Let me say from the onset that this particular column isn’t aimed at moviegoers who like to argue that certain people (like myself) “overthink” movies. It’s not aimed at passive viewers. No, it’s aimed at people who view the process of movie watching as a kind of inner dialogue between the viewer and the filmmaker—at those who actually enjoy the idea of interpreting what a movie is all about. Perhaps it would be safer to say what a movie may be about.

There are theories on the topic of how to “read” a movie. There is even at least one book that purports to teach the reader exactly how to do this. I confess I’m a little skeptical of the existence of a firm set of guidelines on how a movie should be read. Oh, sure, there are ways of doing this in a purely technical sense. You can study the composition of the shots, the positioning of the characters in the frame, the manner in which the film is edited, and so on. This will afford you some insight into what the filmmaker was after. If, for example, a character is shot from an extremely low angle, the shot gives that character a certain power. It can—to use a fairly famous example—be used to convey snobbery, as in the shots looking up at the butlers as they watch Maurice Chevalier leave a chateau in “disgrace” in Rouben Mamoulian’s Love Me Tonight (1932).

Textbook examples of other specific approaches abound. The use of subjective camera—or point-of-view—can convey many things. The overall concept is this type of shot—where the camera becomes the eyes of the character and by extension the eyes of the viewer—draws the viewer into the character. There are a great many examples of this approach throughout the history of movies. The most famous—or most notorious, since it comes across as a largely failed experiment—is probably Robert Montgomery’s film of Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe novel, The Lady in the Lake (1946). In this peculiar film, the entire story is told through the main character’s eyes. It’s as fascinating and as awkward as that sounds. Simpler uses tend to work better—the single shot of Tommy (Roger Daltrey) looking up at his Cousin Kevin (Paul Nicholas) torturing him in Ken Russell’s Tommy (1975). For a fleeting moment we actually do seem to become the character—and this despite the fact that the character is psychosomatically blind. (Dramatic correctness trumps realism every time when you’re working in a stylized manner.)

This sort of thing is very useful in taking a film apart to see why it works or doesn’t work, but it doesn’t actually get to the heart of the thing. These are merely tools to illustrate the why of it all. The actual sense of the work is a wholly subjective process of how the viewer personally connects to the film. You could argue—and in some cases with validity—that the film has failed if it doesn’t make that connection. But in many cases, what you’re saying is that the film has failed for you. (Yes, this can be taken to ridiculous extremes, but that’s a separate issue.)

A reading of a film is an interpretation of it. It is simply what the film means to the person interpreting it. Its value beyond that lies in the possibility that such a reading has the power to make us look at a film—even a film we think we know—in a different light, from a different perspective. The problem with this lies in an all too common assumption that a reading should be somehow definitive. Nonsense. Balder and dash. Poppy and cock. Flap and doodle. A reading is just a reading. It may prove interesting. It may make us see a familiar work anew. But definitive? No. And that’s a good thing. Look at it this way—a work of art capable being interpreted one way and one way only is almost certainly not worth interpreting at all.

More than this, however, our own readings of films are apt to change over the years—and if they don’t, there’s something wrong. If my reading of James Whale’s Bride of Frankenstein (1935) was the same as it was when I first saw it around the age of 10, chances are I wouldn’t still be watching it 44 years later. At least, I would hope not. That’s an extreme example, but really we should constantly be re-evaluating—or at the very least be open to the possibility. Movies change with the years because we change.

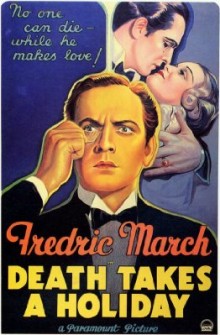

This was brought home just this past week when an old friend of mine expressed a desire to see Mitchell Leisen’s Death Takes a Holiday (1934), a film I’d introduced her to when we were in high school. The film has shown up on TCM on occasion and was briefly available as an “extra” on the “Ultimate Edition” of Martin Brest’s 1999 remake Meet Joe Black (which is the only reason I have a copy of Meet Joe Black). Since I could, I offered to make her a copy of the film, which, of course, required watching it—or at least having it on. I should have realized that this isn’t a film I could just have on, so I actually ended up watching the whole thing.

For those not familiar with the film, Death Takes a Holiday is a romantic fantasy that concerns Death (Fredric March) deciding to assume the form of a late nobleman, Prince Sirki, in order to live among mortals undetected in order, he says, to understand why men fear him and cling to life. His motives are actually a bit deeper than that statement. He wants to experience life as much as an antidote to his eternal loneliness as from any desire to understand it. Late in the film he says that he came to this world to find “a game worth playing.” The “game” he finds is, of course, love, which he realizes in the form of a strangely ethereal young woman named Grazia (Evelyn Venable).

It’s a richly rewarding film on a number of levels, though one that may require a little—let’s call it, suspension of modernity. Personifying Death is a tricky business that works better as a period piece, which, by now, 1934 has become. It also carries with it a certain level of pretension, which may, in the case of the film, be less inherent in the original material (this was first an Italian play by Alberto Cassella that was adapted into an English version by Walter Ferris) than in the participation of Maxwell Anderson as co-author of the screenplay. Anderson’s penchant for hifalutin dialogue is likely responsible for a few of the movie’s more purple outbursts—most of which are limited to the early scenes with Death, where the character is prone to theatrical outbursts about “taking on the world, the flesh and the devil.” These are things modern viewers may need to adjust themselves to. It’s certainly worth it for the film’s rich beauty and cumulative effect.

It might also be worth noting that Leisen’s film wasn’t exactly given a huge budget. To the untrained eye, it looks pretty lavish, but anyone familiar with Paramount’s early 30s output will notice more than a couple recycled sets and decorations. (One of the advantages of the studio system is that there was a vast array of sets and props at hand.) Death Takes a Holiday was only Leisen’s second full-blown directorial effort, but it’s an amazingly assured work that takes full advantage of everything it has to work with. Plus, Leisen’s earlier work as an art director afforded him the ability to help camouflage the redressed sets or put a fresh spin on them.

I’ve known the film most of my life. I’ve loved it the entire time. For that matter, it wasn’t that long ago that I screened it for another friend and still found it a very moving fantasy with touches of mordant humor and a surprisingly resonant climax. The scenes on the moonlit terrace where Prince Sirki and Grazia dance to Jean Sibelius’ “Valse Triste” were still expressive of idealized romance that held their power and beauty. (One wonders, however, what Sibelius must have made of the dance band arrangement of the piece over the ending credits.) The simple effect where Sirki reveals his true self (“I will you to know who I am”) to a woman (Katharine Alexander) who has expressed fearless love for him was still a superb piece of filmmaking. But I don’t know that I “got” anything new from that screening, except for being a little surprised how obvious it is that Sirki and Grazia consummate their love in an offscreen passage of time.

This time—for whatever reason (and I could probably decipher that, but it’s immaterial)—something new did happen. It suddenly struck me that the film could be read as a work brimming with gay subtext, which isn’t even far-fetched since Leisen was gay. (Yes, there was a Mrs. Leisen, but let’s not go into that.) It’s not a given—especially during the era in which the film was made—that that aspect of the filmmaker would come through onscreen, but it does increase the chances.

In the case of Death Takes a Holiday several factors come into play to support such a reading. There’s the character of Grazia herself. Even in the film’s clever opening credits where the players are introduced with their character names superimposed, everyone is shown grouped together at an autumn carnival—everyone except Grazia (and Death, who isn’t in the scenes and receives no such treatment), whom we meet via a dissolve to her apart from the others, by herself in a church. It quickly transpires that there is a kind of unofficial engagement between her and Corrado (Kent Taylor), a perfectly nice and likable young man, who is the son of their hosts Duke Lambert (Sir Guy Standing) and his wife, Stephanie (Helen Westley).

Grazia likes Corrado. She even loves him, but when pressed on the point of marriage by Corrado, his parents and her mother (Kathleen Howard), she balks. “You know I love you all, and I want to please you, but I…” she tells them and walks away leaving the statement hanging, before turning at the door to the garden and saying, “Don’t you see? I’m not ready.” She further tells Corrado, “There’s a kind of happiness I want to find first, if I can.” Beyond that she talks about a “something” that she “must understand” before she can settle down with Corrado to a conventional normal life. The fact is that there’s nothing in the world wrong with Corrado. He’s handsome, caring, personable and likable, but something holds her in check, but even late in the film she tells Corrado, “I love you in some way I can’t quite make clear. If I didn’t feel so far away, I’d be in your arms now, crying and holding you close to me.” It’s not for want of caring for him, but something else—something beyond what she would even like to be true—that stands between them.

Of course, what she finds is love in the form of Prince Sirki—a love that the others can’t understand and find frightening, especially when they learn the truth of just who Sirki really is. Even Grazia is not on perfectly solid ground in the matter. She tries to reason with her friends, family and would-be husband. “Why are you all so strange? Why are you suffering so? I’ve found my love. There ought to be lights and music,” she argues, but when Corrado asks her to stay with him rather than go with Sirki, there’s a sadness to her response, “I can’t, Corrado, but I shall always love you.” The fact is that she has finally learned that “something” she had to understand and is now the person she secretly knew she always was.

Am I claiming this is the definitive reading of Death Takes a Holiday? No in the least. I can even see an aspect of the reasoning that contains—well, not so much a flaw, but an unpleasant undercurrent that is only swept aside by the romanticism of the overall film. What I am saying is that this is a possible way of looking at the film. The reader is at leisure to examine it, accept it or reject it. My purpose is the same in either case—to get you to look at the movie in a way that you perhaps haven’t considered. Even if you conclude that I’m filled with the juice of the prune, you’ll have looked at the movie as something alive and not merely some dusty old classic. And that’s really the point—and it should be the point behind any reading of a film.

Being a color theorist, I was interested to see the phrase “purple outbursts.” Is it regional, or just antiquated? A google search failed to turn up any etymology. In fact, there were only two references on all of google where those two words were stuck together with similar intent; one was in a book discussing Truman, and the other was in a Hildegard Hoeller book on “Edith Wharton’s Dialogue with Realism and Sentimental Fiction,” which is serendipitously apt to your article:

http://books.google.com/books?id=eVHsR6nwEIIC&pg=PA103&lpg=PA103&dq;=“purple+outbursts”&source=bl&ots=idpyCJ7FFD&sig=2Rl960ryaxXIyZASR6m3Uw9EUAQ&hl=en&ei=VdTxSarjCZeltgeg252-Dw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2#PPP1,M1

Being a color theorist, I was interested to see the phrase “purple outbursts.” Is it regional, or just antiquated? A google search failed to turn up any etymology.

That’s odd because if you type in the term “purple prose,” you should get several suggestions. It’s a fairly common literary term for writing that is overly ornate or flamboyant, etc. Perhaps you need the specific addition of the word “prose,” but I’m used to seeing purple used to describe writing without the second word.

Ahh, thanks, “purple prose” solves it for me. I searched for “purple outbursts” and got almost no results, but “purple prose” yielded many results including etymology.

a work of art capable being interpreted one way and one way only is almost certainly not worth interpreting at all.

What a fantastic quote! This is the sort of thing that has oftentimes been sitting on the tip of my tongue, and yet I simply failed to put it into these words. This says so much with such a small amount of verbiage.

This is why it seems pointlessly juvenile to become so angry and frustrated over someone else’s ‘interpretation’. What I don’t fully understand is why people take ones subjective opinion of a movie so seriously (or personally, to be more to the point), but with other forms of art (like a painting) it often can be far more acceptable to see things completely different. Maybe these so-called ‘passionate’ viewers just don’t see movies as belonging in the same art category as these other art mediums. But if one doesn’t look at (or for) these artistic subtleties within a good movie, then one is missing out on a good deal of the movie.

What a fantastic quote!

Thank you.

This is the sort of thing that has oftentimes been sitting on the tip of my tongue, and yet I simply failed to put it into these words. This says so much with such a small amount of verbiage.

I am so rarely accused of using “a small amount of verbiage.” Just ask anyone who’s ever edited me.

This is why it seems pointlessly juvenile to become so angry and frustrated over someone else’s ‘interpretation’.

Juvenile is perhaps the best word for it. I can recall getting very worked up over such things when I was 14. I long since got over the need to get bent out of shape over any interpretation, though, sure, I find some rather silly. But even silly can be fascinating on occasion.

Rather interestingly, the idea of subtext is upsetting to some people — and the idea of gay subtext even more so. This is especially true when dealing with “classic” movies. About 11 years ago I wrote a very long article on Bride of Frankenstein for Scarlet Street magazine — and made a case for the film being an expression of James Whale’s coming to terms with his homosexuality. (In so doing, I touched on gay elements in his other three horror pictures — Frankenstein, The Old Dark House and The Invisible Man.) Well, you’d have thought I’d committed the ultimate heresy in certain quarters. Not only was the reading branded “ridiculous” and “absurd,” it seems I had also “forever tainted” these films that those who objected to the article had (and I think this is key) “loved since childhood.” Now, maybe I’m missing something, but I have trouble seeing just how the article could be nonsense and could forever taint these movies at the same time. One or the other, sure, but both?

I’m not sure if I should have read this column before watching “Death Takes a Holiday” because the reading you discuss here, is going through my brain while I’m watching it. It’s not a bad thing; I just find it complicated to think of something of my own without hearing the echo of your words.

So, pushing those thoughts back,what I got from it on my first viewing was probably what everyone else would, ‘death is not to be feared,’ and ‘true love surpasses death.’ What I also got from it was ‘the bad guy is just misunderstood and has needs and wants like all of us.’ Then there is also the theme of ‘letting go.’

Excellent film, I’m really glad I saw it. Death, himself, is just so likable, and he reminded me of Bela Lugosi (the way he sounds when he talks about wine). Like, what if Dracula could go out in the sun and be normal for a few days (hmmmm, I kinda like that concept…). This movie is also hilarious, just a great movie experience overall. “Death Takes a Holiday” has the right amount of everything to prove it’s classic status. I’m curious to see “Meet Joe Black” now.

Death, himself, is just so likable, and he reminded me of Bela Lugosi

Considering it was made a scant three years after Dracula that’s likely not coincidental.

“Death Takes a Holiday” has the right amount of everything to prove it’s classic status. I’m curious to see “Meet Joe Black” now.

On the first part of that, I completely agree. As to the second part of that statement, let’s just say you’re on your own.