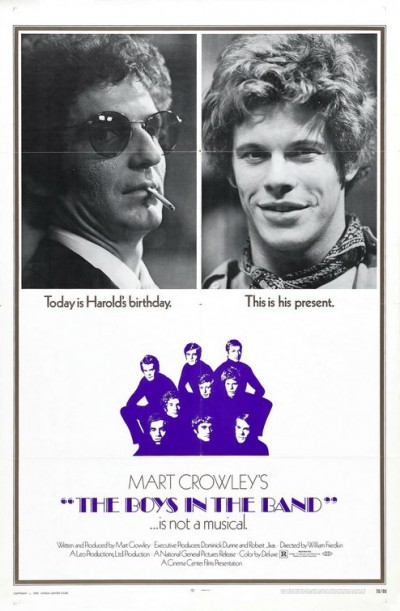

It’s become OK to like William Friedkin’s The Boys in the Band (1970) again. Which is good news, because this may well be Friedkin’s best film. The business of shoving the film into the closet — because its view of gays was “dated” — was always a little silly and more than a little ironic. It’s a very intelligent film version of Mart Crowley’s 1968 Off-Broadway play that was originally considered to be a huge breakthrough in terms of dealing with gay characters. (”The Boys in the Band Is Not a Musical,” the tagline tells us.) Unfortunately, both the flamboyant portrayal of Emory by Cliff Gorman (one of the actors who wasn’t actually gay) and the whole concept of the self-loathing gay man came to be seen as derogatory. Both the play and film were consigned to the vault of cultural relics we no longer spoke of. Fortunately, over the last several years the attitude towards The Boys in the Band has changed, allowing it to take its proper place as a vital, moving and frequently hysterically funny portrait of its time — and we’re even allowed to admit that there’s still a good bit of truth to be mined from it. The premise places the viewer as spectator at a gay birthday party that turns pretty nasty — and revelatory — when the supposedly/maybe straight old college friend of the party-thrower shows up unannounced. Powerful, painful, and blessed with endlessly quotable dialogue.

Apart from the gloriously cinematic opening (using the 1968 Harper’s Bizarre version of Cole Porter’s “Anything Goes” — with a lead-in from Porter’s own recording), there is no obvious attempt to “open up” the play. That opening, however, was a masterstroke in that it managed to not only draw most of the characters in broad outlines, but it even cleverly worked in Emory’s inspiration of picking up a street hustler, “Cowboy” (Robert La Tourneaux), as a suitable birthday surprise for Harold (Leonard Frey). (The opening also illustrates that the power of all good swear words is that they’re easily lip-read.) Otherwise — exempting a few build-up bits — the film is virtually a straightforward presentation of the show, but that doesn’t mean it’s in any way uncinematic, so disabuse yourself of any horrors of two hours of stagebound tedium. Far from it. John Robert Lloyd’s set design for Michael’s (Kenneth Nelson) apartment is part of the reason, but it’s really Friedkin’s handling of the material that keeps it moving and cinematic. God knows, few things are more flamboyantly cinematic as the all important entrance of Harold — pure cinema, but of the most theatrical kind, which is just right for the film.

If anything, the stage nature of the movie lies in its intricate dialogue. Don’t get me wrong, it’s terrific dialogue — I’ve been quoting it for years. (Indeed, my cover will be completely blown for me with friends of mine seeing this for the first time and encountering such things as, “That’s French with a cedilla,” “You’ve had worse things in your mouth,” “Who is she? Who was she? Who does she hope to be?” and the all-purpose, “Well, that wasn’t as much fun as I thought it would to be.”) There is, however, no denying that it very often sounds like the dialogue in a play. Real life simply doesn’t sound like this — and I’m tempted to add, more’s the pity.

The hook to the work lies in the fact that it let the audience into a world with which many were completely unacquainted — and it did it with surprising candor. Consider the early exchange between party-giver Michael and his sometimes sleepover buddy Donald (Frederick Combs) discussing the impending party. “If there’s one thing I’m not ready for it’s five screaming queens singing ‘Happy Birthday,’” grumbles Michael, further elaborating on the guest list with, “It’s the same old tired fairies you’ve seen around since the day one. Actually, there’ll be seven — counting Harold and you and me.” Donald takes exception to this, “Are you calling me a screaming queen or a tired fairy?” Michael relents and corrects himself, “I beg your pardon. There’ll be six tired, screaming fairy queens and one anxious queer.” The play and the film pull no punches in this area.

But it’s less the hook that draws the viewer into the story and holds their attention than it is the questions it raises and leaves unanswered. Here we are forty-odd years later and people are still debating whether the suddenly intruding straight friend Alan (Peter White) is really straight or deeply closeted. Is his rage against the effeminate — and deliberate straight-baiting — Emory really rage against himself? What is the reason Alan so desperately needs to see Michael in the first place? There are no answers, but the questions linger in the mind long after the brilliantly bitchy barbed banter has been relegated to the sidelines. The same could be said of Michael’s birthday gift to Harold, which we’re told is a photo of Michael in a silver frame with an inscription (“just something personal”). We never see, we never know, but it has a clear impact on both Harold and Michael that suggests their relationship is much deeper than we’ll ever see. It is these unanswered and unanswerable questions that keep the film constantly relevant — and that make it a more haunting work than its brittle surface suggests.

The story is simple enough, but it has depths that are more evident on repeat viewings. The increasingly nasty, bitchy quality of Michael is better explained when you start paying attention to its progression as it relates to him lapsing into drinking (it’s established that he’s quit) during the course of the film, and the impact that Alan’s untimely arrival has on him. Michael is really the center of the film — and is clearly a character grounded in playwright Crowley himself with its references to being from Mississippi and incorporating Crowley’s own father’s actual dying words into the dialogue as the last line. To understand the film, you have to understand Michael — and you have to understand where gays stood at the time of its creation.

There is an inevitable sadness that hovers over the film these days in light of the actors in the film who have succumbed to AIDS in the intervening years — Kenneth Nelson, Frederick Combs, Keith Prentice, Robert La Tourneaux. Touchingly, it was the straight Cliff Gorman and his wife who took care of La Tourneauux (who died at 41) in the last years of his life. Things like this are part of the reason why I think it is so terribly wrong-headed to relegate the play and the film to some kind of relic status that we shouldn’t talk about anymore in our supposedly more enlightened era.

The Asheville Film Society will screen The Boys in the Band Tuesday, March 20, at 8 p.m. in the Cinema Lounge of The Carolina Asheville and will be hosted by Xpress movie critics Ken Hanke and Justin Souther. Hanke is the artistic director of the A.F.S.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.