap operas of John M. Stahl, too. Regardless, I was an immediate fan — a fan for life — and spent days quoting (or misquoting) lines from the movie to anyone who’d listen — no matter how unwillingly.

The movies have always loved the circus — and never so much as when they could parcel off a comic or a comedy team to its environs. The idea must have sounded better to studios and comedians than the reality. With the exception of Chaplin’s The Circus (1928), very few circus comedies rank among the best works of the performers at hand (just look at 1939’s Marx Brothers picture At the Circus). W.C. Fields’ You Can’t Cheat an Honest Man is a fairly happy offshoot — for the simple reason that it rarely is a circus picture in any normal sense. It wastes no time depicting supposedly entertaining circus acts. It’s nothing more than a setting for Fields to wander through and express the utmost contempt for the rubes that make up the audience for his fairly low-rent circus. When he’s not cheating customers at the ticket window (“No mistakes rectified after leaving the box office!”), hoodwinking the union, he’s shamelessly promoting acts like palming off two men of normal height as “the smallest giant in the world” and “the tallest midget in the world,” assuring the gullible throng, “They baffle science.”

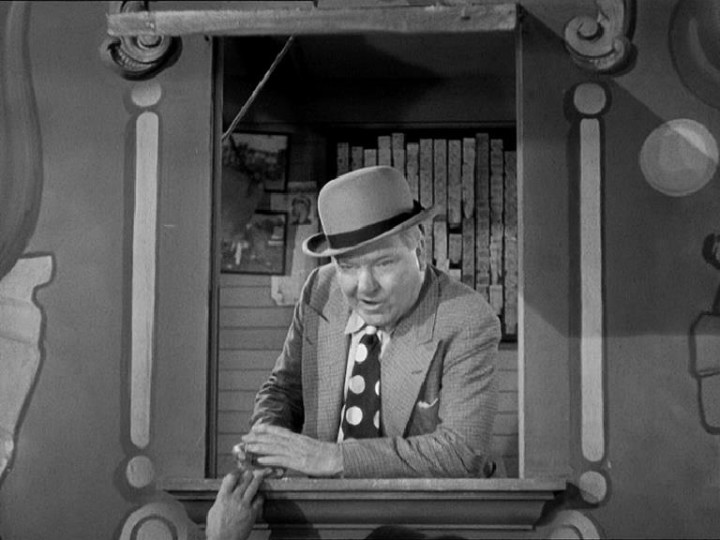

Fields also ineptly and improbably doubles for missing performers like Buffalo Bella, “the only bearded lady sharp-shooter in the world.” At one point, he even fills in for the supposedly ailing Edgar Bergen and — with the aid of a fake mustache and oversized false teeth — gives us quite possibly the worst act in the history of ventriloquism. And that brings us to the film’s real ventriloquist act — Edgar Bergen and Charlie McCarthy (with the help of additional dummy Mortimer Snerd). Immensely popular at the time, a little of them goes a long way today. It probably doesn’t help that Bergen isn’t a very good ventriloquist, but at least he — and the film — has the good humor to poke fun at the fact that you can very clearly see Bergen’s lips move when he works. But remember, it was the presence of Bergen and his wooden friends that made the film possible in the first place. If it hadn’t been for Fields’ radio feud with Charlie, it’s unlikely that Universal would have made the film in the first place.

What’s surprising is how much of the film is given over to Fields just being Fields. In fact, the scenes most people remember today are the ones where Fields destroys his daughter’s engagement/wedding party. Though probably based on a similar scene in Fields’ first sound feature, Her Majesty Love (1931), this is much more elaborate and filled with Fieldsian digressions. Not only do we get the delight of the Great Man tormenting his herpetophobic hostess by insisting on relating wild tales involving his friendships with snakes, but the whole movie comes to a screeching halt so that Fields and Ivan Lebedeff can engage in a ping pong game to for the occasionally uncomfortable benefit of his old screen nemesis Jan Duggan. While this sort of thing would be disastrous in most movies, it works perfectly here.

For as much fun as You Can’t Cheat an Honest Man is for the viewer, it was not an especially happy production. For whatever reason Fields and director George Marshall didn’t hit it off. Chances are good that this was Fields’ fault. Marshall was a comedy specialist who managed to work harmoniously with Laurel and Hardy, Bob Hope, and even Martin and Lewis. Fields, on the other hand, was notoriously cantankerous and easy to offend. The tension became so bad that Fields’ old director pal Edward F. Cline was brought in to direct his scenes, leaving Marshall with the plot and the Bergen-McCarthy material. You can’t tell that the film had two directors. How could you when the film is such a gloriously — and deliberately — preposterous mess in the first place?

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.