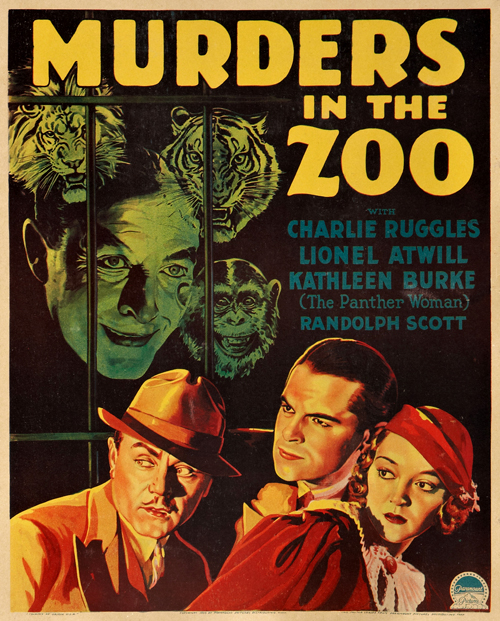

A. Edward Sutherland’s Murders in the Zoo (1933) is from that brief period (1932-33) where Lionel Atwill was a horror star, as opposed to simply being a character actor who often showed up in horror pictures. Just what happened to demote him to the lower levels of casting is unclear, since his earlier movies were good and apparently popular, but after 1933, he was never the big deal he was during this brief period. Actually, in Murders in the Zoo he takes second billing to Paramount contract player Charlie Ruggles, though Atwill is clearly the star. (The studio probably saw more percentage in promoting one of their own.) This time, Atwill is big-game hunter Eric Gorman, who also brings ‘em back alive for the titular zoo. In his spare time, he’s a sadist and occasional murderer of his wife’s (Kathleen Burke, the “Panther Woman of America”) lovers—both real and imagined. When the film opens he’s just sewn together her latest boyfriend’s lips and left him to die in the jungle, then telling his wife that the fellow simply left. (“He didn’t say anything.” What a card.) Back in civilization, her further infidelity sends him over the edge and onto a delirious murder spree with the use of the damndest murder weapon you’ve ever seen. The film is slick, a little bit sick, decidedly odd—and all Atwill’s show. And Lionel Atwill in the full-flower of lecherous perfidy is a kinky joy to behold.

Perhaps the most surprising thing about Murders in the Zoo is its director. To the degree that A. Edward Sutherland is remembered at all today, it’s probably based on the films he made with W.C. Fields. If you’re a little more up on movie history, you might associate him with other light fare, but in any case, Sutherland is about the last person you’d expect to be found making a stylish and grim horror film. It’s quite possible that he was onboard more for Charlie Ruggles’ comedy than for Atwill’s perfid. Then again, anyone who could maintain both a professional and personal relationship with W.C. Fields must have had a slightly twisted sense of humor, which would have served him well for this particular one shot of horror.

Actually, Murders in the Zoo is a film that would probably have been entirely forgotten today had it not found its way into William K. Everson’s Classics of the Horror Film—a typically idiosyncratic Eversonian work that was as apt to spotlight a curio like this as an “acknowledged” classic of the genre. (Occasionally, this was even at the expense of an established classic, which I don’t think is a bad thing. After all, it’s not very likely anyone is going to forget the 1931 Tod Browning-Bela Lugosi Dracula.) And there’s no denying that Murders in the Zoo is as much curio as classic. But what a nifty little curio it is—and one that’s maybe more fun than some films that are more classic.

When we think of 1930s golden-age horror pictures, the natural tendency is to think of those 12 movies from Universal. But Paramount ran them a close second—and in some ways surpassed them by never developing a formula or much leaning on “horror stars.” That was probably not entirely intentional. After their initial stab at horror with Murder by the Clock (1931), the studio was set on the idea of making Irving Pichel (who’d played a murderous moron in that film) into a horror star, attempting to foist him on Rouben Mamoulian for his Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Mamoulian pointed out (rightly) that Pichel might make a fine Hyde, but couldn’t possibly play Jekyll. Fredric March got the part and Paramount seems to have gotten over the idea of a horror star.

Overall, the Paramount horrors were either more fantasies—Death Takes a Holiday (1934), The Witching Hour (1934)—or were in a hardcore mode that presented their horrors straight-up. Murders in the Zoo, though definitely blessed with a sense of not-always-wholesome humor, is definitely in the latter category. This is, after all, a movie in which we’re treated—in the first few minutes—to a graphic close-up of a man with his lips sewn shut. In short, it’s not fooling around. And the grisliness hardly ends there, though that is perhaps the most shockingly in-your-face moment. The ending, however, is not to be sneezed at by any stretch of the imagination.

The gruesomeness extends to every aspect of Atwill’s bravura performance. He stops short of outright ham, but there’s never any doubt that the man is enjoying every moment of his generally transparent villainy. In fact, of Atwill’s brief flirtation with stardom, his Eric Gorman here is easily the most completely unsympathetic and utterly reprehensible of all his characterizations. It’s also the most brazenly pre-code, since there’s nothing like a spot of offing his wife’s boyfriends for getting his amatory juices flowing. His two best—and best remembered—early ‘30s horrors may be Doctor X (1932) and Mystery of the Wax Museum, but this is easily his most deliciously despicable. And he gets a comeuppance that’s fully worthy of it.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.