What are we talking about when we talk about sustainability in Asheville? Do we mean cleaner air and environmental preservation? More city parks, better education, access to good food and quality housing? All these things help make a sustainable, happier, healthier city, but history shows that the vision of a prosperous city often fails to include all the residents.

For low-income communities, people of color, women and other minorities, basic desires like achieving workplace equality or attaining safe, affordable housing may be more difficult. Access to green spaces is often more limited in low-income neighborhoods; children of minorities often face increased discrimination in schools.

“There is a point to which people can be agents of their own life and their own change,” says Deborah Miles, executive director of the Center for Diversity Education at UNC Asheville. “But after a while, if they and all the people around them are acted upon, instead of being their own agents, then their feelings of self-esteem, of self-efficacy, the belief that they have some control over what happens in their life, diminishes.”

If we think of sustainable systems as diverse but interdependent parts of a whole, then the disempowerment of minorities is not only a danger for the health and well-being of those communities: Miles cautions that without all the voices of a diverse citizenry, we diminish the power of a city’s democracy and its overall health.

The legacy of separate but equal

Like many cities throughout the country, Asheville has its own dark history that includes subduing the power of minority communities.

“We know from eyewitness testimony that Asheville was a segregated city,” says Miles. “Restaurants, hotels, buses, pools, school, libraries — everything.”

Miles says segregation in Asheville, as in most of the country, was carried out through redlining, named for the literal act of drawing a red line around communities on a map — communities where financial institutions denied service, usually African-American or low-income neighborhoods. Segregation was reinforced from the 1940s through 1960s as part of urban renewal, when cities improved tax bases by installing new transportation corridors and expressways, often by sending the new construction through low-income communities and uprooting African-American neighborhoods.

“Asheville is a microcosm of all the federal legislation, all the banking practices, all the social experimentation that occurred throughout the country,” Miles says.

Though some of this effort may have been intended to remove substandard housing stock, Miles says, the actual result was destruction of the social fabric of nearly all of Asheville’s African-American communities.

“The concern always seems to be, ‘What is best for more well-to-do citizens?’ rather than ‘How can we live together?’ or ‘How can we have good education, good air, access to healthy food, for everyone?’” says Miles.

The effects of urban renewal can be seen in Asheville’s East End neighborhood, which includes Eagle and Market streets,as well as the YMI Cultural Center. For the first half of the 20th century, East End was the commercial hub for Asheville’s African-American community, with about 70 residences and about 50 small businesses.

“Urban renewal splintered community,” says Stephanie Swepson-Twitty, president and CEO of Eagle Market Streets Development Corp. “They didn’t just tear down bricks or mortar, or tear down physical structures. They tore down the fabric of the community, so that those folk who lived down the street and could shop in their community no longer could do that. Those folk lost their identity.”

Swepson-Twitty says the loss of housing stock in East End and other neighborhoods left many in those communities with no other option but public housing. And public housing, Swepson-Twitty says, was a place where fear, insecurity and despair became concentrated and strengthened.

“You didn’t create a better life by putting people in these pockets where all the same ideas and mentalities and fears coexisted,” Swepson-Twitty says. “People didn’t feel a motivation to come out of that situation.

“The tragedy of urban renewal was that it took away people’s hope,” she continues. “The family that had the corner store lost their livelihood. The neighborhood that was immediately adjacent lost its connection to this neighborhood, and so they couldn’t grow together.”

Undoing the damage of urban renewal has been an ongoing process, and Swepson-Twitty says that for the last 25 years there have been efforts to revitalize the area around Eagle and Market streets known as The Block, including the formation of the nonprofit Eagle Market Streets Development Corp. in 1994.

“It’s speculative, but if this hadn’t happened, I think now we would be looking at how to improve ourselves, rather than how to reinvent ourselves,” Swepson-Twitty says.

In late 2013, the EMSDC received funding to partner with another local nonprofit, Mountain Housing Opportunities. Together, the organizations developed a new mixed-use space called Eagle Market Place. The project will include 62 workforce-affordable rentals, in addition to retail and community space. But as much as the new project is about revitalization of the neighborhood, Swepson-Twitty says, the vision is rooted in collaboration.

“We, as a culture, had this sense that we could be ‘separate but equal,’” Swepson-Twitty says. “Well, that won’t work. The resources need to be shared by all of us, in order for all of us to participate.”

Eagle Market Place will lease space to “strong businesses” from across the city and across the region, Swepson-Twitty says. She envisions a future for The Block that is vibrant and economically healthy, while making the neighborhood a shopping, entertainment and cultural destination for all the residents of Asheville and its visitors.

“In order for us to be whole, we have to be inclusive,” she says. “We have to be willing to say, regardless of our ethnicities, if you bring value to the community, then you have a place in the community.”

The economics of diversity

When we think about diversity and sustainability, it’s important not to overlook the practical side — the dollars and cents of the equation.

“I think Asheville does a great job at looking at the environmental concepts behind sustainability, but we do a poor job looking at the economic concepts behind sustainability,” says Mark Hebbard of Just Economics.

Hebbard uses the example of natural systems, where you see diverse systems working in harmony and rarely find monoculture.

“If you come in and plant one crop, the quality of the soil and the surrounding environment suffers,” Hebbard says. “Similarly, if we had only huge, corporate establishments without the small businesses, it wouldn’t be too long before there wouldn’t be very many small businesses left or even people interested in starting small businesses.”

How does that relate to diversity? When we look at the structure of many national corporations, Hebbard says, we’re less likely to see women and minorities in the upper ranks. However, when we look at Asheville’s small, locally owned businesses, particularly those that have received Living Wage Certification from Just Economics, the opposite seems to be true.

“The Living Wage Certified employers that we have, there’s a lot of diversity in there,” Hebbard says. “We have a lot of women- and minority-owned businesses. I think [it’s] a lot higher representation than the overall percentage here.”

Just Economics began the Living Wage Certified program in 2008. The organization promotes education about the importance of paying a living wage and has certified more than 330 businesses, making it the largest living-wage certification program in the nation. And that’s important, Hebbard says, because in Asheville, as in the rest of the nation, women and minorities are typically paid less.

But there’s another benefit to supporting small businesses, Hebbard says: Small-business owners are more likely to live in the same communities as their employees, giving them a personal investment in the future of their employees and their neighborhoods.

“When the owners of the companies actually socialize with their employees — when they shop at the same stores, when they see each other on the street — when that hap- pens, the employers understand the plight of their employees better,” Hebbard says. “When you have a separation between the owners of the company and the employees, it becomes easier to look away or to not feel a connection to your employees.”

That’s why it’s important to support minority-owned businesses in minority communities, Hebbard says. Through its Voices Program, the nonprofit aims to build leadership among low-wage workers and low-income persons, which often means minorities and women.

“Instead of having people in privilege advocate for people in poverty, we want to empower folks in poverty to get back in the community to advocate for themselves and others like themselves,” Hebbard says. “To build up their communities and to direct and drive our work.”

Ending self-segregation

While there may be many efforts underway to overcome the history of separate-but-equal in Asheville, there are communities still experiencing the kind of persecution that seems to be plucked from the pages of a history book — including racial profiling, sexual harassment and wage theft.

Mirian Porras works at Nuestro Centro, a community outreach center whose stated goal is helping people affected by racism, classism, homophobia, sexism and unjust and corrupt economic policies and political systems. The center offers English as a second language (ESL) classes and connections to services such as food pantries and health clinics. The staff facilitates communication for those who feel uncomfortable with the language barrier and works to foster relationships between the Latino community and local law enforcement. They also work to stop the exploitation of their community, which Porras says is a bigger problem than many may realize.

“It’s really hard to stand up for your rights when you don’t speak the language, because you will be told, ‘You don’t understand what’s going on,’” Porras says. “That’s a big excuse. There is a lot of this going on in Asheville, but people don’t know. Many in the Latino community don’t want to speak. They are afraid and they stay silent for a long, long time.”

Porras tells the story of a woman who sought assistance at Nuestro Centro after being the repeated target of racial epithets and sexual harassment in her workplace. Like many in the Latino community, Porras says the woman chose to “self-segregate,” focusing on her work and withdrawing from her co-workers.

“When you work 10 hours, more, every day, eventually that makes you feel alone and depressed,” Porras says. “It’s not a way to live.”

What made matters worse is that when the woman spoke to her manager about the situation, she was told that because she didn’t speak English, she simply misunderstood what had happened. Porras says that’s an outcome all too common and one that leads many in her community to leave abuse unreported.

“Even if you have a barrier with the language, you know when you’ve been discriminated [against],” Porras says. “You know when you’ve been sexually harassed. You know when you’ve been exploited. If your manager doesn’t want to hear it, find some- one who does. Do not remain silent.”

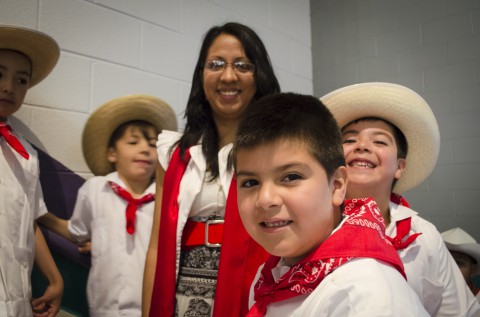

Porras says the work of Nuestro Centro is out- reach, letting Latinos know they are not alone. The nonprofit also helps victims of sexual harassment and wage theft to feel safe and have their complaints heard. Nuestro Centro also works to get Latino parents more involved with local schools and holds cultural days to educate non-Latino children about the customs of their fellow students and remove what Porras calls “seeds of hate” from a younger generation.

“When you begin to link people, you erase the segregation of the Latino community,” Porras says. “It’s really hard to link communities, but it’s a basic need.

“We want the rest of the community to know us, so our children can live in peace,” she continues. “We don’t want to live in a place that is unsafe or filled with prejudice.”

Moving Forward

Looking at Asheville’s history, it’s clear the movement toward a more sustainable future has come a long way. But have we succeeded in creating a healthy, happy city for all the residents?

Problems still exist in Asheville. Miles points out that for residents of many low-income neighborhoods, such as Pisgah View Apartments, access to green space still means having to cross high-speed, high-traffic roads.

And the evidence of generations of white flight is still visible in Asheville City Schools. In a city that is about 13 percent African-American and about 80 percent white, about 40 percent of the students in Asheville City Schools are African-American, says Miles. Furthermore, children of minorities are more likely to face bullying, especially Latino children, she says. Porras also cautions that many Latino parents who would otherwise be involved in local schools feel unwelcome by other parents because they do not speak English.

So what can individuals do to reach across barriers of race, gender or income? Start simple, Miles suggests.

Talk to your cashier at the checkout counter and say, “Thank you.” Build relationships outside your peer group. Increase your cultural awareness by watching TV shows or reading magazines designed to appeal to a different demographic. Go to cultural festivals. Donate money to community groups working to revitalize their neighbor- hoods. If you’re an employer, look at your pipe- lines: How do you recruit your employees and are you always pulling from the same sources?

“Small encounters change lives,” Miles says.

Porras adds that encouraging communication is a giant step, and while the Latino community should work to learn English, we should also encourage the rest of the community to learn “even a little bit of Spanish.” It’s also important, she adds, that all members of the community report sexual harassment, wage theft and racial profiling when they see it, whether directly affected by it or not.

“We have to listen to each other, to be empathetic with the problems of the Latino community, and participate,” Porras says. “All the communities in Asheville should work on tolerance.”

For Swepson-Twitty, a sustainable city can only be achieved by holding onto a vision of collaboration and inclusiveness.

“A healthy, sustainable community is inclusive — meaning there is a voice for all the people who live there, work there, enjoy entertainment or go to church there,” she says. “You and I are much better together than we are separately.”

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.