By Jack Igelman, Carolina Public Press

Editor’s note: This story is co-published by Carolina Public Press and Mountain Xpress.

Some Western North Carolina community water systems are so old that the water in your glass may have traveled there through wooden pipes buried a century or more ago.

Is this just a folk tale? Hendersonville Water and Sewer Utilities Director Lee Smith hasn’t seen a wooden section in his 10+plus years of service — but he won’t rule it out.

“It is possible. Our earliest pipes date back to the 1880s,” Smith said of the second-largest water system in North Carolina’s 18 westernmost counties.

What isn’t a folk tale is that it’s no simple — or inexpensive — task to keep the 580-mile water system serving roughly 62,000 people afloat, Smith said.

As is the case in many government-owned water systems, Hendersonville water consumers pay service charges that offset a significant portion of the utility’s expenses. For the 2015-16 fiscal year, the city anticipated that water-and-sewer services expenditures would reach $24.7 million. Of that, $1.9 million was dedicated to water maintenance and construction.

“We have to prioritize,” Smith said. “We have a pretty significant inventory of pipeline that needs to be replaced. But we’re no different than any other system our age.”

Indeed, they aren’t alone. Figuring out ways to preserve, repair and enhance decades-old — or even century-old — water systems provides a flood of challenges for cities, towns and communities across North Carolina’s mountains.

And, experts say, ownership structures of those water systems may influence infrastructure upgrades, service quality and the ultimate price water users – that’s you, the people with glasses of water in your hands – pay.

Who owns your water now — or in the future?

Katie Hicks, the assistant director of Clean Water for North Carolina, a nonprofit water advocacy organization with an office in Asheville, is at least one person who pays close attention to who owns and operates drinking water systems in the mountains.

“We are water rich in Western North Carolina, but there will be many more users in the future, so it’s important to think about who has the right to use the region’s water,” Hicks said. “Some models of ownership and management of water are more transparent and more responsive to the needs of residents.”

She cautioned that more industry and development in the region will add stress on the water supply, and that climate uncertainty — such as drought — can also make the rights to water and decisions about how it’s allocated a slippery topic.

Right now, roughly 2.3 million North Carolinians rely on private wells. But the majority of the state’s residents tap into a public water system.

According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, a “public” water system provides service to 15 or more households or 25 or more individuals, regardless of who owns and operates the system. Homeowner groups, municipalities, counties or private utility companies, to name a few, may own these water systems and are, therefore, charged with making sure supplies are safe and consistent.

According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, a “public” water system provides service to 15 or more households or 25 or more individuals, regardless of who owns and operates the system. Homeowner groups, municipalities, counties or private utility companies, to name a few, may own these water systems and are, therefore, charged with making sure supplies are safe and consistent.

Yet, exactly who will manage the challenge of delivering this water isn’t certain. Across the nation, investor-owned utilities are playing a larger role in managing large public systems. While that’s yet to take hold in North Carolina, the future of who owns and operates public drinking water systems in the mountains is murky.

A 2013 North Carolina General Assembly law transferred the Asheville-owned water system — the largest system in WNC — to a new regional water and sewer authority. The city successfully challenged the law in 2014, however, the state has appealed. I. Faison Hicks, a special deputy attorney general arguing for the state, said during court arguments in June that since the water system and the city itself are charted by the state, the water system doesn’t belong just to Asheville and its citizens.

“Municipal public water systems belong to the state,” he said.

If the state’s appeal is successful, Asheville Mayor Esther Manheimer told Carolina Public Press the new law will have sweeping consequences for cities and towns across North Carolina.

“I think there’s a concern that, if the state prevails, it means that cities don’t own their proprietary assets,” she said. That, she said, would impact the financing of projects and municipal decisions about upgrading aging systems.

While the impact of the court’s ruling could be most acute in Asheville, it may also challenge the status quo of water system ownership across the state.

Among those North Carolinians who tap into community water systems, 87 percent currently get water from a government-owned community water system. But systems with large debt or facing costly repairs may have incentive to privatize, merge with other utilities or transfer ownership to other public operators.

The Polk County Board of Commissioners is facing such issues, and is currently considering the long-term transfer the control of its water system to a district in South Carolina in exchange for improvements and maintenance.

Opponents of the plan have said that leaders are rushing to give away one of Polk’s most precious resources. However, a majority of county commission members have said the water system’s expenses are disproportionately large relative to the number of customers it serves, and they are continuing efforts to negotiate a management contract.

A distress to the system, or saving a system in distress?

Could other communities follow suit?

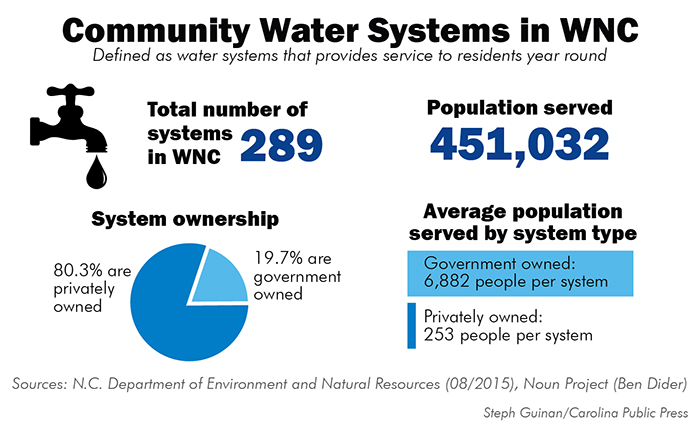

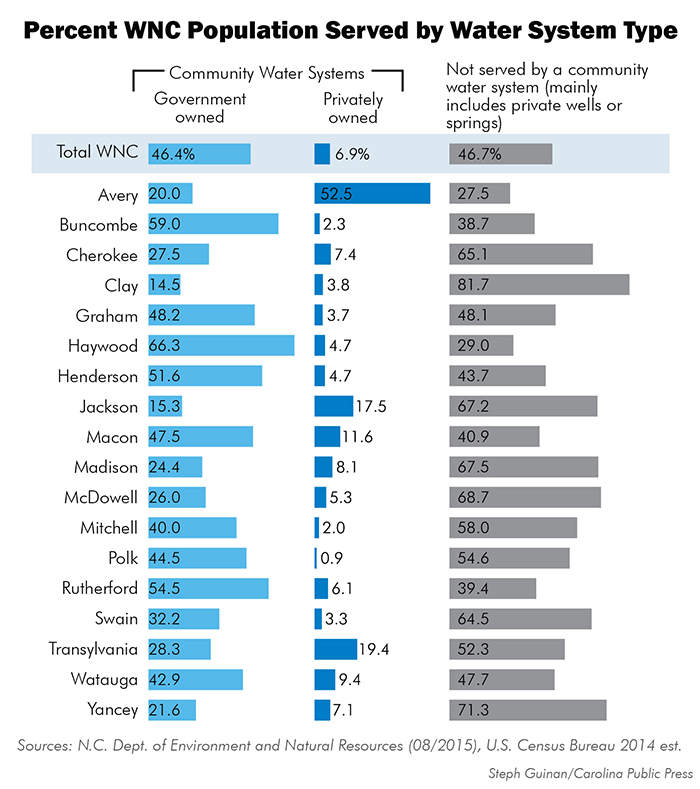

According to the Public Water Supply Section of the N.C. Division of Water Resources, 289 community water systems are active in the 18 westernmost counties of the state. A community water system is one that provides service to residents year-round and can be operated by local governments or can be privately owned.

Among the 451,000 residents who depend on community water systems in WNC, 87 percent receive their tap water from government-owned utilities.

But in rural and suburban areas, small water systems serving fewer than 500 customers are common, and many are already operated by private companies. While most water systems operated by private companies are small, among the total number of community water systems in WNC, more than 80 percent are operated by private owners.

But in rural and suburban areas, small water systems serving fewer than 500 customers are common, and many are already operated by private companies. While most water systems operated by private companies are small, among the total number of community water systems in WNC, more than 80 percent are operated by private owners.

Tom Roberts, president and chief operating officer of Aqua North Carolina, a subsidiary of Aqua America, predicts that ownership of larger municipal water systems by investor-owned utilities will be more likely in the future. Aqua America is a publicly traded water and wastewater utility with operations in eight states.

“I think the water industry continues to change nationally and within the state,” Roberts said. “At some point, they [government-owned utilities] are going to have to look at alternatives.”

Statewide, Aqua North Carolina operates 750 water systems in primarily small rural and suburban areas in the Piedmont and farther east. In all, the company serves 77,000 connections, or roughly 250,000 North Carolina residents. In WNC, the company operates 14 community water systems, serving less than 1 percent of all water users.

According to Hicks, as development in the 1960s, ‘70s and ‘80s moved beyond city and town limits and the reach of municipal water systems, communities began to rely on wells for water. Some of those systems across the region have been purchased by investor-owned utilities, such as Aqua North Carolina, and another major corporate player, Utilities Inc.

Utilities Inc. owns water systems in 15 states. In WNC, it operates Carolina Water Services Inc. and other subsidiaries, which own 24 community systems that serve more than 22,500 customers — or 5 percent of all community water users in the 18 westernmost counties.

And while Hicks and Roberts agree that aging water systems will be an incentive for municipalities to privatize, Hicks is uneasy about the trend.

“Government officials have a level of accountability to voters, which gives them an incentive to provide reasonable service and be transparent,” Hicks said. “The U.S. has a long history of public entities like local government doing a really good job providing water.”

While both corporate- and government-owned systems are subject to the same environmental regulations, their rates set differently. Investor-owned utility rates are regulated by the N.C. Utilities Commission. Government-owned utility rates are set by the utility’s governing body. For example, the Hendersonville utility’s rates are set by the five-member City Council.

On average, according to Hick’s organization, Clean Water for North Carolina, investor-owned utilities charge higher rates, which may place a greater burden on lower income households. The organization is also concerned that those utilities’ customers have a limited ability to hold private companies accountable for service and quality issues. What’s more, it worries that the state’s regulatory body lacks the necessary resources to oversee such a large number of systems and has allowed rates to rise without adequate justification.

Roberts, with Aqua North Carolina, disagreed.

“I would argue that the public has a larger opportunity to hold companies like mine accountable,” he said. “When it comes to ratemaking, decision-makers [elected officials] can change rates pretty much as they see fit. At the end of the day, [elected officials responsible for rate-change approval] don’t have a set of rules that they have to follow. We work hard to keep our rates reasonable, but we also understand we have to invest in our systems to reflect the level of service our customers expect in our systems.”

Aqua North Carolina’s strategy of expansion often involves working with a developer at the ground level or buying existing privately owned water systems; it seldom contracts to build new systems. Roberts said that investor-owned utilities are often the only option for systems in distress.

“We bring an alternative to the table for systems that may [face] a big investment necessary to meet regulatory compliance or they want take their asset and sell it to a private utility and take those funds and go do something that is more important to them,” he said.

Aqua North Carolina may have a small footprint in WNC, but he said that it could grow. Among the advantages of a corporate-owned utility, he said, is the capacity to spread risk over a large, statewide customer base and access financing that may be unavailable to public entities.

While the privatization of large municipal water utilities has yet to take hold in North Carolina, Roberts said the tide may shift as public operators struggle to keep up with an aging infrastructure with limited resources.

But the city of Hendersonville is well positioned to manage and improve its system into the future, according to its Water and Sewer Utilities director.

“We really feel that it’s in our customers’ best interest to be the ones that lead this utility into the future. Our customers have more input [into] the way that things are now,” Smith said. “We would certainly like to see it [remain] the way it is. As Asheville has learned, that’s not always our choice.”

Jack Igelman is the lead environmental contributing reporter at Carolina Public Press. Contact him at jack@igelman.com.

“Municipal public water systems belong to the state,” he said.

This is a radical suggestion that has been rejected by the NC Superior Court. Other municipalities are waking up to how much damage the State can do, if this notion is allowed to stand. Wilson, NC knows it – their water system and reservoir are being lusted after by nearby Raleigh, who is making noise like they want to simply take it, despite the fact that Wilson taxpayers paid for it. So Wilson filed an Amicus brief in the Asheville lawsuit appeal. The decision is weeks overdue…

Katie Hicks and I penned an op-ed in 2012 about the prospect of privatization being an unstated motive in the attempted takeover of Asheville’s water, especially given the apparent predilection of the legislators behind it.

http://mountainx.com/opinion/010412private-business/

The day after it came out, Rep. Moffitt called me at home, upset that I had implied he favored privatizing Asheville’s water system. He denied that this was his motivation, and in public, he has steadfastly rejected that it is his desired end goal. However, as we debated the merits and drawbacks of privatization generally, he let slip comments like: “Barry, what’s your problem with profit?” I think he firmly believes that if some private company wants to see if they can generate a profit operating a public enterprise, the overarching imperative is for government to get out of the way and let them do it. The long history of failed water privatization in the US, and the valid concerns of residents, ratepayers, and elected officials are of lesser importance. This is bedrock philosophy at the American Legislative Exchange Council, BTW, where Tim was a member of the Board of Directors.

Those of us who believe that public water systems should stay in public hands have to stay vigilant, because the private water industry and their sympathetic public officials won’t sleep until they get their hands on our water. And then what was a shared public resource will turn into a commodity, and a source of private profit, at our expense.

http://saveourwaterwnc.com/