- Mother/son team: Gabe Dunsmith and Lee Ann Smith campaign to increase awareness about CTS Corp.’s failure to clean up a contaminated south Asheville site.

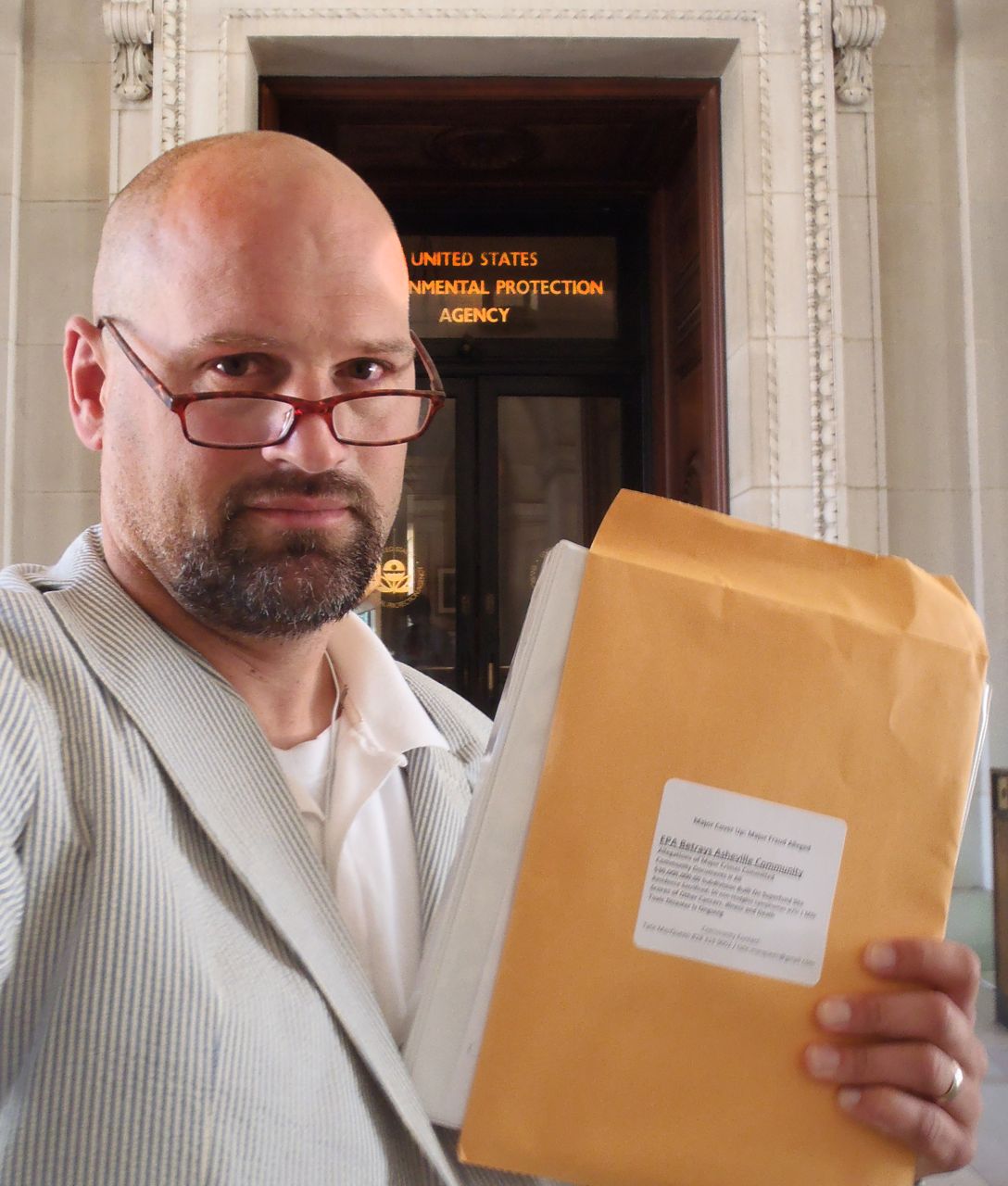

- Frontal assault: Tate MacQueen has taken the fight to Washington, D.C., alleging misdeeds on the part of U.S. Environmental Protection Agency officials charged with protecting human health in the CTS case.

“No man can tame a tiger into a kitten by stroking it.”

— President Franklin D. Roosevelt, 1940

Lee Ann Smith’s and Tate MacQueen’s methods may differ, but their aim is the same: help their south Buncombe friends, families and neighbors obtain clean air and water. (photo of Gabe Dunsmith and Lee Ann Smith by Bill Rhodes)

Five years ago, Mountain Xpress broke the story about untreated contamination linked to a former electroplating plant on Mills Gap Road (see “Fail Safe?” July 11, 2007). Both Smith and MacQueen live about a mile from the property, where the Elkhart, Ind.-based CTS Corp. operated a facility for more than 25 years. Both are teachers with a lengthy history of involvement in grass-roots efforts related to the site.

And despite some forward movement in the long-running case, they’re not backing off.

“We want a full-scale cleanup, and we want clean water, air and soil so people won’t continue to be exposed,” says Smith. Her son, Gabe Dunsmith, who’d often played in a stream that flows from the site, developed thyroid cancer at age 11. It’s hard to prove, and official health studies in the CTS case were inconclusive, but Smith believes her son’s illness is linked to trichloroethylene, a highly toxic chemical used at the old plant that’s still found in extraordinarily high concentrations in nearby springs and wells.

“The source is very strong and isn’t evaporating,” says MacQueen, citing recent test results that show possible contamination in his own neighborhood. He says he also knows of 50 cases of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma — as well as other cancers and serious illnesses — affecting friends and neighbors who unknowingly used contaminated water for years. “This is an issue of human health and environmental justice,” he declares.

Keeping the pressure on

MacQueen teaches U.S. history at Owen High School, and when asked about his aggressive approach to the CTS case, he quotes President Roosevelt’s 1940 call to arms about taming a tiger. “We are defending our right to clean water and clean air,” says MacQueen.

Since learning about the contamination four years ago, he’s developed an encyclopedic knowledge of the case, citing test results, letters and other documents the way most folks would rattle off their kids’ names and ages. That knowledge, he says, provides leverage.

He’s helped bring a lawsuit against the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, accusing officials of negligence and possible fraud in their handling of the case. MacQueen also regularly assails EPA officials with lengthy, passionate emails calling for action, not more promises. Armed with knowledge, he continues to enlist local, state and federal elected officials in the fight. (photo courtesy of Tate MacQueen)

He’s helped bring a lawsuit against the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, accusing officials of negligence and possible fraud in their handling of the case. MacQueen also regularly assails EPA officials with lengthy, passionate emails calling for action, not more promises. Armed with knowledge, he continues to enlist local, state and federal elected officials in the fight. (photo courtesy of Tate MacQueen)

“In 1987, the officials knew about the contamination. If CTS were ever going to do the right thing, it would have been done,” asserts MacQueen, who in late June traveled to Washington, D.C., to keep pushing for significant action. “And the EPA could have done something a long time ago.”

Getting a federal Superfund designation in March was an accomplishment, he acknowledges, but it will entail more studies taking still more time, and in the end, it will address only ground-water contamination — not air or surface water. Meanwhile, as part of a related agreement with the company, the EPA has asked residents to agree to have whole-house water filters installed in their homes this summer. That’s a “temporary fix” that isn’t even the right filter for the job, says MacQueen, but if it becomes the de facto final remedy, it’s an easy out for both CTS and the EPA. “The EPA is driving the getaway car, and CTS is in the back seat with their feet propped up,” he maintains.

MacQueen wants water lines extended to serve affected residents. He wants the source cleaned up and removed, which he says the EPA has the authority to mandate. And he wants the agency’s officials held accountable for the mistakes they’ve made over the last 25 years.

MacQueen, who also coaches and plays soccer, specializes in the defensive positions that keep the other team from taking shots. “We will get city water, and we’re going to leverage back the truth,” he vows.

Targeting CTS

Smith, a teacher in south Asheville, prefers to keep the focus on CTS. Some days she looks at her students and “It just hits me: I hope none of these kids gets sick.”

When her son, now a sophomore at Vassar College, was diagnosed with thyroid cancer, doctors asked if the family had ever visited Chernobyl, the Ukrainian city where a catastrophic 1986 nuclear accident released massive quantities of radiation. They’ve never been there.

“We want a full-scale cleanup, and we want clean water, and of course, clean air and clean soil so people won’t continue to be exposed,” Smith explains. “We are working on a campaign to start hitting CTS and letting them know they need to … get this cleaned up.”

On July 4, as cars whisked by just a few feet away on Mills Gap Road, mother and son hung homemade signs on the property fence: “CTS + TCE kills.” They’ve also posted skull-and-crossbone images alongside the Superfund notices. “The signs that indict CTS tend to get taken down quickly,” says Smith, but, “It’s cheap and effective.”

For Smith, it was a “happy day” when Buncombe County contractors demolished the remaining, vacant structure last year and hauled away the debris. “It’s easy to think, ‘The building is gone; everything is OK,’” she observes. But her signs remind people that things aren’t OK.

A CTS-funded soil-vapor-extraction project removed 6,000 pounds of toxins between 2006 and 2010, yet tests earlier this year still show high levels of TCE and other contaminants. “There is still no comprehensive plan for cleanup,” notes Dunsmith, who’s also researched the case extensively. “CTS has never shown any interest to act on behalf of human health; we don’t trust them. … We want source removal.”

Like MacQueen, Dunsmith and his mother see the water-filter program as an interim, Band-Aid measure at best. But they urge people to direct “antagonism toward CTS,” arguing that “having the communication lines open with the EPA is a powerful way to put pressure on them to do the right thing.” Of 129 homeowners eligible for the filter systems, 56 have agreed to have them installed, Smith reports — but almost 90 percent say they ultimately want public water.

Those numbers, she says, helped persuade the Buncombe County commissioners to apply for a $4 million state loan that could pay for extending water lines to those residents.

Meanwhile, residents fear the filter system could “become sort of an excuse to not clean up” the CTS site, as has happened in other contamination cases, says Katie Hicks, assistant director of Clean Water for North Carolina, a statewide nonprofit with an office in Asheville. But, “as long as there’s continuing pressure toward [real] cleanup, this interim measure shouldn’t preclude that,” she maintains.

A small hit

The difference in tactics “doesn’t mean we’ll agree with what the EPA is trying to do or always agree with their vision of the site,” Dunsmith explains. But he believes the bull’s-eye should be squarely on “the polluter who made this mess in the first place.”

To that end, Dunsmith has sent emails and posted Facebook comments, urging businesses that supply or receive supplies from CTS to learn what the company has done. “I didn’t get a response from Toyota, [but] other big companies are on the [supply chain], and there is a potential for a lot of people to see my posts,” he says.

Smith, meanwhile, mentions a small success: With help from local engineer Pat Dunn, this March local residents won a decision by the North Carolina Board of Examiners for Engineers and Surveyors that ordered CTS staffer Marvin Gobles to “cease and desist” providing advice and reports concerning the Asheville site. In 1987, Gobles wrote to Mills Gap Road Associates, a local developer that was interested in buying the property, declaring the site to be in “environmentally clean condition.” The developer later sold most of the parcel, which became Southside Village, a residential complex.

The company and the EPA “had been depending on his [opinion] for 30 years to make life-and-death decisions, [but] he was not licensed in this state,” says Smith.

Getting him removed from the case, she says, “was a direct hit on CTS — a small hit in the gut.”

The real hit, a true cleanup, would be expensive, Smith concedes, though she’s quick to add, “Human life is much more precious.”

For more information, links to documents and background, visit http://avl.mx/au to view key documents in the CTS case. For the latest Xpress coverage of the issue, go to www.mountainx.com/cts. To view a timeline of the CTS case, click here.

Mountain Xpress first covered this story in 2007, when residents brought to light the extent of the contamination (see “Fail Safe?” July 11, 2007).

Margaret Williams can be reached at 251-1333, ext. 152, or at mvwilliams@mountainx.com

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.