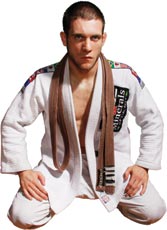

Preston Marks likes to roll. That's his word for getting down on the mats and sparring in jujitsu, an ancient Japanese martial art. But despite the 14-stitch gash on his forehead (from an accidental head butt during practice), don't imagine he's some hulk: Marks is all of 5 foot 6 and about 150 pounds. Polite, prompt and perfectly dedicated, the stocky 26-year-old says there are a lot of myths and misconceptions about martial arts, starting with this one: "We're not a bunch of meatheads trying to beat each other up every day."

Nor is a jujitsu match some choreographed creation like the fight sequences in a Jean-Claude Van Damme or Jackie Chan movie. There are no secret moves, no "death touches" and no single, fancy move that will work on any assailant.

"Doesn't exist," Marks says flatly. "I don't know — talk your way out of it? Run?" he adds, laughing.

Jujitsu does have practical self-defense applications, he continues, but for the most part it's a gentle martial art that emphasizes throws, grappling, joint locks, pins, chokeholds and the like. It's similar to Western-style wrestling though far more immersed in the philosophy of self-improvement and the search for peace, Marks explains. "The word 'ju' comes from 'wa,' which means accord. It's the art of accord, or doing things accordingly. That doesn't mean the application is gentle, but the philosophy is gentle — not using your energy; using theirs. Jujitsu is not fighting. It's just that: not fighting, not resisting."

In competition, Marks has applied both philosophy and practice successfully enough to qualify for the World Jiu-Jitsu Championship in Long Beach, Calif., June 4-7. He didn't make it into the medal rounds, but just getting to compete represents another big step toward fulfilling a dream he's had since kindergarten: trying to become a world martial arts champion.

Much as he'd like to win, however, Marks ultimately views such endeavors as simply further stages in his own continuing evolution. He tells of watching "some 20-year-old who's got all the stamina in the world just going totally nuts and exhausting himself trying to pin a 70-year-old expert — who doesn't even break a sweat before getting the submission hold." Says Marks, "True perfection is making things look effortless."

Marks took a break from preparing for the World Jujitsu Championship at his studio, Asheville Brazilian Jiu-jitsu, to talk with Xpress recently about the martial art, his personal outlook and the broader philosophical implications.

Mountain Xpress: How would you describe competitive jujitsu?

Preston Marks: It's much like judo, [with] takedowns awarded points, like in wrestling. But then after that it's a position game, [seeking] maximum leverage with minimum effort. The whole idea behind it [is], as you advance up the body, you increase leverage. So if you can get around their feet, that's called passing their guard, so there are points for that and for sweeps. And then you advance up the body, and you're awarded points for different positions (side control, knee on belly) and mounts, front and back. … The objective is [getting] the submission, the joint lock [or] the chokehold.

How did you get into it?

I actually got into martial arts when I was 4 [years old], with my sister. By the time I was 8 or 9, we got sponsored on a national karate team. We were going to tournaments around the nation and all over the world — 14 to 16 a year. So we were always bouncing around and doing the karate thing in the early '90s. [That's] about when [a teammate] introduced me to jujitsu; then I later started training out of Cesar Gracie's [academy] in California.

So you do Brazilian jujitsu?

Yes. The Gracie family learned it from Mitsuyo Maeda, who came to Brazil [in the early 20th century and was instrumental in developing judo and jujitsu there]. But the jujitsu I practice and preach now is not the same as I learned it even 10 years ago, because guys are constantly reinventing [it]. If you're tall and lanky, there are techniques for you. If you're short and powerful and explosive, there [are] techniques for you. So [it's] this constant cycle of people figuring out new techniques, new setups, and you evolve new defenses. The sport evolves.

How is it different from mixed martial arts?

There are no strikes. You have to wear the uniform, which is the gi. It's less violent, more slow and technical, because you end up on the ground where [spectators] can't notice what's going on. Some people refer to [jujitsu] as "chess between bodies." I do one move, you have three escapes; off each one of those escapes, I've got three moves; each one of those has three more; and the tree just gets so big. And it's chess: You get the guy a step or two behind, and it steamrolls. That's hard to describe to someone when they're just seeing it as grrr! two people [grappling]. They're [asking], "What's the 'secret' move?"

What's your secret?

How about just complete dedication? That's a beautiful thing. I've read that it takes 14,000 times to get muscle memory. That's a lot of practice — and that's one side. So I [can't] come in and do 10 arm bars [a joint control] on the left side and 10 on the right and say, "I've got it." Well, I'll do that one [move] for five years, and then I might have it.

What's your ultimate goal?

There's no end goal, [except] to keep training. It's a full circle. A lot of people start off learning the more traditional jujitsu and get into the sport aspects, then come all the way around and realize the traditional stuff was the most important. But in that evolution, I've heard people say that after becoming a black belt, it's all about becoming a white belt again. [The belt] disintegrates, and all the black falls off and becomes white. That's really what it comes back to.

The path is the most important part, and to be able to do this with your friends, to build relationships, to challenge yourself physically, mentally and progress, that's all we really can ask in anything we do. And in my life, I've found the best avenue for that: jujitsu. I'm not always going to be the youngest, strongest buck. There's always going to be some guy [better], but that's not what it's all about. It's not about being the best, even in the world.

There’s no mention of location (unless I’m blind :) ) – would you mind letting me know where BJJ training actually is in Asheville?

Great article, Preston seems like an excellent role model.