“The plan needs to be sustainability. After the international aid is gone, there must be programs the people can continue themselves. Until then, there won’t be any real change.” — Rebel Lyonn, Haitian activist/reggae star

“I know a guy who wants to give Haiti a well,” Todd Kaderabek of Mission Manna told me over lunch last February. The Asheville-based group has been bringing volunteer medics to that island nation for nine years.

This was big news for me. After graduating from UNCA in 2010, I traveled to Haiti in the wake of that January’s devastating earthquake; two years later, the country’s struggle — and resilience — persist. I now live just outside Port-au-Prince coordinating The Compassion Project, a community-organizing and school-support program I founded.

But it was also big news for the Haitian activists who’ve inspired me and helped guide my work.

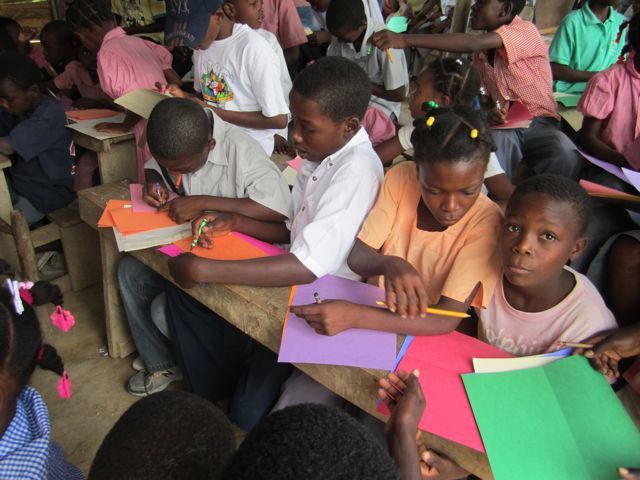

The Compassion School in Savenette Cabrale, a small rural community in Haiti’s central plateau, serves 200 children from the lowest-income population. The eight teachers organized the K-6 school themselves (the area’s only tuition-free school), working without pay for 10 years.

“The people are strong in their minds and spirits — they are still hopeful, optimistic,” says my friend Rebel Lyonn, a well-known Haitian reggae artist and social activist who played a benefit concert (live via Skype) at White Horse Black Mountain just after the 2010 quake. “But although there are smiles on their faces, inside of them there are scars.”

That’s no news to Asheville resident Albert Seale, the 63-year-old retired military anesthesiologist who aims to bring clean water to Haiti. Six weeks after the cataclysmic earthquake, Seale traveled there with other Asheville and WNC health professionals for 10 days of volunteer work.

“I was less impressed by the devastation, massive though it was, than by the positive response of the ever-hopeful, hard-working Haitians trying to mend their broken lives,” Seale recalls. “The smiles of the men, women and children of Haiti inspired me to do more to help them when I returned to the United States.”

Lyonn, too, has seen both his countrymen’s tenacity and courage and the work of international aid organizations up close, having spent many months helping create a “child-safe space” inside one of Port-au-Prince’s biggest tent camps. “I felt I had to contribute in some way — I could not just sit there and watch foreigners trying to help,” he explains.

In adapting to other cultures, says Lyonn, some Haitians have lost sight of traditions that fostered self-reliance. And well-meaning outsiders’ ignorance of the culture and failure to focus on sustainable outcomes often wastes time and money.

“Haiti has different customs, it’s a different state of mind, so there are different ways to bring solutions,” Lyon asserts. “If you don’t know those ways, even with all the resources, you will not affect the people directly.”

“In our culture, we have something we call ‘konbit,’ where people ‘put hands and hands together,’” he explains. Communities help each other, rather than just depending on outsiders for aid.

“There has to be a way to get the people back into the konbit state of mind: Each one teach one. This is what Haiti must rediscover for real change to come.”

Willing hands and minds

That’s the idea behind The Compassion Project: empowering Haitians to create the society they envision by supporting existing community structures.

We raise funds for projects implemented in partnership with a Haitian group, Konbit Humanitaire Nationaux. And our twice-yearly trips let Americans experience Haiti firsthand.

Last year, we raised $25,000 for teacher trainings, salaries, uniforms, textbooks and construction materials. But then I learned that the school’s closest water source was unreliable and we needed to drill a well. Where would that money come from?

Back in the U.S., Albert Seale heard about the severe cholera outbreak caused by a lack of basic sanitation infrastructure — and realized how he could help bring sustainable change to Haiti.

“Clean water is the primary weapon to fight many of the gastrointestinal diseases and infections which kill thousands in Haiti,” notes Seale. “I felt powerless to do much alone, but I knew that with other willing hands and minds, we could make a difference. So I asked my Lutheran church, St. Mark’s of Asheville, if we could seek out and help a community in Haiti that needed a well drilled.”

They searched for months, till Kaderabek referred them to The Compassion Project. With donations from congregation members, Thrivent Financial and St. Mark’s Christian Action Committee, $4,800 was raised, and the church has engaged Healing Hands International. The drilling should begin this month.

Amid the continuing struggle, Asheville residents are helping create a cross-cultural konbit. By taking time to truly understand Haiti and empower its people, we forge a global community of people who learn from and help one another.

Former Asheville resident Lorin Mallorie lives in Port-au-Prince, Haiti.

To learn more about The Compassion Project and how to get involved, visit http://savenettecabrale.org.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.