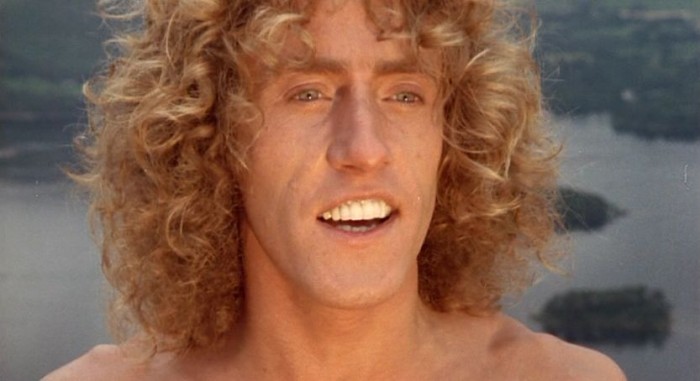

For most people, Tommy (1975) is Ken Russell’s no-holds-barred film version of The Who’s rock opera about a boy traumatized into a state of being deaf, dumb, and blind—and his “amazing journey” to enlightenment and salvation. For me—perhaps because it was my introduction to Russell—Tommy, will always be not just my favorite Russell film, but simply my favorite film. I’ve written about the film many times—most recently when the Asheville Film Society brought in the newly restored version in 2010. I’ve seen the film well into the triple digits in the past 37 years—perhaps most memorably sitting next to Ken Russell in 2005 when he sang along with entire film and occasionally called out when old friends appeared on the screen (“There’s Ollie!”). And you might well think that I’m Tommy‘d out, but I’m not. I find, in fact, that I haven’t even run out of things to say about it—in part because of things other people have said to me, both pro and con. The most recent was on the night Russell died. His wife, Lisi, remarked—about people who don’t like the film or think it a lesser work—that it was really “Ken’s story,” a kind of allegorical cinematic autobiography. I’d never thought of it in quite those terms, but upon hearing that, I realized that in many ways she was on the money. In fact, looking at the film in that light answers many of the criticisms I’ve heard leveled against it. Any retrospective that doesn’t include this film is doing something wrong. Despite the fact that it uses pop culture material for a base (something some Russellites insist on holding against—just as they hold its PG rating against it, and the fact that it made money), it’s a film that is incredibly central to Russell’s work overall—and one of his most accessible to the uninitiated.

One of the more curious things I heard from a detractor was that the film indicated that “Ken Russell hates England.” I was astonished to hear this, because I’ve always found Russell to be the embodiment of the British filmmaker—that he’s almost aggressively English. He never tried to hide it. Even when he made the very American Crimes of Passion (1984), he made it as the outsider Brit looking in. It was also one of those situations where you can’t think of what to say until hours later, so I think I mostly just looked at the man who said this in utter mystification. Later, it struck me that this is part and parcel of the knee-jerk responses Russell’s biographical films—especially those on composers—sometimes incite. The idea comes up that Russell hates a composer—let’s say Tchaikovsky—because he shows some of the uglier aspects of his life. But that isn’t the case at all. He simply refuses to be blind to the shortcomings.

The exact same thing is in operation with the portrait he offers of certain type of British life. Is he out to poke fun at that venerable British institution of the holiday camp with its carefully regimented and unifrom notions fun? Of course, he is. How is it possible to look at it and not find it ridiculous? And how else do you present such peculiarly Brit things as driving to the seaside only to sit in your car and look at the beach through the windshield? (And, yes, it does indeed happen. And, no, despite what you may have read on the internet, according to Russell that is not John Lennon in the car.) There’s also a tendency to generally send up the middle class British—something Russell himself was a product of, and something he largely escaped. (Every so often he’d say something or do something or like something that would forcefully remind you of his background.)

Does any of that mean he hated England? If he did, why didn’t he go to Hollywood? At the very least, why didn’t he seek out some haven from Brit taxes? The answer is pretty obviously that he didn’t hate England at all. Was he amused by it? Perplexed by it? Sometimes even disgusted with it? Of course, he was. Who here hasn’t felt that way about their own country at one time or another?

Most of the film’s targets, in fact, are pretty universal—at least as concerns western civilization. Phony faith healers, latching onto false gods, bogus religions, deifying pop stars, materialism and conspicuous consumption are hardly intrinsically British. In many ways, they might be seen as more American—though because Russell was a British filmmaker working from a work by another Brit, Pete Townshend, and making a British movie, the flavor was decidely and rightly British.

Taking Lisi Russell’s idea of Tommy as autobiographical is an intriguing and profitable notion. In so many ways, it’s a perfect fit—even if in coded form and perhaps more in spirit than in fact (which is exactly what Russell once said to me about his actual autobiography). Some of the references are obvious. For instance, Uncle Ernie (Keith Moon) has a clear cross-reference to young Ken being molested in a movie theater. (I’ve never entirely bought that it was during Pinocchio (1940) as he claimed. That strikes me as a title chosen to make a joke something other than his nose growing. But, hey, it makes for a nice embellishment that sounds good regardless.)

Similarly, the TV commercials for baked beans, detergent, and chocolate that are parodied in the “Champagne” scene obviously chosen because those were the very products that Russell directed commercials for early on in his career before he decided the job was “too obscene.” In fact, it was when it was decided to force soap bubbles up through a drain and then print the film backwards to demonstrate how the bubbles went down the drain (which they would not do) that he quit. Showing these products literally “vomiting” into a person’s home was payback. That Russell later claimed that the source of the scene was “genius” doesn’t change that—nor does it make his answer wrong.

Other things are not so obvious perhaps. The shot of Nora (Ann-Margret) eyeing her chauffeur from the balcony is almost certainly a jab at Russell’s then-wife Shirley, who was having an affair with Russell’s driver. The overall idea, though, of a withdrawn child finding something within himself is key. I never heard—nor have I heard of—Ken Russell say anything against his parents, but it’s hard not to imagine that the situation was at least a little like that which is expressed in Bill Condon’s Gods and Monsters (1998) where an earlier British filmmaker, James Whale (Ian McKellen), says of his parents that their comprehension of him was “as if a family of farmers had been given a giraffe and didn’t know what to do with him.” I think there’s something of that connection here with parents that, try as they might, can’t really reach their son.

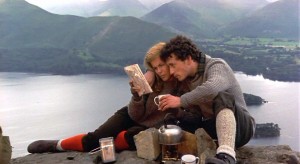

You can get glimmers of Russell’s growing dissatisfaction with his adopted Catholicism in the film’s takes on organized religion—both bogus and real. Was Ken Russell ever beaten up or roughed up as a child in the way Tommy is by Cousin Kevin (Paul Nicholas). I’ve never heard that he was, but it hardly seems unlikely since he was “different” and, in his own word, “solitary.” And, of course, it’s impossible not to connect the fact that the film’s most idyllic moments are the beginning and end—the English Lake District, which had answered things in Russell’s mind more than any religion ever could. There he found the pantheistic idea more to his liking than any dogma had supplied.

But in so many ways, it comes down to the film’s overall thrust. The film opens with the sun going down on Captain Walker’s (Robert Powell) England. The idyllic—if almost certainly romanticized—time that is going with it happens to dovetail with the end of Russell’s own youth. As is common in Brits of Russell’s generation there’s a tendency to look at the world in terms of pre-WWII and post-WWII—with the former viewed as vastly superior to the latter. But Russell takes that idea and goes it one better. He presents all the post-war era things he finds wanting or even hateful and comes out the other side to find the dawning of a better post-post-war era. It is that world—which is also the world of the Who, rock music, etc.—that the sun is rising on at the film’s end. The sun rises on a world of new possibilities that rejects the failings of that post-war era in favor of an ideal of what might be. (I won’t comment on how that worked out.)

So, yes, it is autobiography—sometimes specific, sometimes allegorical—but still it tells an essential part of the story of the filmmaker himself.

Since I have written so often on this topic, I will direct you to some of those earlier takes:

http://www.mountainx.com/article/8212/Tommy-A-trip-ahead-of-its-time

http://www.mountainx.com/movies/screening_room/2010/cranky_hankes_screening_room_itommy_i_the_movie_—_an_appreciation

http://www.mountainx.com/movies/review/tommy

By the way, I hate that trailer that Mr. Shanafelt put up. If you want a trailer, go to this one:

http://www.tcm.com/mediaroom/video/158110/Tommy-Original-Trailer-.html

You’ve done it again, Young Camel as Yet. Brilliant and spot-on. I could recount the many times I’ve heard T’Other Ken talk about climbing into the Morris cage every night, like Ann-Margret, during the bombing of Southampton (when he was a child of little Tommy’s age). The panic. I agree about the dubiousness of the particular film Pinocchio being the scene of molestation, although the act itself certainly happened. Pre-, post and post-post: absolutely inspiring conclusions. No wonder T’Other Ken liked your columns best. We pre-, post- and post-post-Russellites salute thee!

The abuse I endured in school is far worse than what was depicted in the “Cousin Kevin” scene.

I’m trying to get a Ken Russell retro going here in Berkeley at the Pacific Film Archive. Which of his films did you show on film, which on video?

No wonder T’Other Ken liked your columns best.

Better than that, I can’t ask.

The abuse I endured in school is far worse than what was depicted in the “Cousin Kevin” scene.

Okay…

Which of his films did you show on film, which on video?

Unless you have access to an old style 35mm two projector set-up that allows you to run archival prints reel-to-reel, you’re going to find that DVD is probably all you’ll get — assuming you don’t know a collector with 35mm prints who will allow them to be hooked together on a platter.