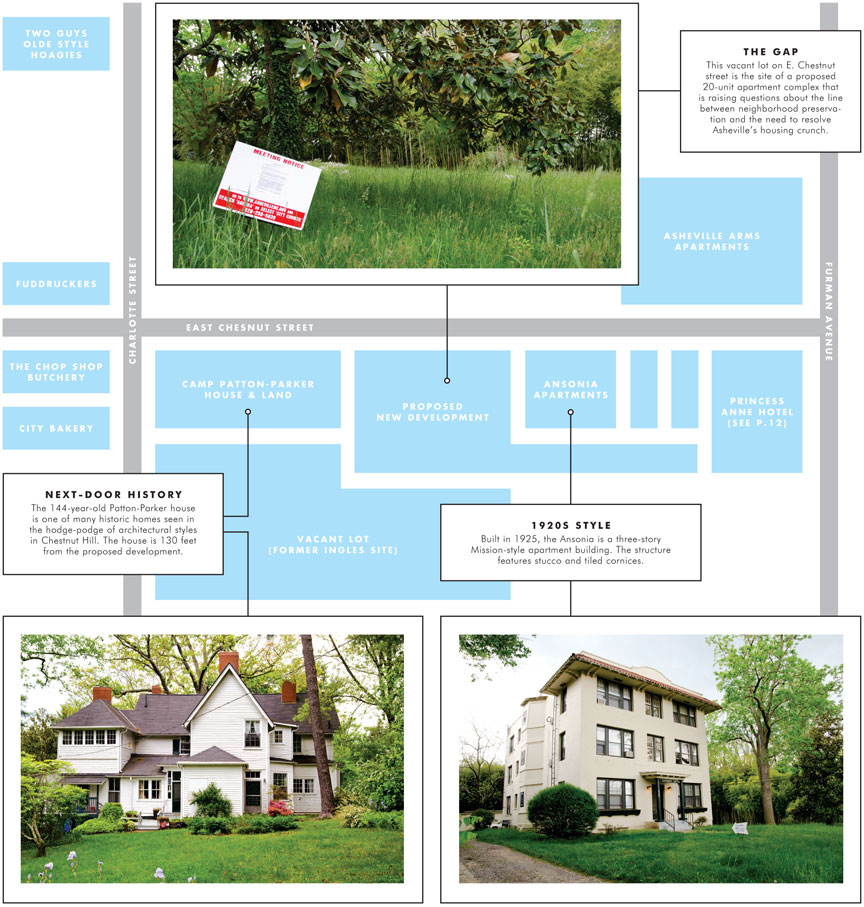

- The gap: This vacant lot on E. Chestnut street is the site of a proposed 20-unit apartment complex that is raising questions about the line between neighborhood preservation and the need to resolve Asheville’s housing crunch. Photos by Max Cooper

- Fighting pressure: Jack Thomson, executive director of the Preservation Society of Asheville Buncombe, sees fighting the Chestnut project as a way to curb “jarring” density changes in “fragile” historic neighborhoods near downtown.

- Unheard voices: Lindsey Simerly, chair of the city’s Affordable Housing Advisory commission, believes it’s time to start listening to working Ashevilleans who need affordable housing.

- Next-door history: The 144-year-old Patton-Parker house, one of many historic homes in the hodge-podge of architectural styles in East Chestnut. The house is 130 feet from the proposed development.

- Best use: Architect Richard Fort, one of the developers of the E. Chestnut Street proposal, says density is needed and neighborhood input will improve the development, “but some people just won't like change, whatever form it takes.”

Walk a short way on East Chestnut Street and the traffic on Charlotte fades into a distant hum. Historic structures like the Princess Anne Hotel rub shoulders with 1970s- and 1920s-era apartment buildings of various vintages, as well as assorted Arts and Crafts bungalows. The sparkling grass reflects the city’s cool, rainy spring.

Midway down the block, a white sign emblazoned with “Meeting Notice” in red marks a vacant lot that’s overrun with grass, bamboo and wildflowers. The lot is an anomaly in the mostly well-tended Chestnut Hill Historic District. Less than a half-acre in size, it might make a strolling stranger pause for a second, or children explore the grounds till their parents called them home.

The city’s informational sign provides the only hint that a development is planned here, that this unassuming patch of ground actually embodies a critical debate confronting Asheville: How does a rapidly changing city balance the unique virtues of local character and the pressing need for more housing?

Fighting sprawl

What's causing all the fuss is a proposal by PBCL, a local sustainable-development company, to build 16 new two-bedroom apartments on this lot and an adjoining one the company also owns. Renovating four small, one-bedroom apartments on the latter parcel would bring the total to 20 housing units on less than an acre.

The contemporary-style building would feature off-street parking and a LEED Silver sustainability rating. The existing one-bedroom units would be offered at no more than $661 a month, the maximum amount the city considers affordable housing. The rent for the new construction hasn’t been set yet.

“We take vacant lots and, by increasing the density, make better use of them,” PBCL architect Richard Fort explains. “It doesn't cost the city; the utilities are already there. Folks that live here may be able to walk to work, certainly bike. It's a smart thing to do: It's an effort toward reducing sprawl.”

Best Use: Architect Richard Fort, one of the developers of the E. Chestnut Street proposal, says density is needed and neighborhood input will improve the development, “but some people just won’t like change, whatever form it takes. Photos by Max Cooper.

But PBCL needs the parcels rezoned from RM16 to Urban Residential District to allow a larger building that could be sited closer to both the street and the adjacent Camp Patton-Parker House (see sidebar, “A Sense of Place”). The 144-year-old home, which has been in the same family for seven generations, sits 130 feet from the property line, notes Fort.

In dialogue with planning staff over the past few months, Fort and his partners have touted the project’s congruence with the city’s 2025 Plan, which lays out broad goals for future development. One of them is increasing density around downtown and along transit corridors.

“Our sustainable development,” architect Chad Roberson wrote in answer to a city staffer’s questions, “is designed to serve the community for generations.” The project would fit right in, he maintains.

Size matters

Some residents, however, strongly disagree.

“It's a very active neighborhood. People wave to each other on their front porches,” says Mark DeVerges, who lives nearby. “Everyone's actually excited something's going to be built. But unfortunately, the developers are going forward with something that doesn't fit. I'd like the developer to be more respectful of the surrounding property.” DeVerges says he’s OK with denser development on the site, but he believes the size, scale and design of the proposal are inappropriate. And if it goes forward in its current form, he’ll fight it.

At two community meetings held by PBCL and in emails to city staff, other residents raised similar concerns. Some said the four-story building would be too tall or would contain too many units.

“I think the building will be overwhelming on the lot and street,” neighbor Bill Chase wrote to city staff.

Resident Jessica Bernstein, who works in the city Planning Department, said she’s comfortable with the density but feels the project's design is “out of character with the styles of the historic homes we enjoy.” Others likened it to the Aloft Hotel on Biltmore Avenue or even to a cruise ship docking in the middle of their street.

Still others, however, applauded the project.

“I am VERY in favor of the proposed development on Chestnut Street,” wrote Robin Raines, an architect who lives around the corner on Furman Avenue. “I love the design, welcome the contemporary style to a neighborhood of mixed quality and styles, and look forward to a new texture on the street.”

But for Jack Thomson, executive director of the Preservation Society of Asheville and Buncombe County, initial concern about the impact on the Patton-Parker House has grown into a full-blown determination to halt the development or force it to scale back. To that end, he’s helping neighboring property owners ready their protest petitions.

“Growth for growth’s sake is the ideology of a cancer cell. If the only reason to grow is because we think it has to happen, we’re not looking at the full equation.” — Jack Thomson, Preservation Society of Asheville and Buncombe County

“The size of the project is too far out of character with the neighborhood, which is a nationally registered historic district,” Thomson asserts. “It's too big.” The current zoning, he maintains, would allow at least 11 housing units on the site, which he argues is plenty.

Yet the Princess Anne has 16 units; the much newer Asheville Arms complex across the street has 57.

Matters came to a head at the Planning and Zoning Commission’s May 1 meeting. The commission must sign off on the rezoning in order for it to proceed to City Council. If the petition drive is successful, a supermajority (five votes) will be needed to gain approval.

Faced with neighborhood resistance, PBCL asked for a postponement so it could retool the design in response to those concerns. P&Z is now slated to consider the rezoning July 18.

A place to lay your head

“There's one constituency that gets left out of these conversations a lot: the Asheville residents that desperately need affordable housing,” says local activist Lindsey Simerly, who chairs the city's Affordable Housing Advisory Committee. “You have people that commute from Haywood, even Swain County, because this is where the jobs are but they can't afford a place to live here.”

Despite having worked full time as long as she's lived in Asheville, Simerly says she’s been homeless several times, “the kind of short-term homelessness we don't talk about very much, when you can't pay your rent and hope you can crash on a friend's couch.”

It’s simple: if you work a full-time job in the city of Asheville, you should be able to live here. We have a moral obligation to make that happen.

Lindsey Simerly, chair, Affordable Housing Advisory Committee

She’s well aware of the intense demand for housing in the city, which sends the 2025 Plan’s twin goals of increasing density around downtown and preserving existing neighborhoods into head-on collision. According to the city's own projections, Asheville needs 500 new affordable housing units per year to even begin to tackle the problem.

The city analysis also notes that housing costs in Asheville, across all categories, are "higher than the fair market rate." Of the state's major metropolitan areas, only Raleigh-Durham has a higher average rent; Asheville, however, ranks among the lowest median incomes.

And despite its downtown core, Asheville is also a relatively low-density city: 18th in the state, despite having the 10th largest population.

“The only way for us to deal with that is to build more densely,” says Simerly, who ran for City Council in 2007 and served on Rep. Heath Shuler’s staff. While some of that new construction can be in “prime locations” like South Slope and the River District, she continues, “Our other neighborhoods will also need to become more dense.”

Meanwhile, according to the N.C. Employment Security Commission, 37,000 of Buncombe County's roughly 115,000 workers earn less than $25,000 a year. Nearly half of Asheville’s rental households (7,957 out of 16,700 total) pay more than 30 percent of their income in rent, census data show. Labeled “cost-burdened households” by the census, their rent eats up so much of their income that they have trouble meeting other needs.

And if PBCL scales back its project’s density, notes Fort, the affordable-housing component will have to go.

Yet too often, argues Simerly, the concerns of “vocal minorities” overshadow the very real needs of people desperately seeking a place to live. For her, the 2010 fight over Mountain Housing Opportunities’ Larchmont development on Merrimon Avenue, which Thomson feels isn’t a good fit with its neighborhood, epitomizes the conflict.

“MHO got over 2,000 phone calls from people interested in those 60 units while they were building the project,” she reports. “We have to take their voices into account as well, rather than the 10 or 11 people that get upset whenever we talk about building apartments.”

For-profit developers, she asserts, “are scared to bring projects forward, because they've seen what happens to [nonprofit] developers like MHO.”

The city needs clear rules governing development and “open, honest dialogue” with neighborhoods about their concerns, says Simerly. In practice, however, the process favors bigger companies that can afford the resulting delays and design changes, she maintains.

“If you talk to most regular people on the street, I'd be willing to bet they value everyone being able to feed their kids and have a safe, affordable home within the city of Asheville over some of the concerns the neighborhood groups have expressed,” Simerly observes.

A smile with a missing tooth

For Thomson, too, the battle goes beyond this particular vacant lot and historic home. To him, it represents a whole new direction for the Preservation Society: trying to derail a push for what he feels is excessive density in neighborhoods around downtown, rather than focusing only on saving individual properties.

“This is not just about landmarks: It's about the entire fabric of a historic neighborhood,” Thomson explains. Districts like Chestnut Hill, he maintains, are “fragile,” and any development there “has to be done sensitively.”

“Look, we want something there: Right now it's like a smile with a missing tooth. We just don't want the new tooth to be gold-plated with a diamond in the middle of it, and the size be so jarring.”

Ironically, Thomson also cites the 2025 Plan: specifically, its call for the “protection, preservation and enhancement of existing neighborhoods.” In his view, that means new development must avoid any “overwhelming change” to what's already there.

Those historical and aesthetic concerns may be harder to quantify than things like housing costs and units per acre, but Thomson believes they're essential to the quality of life that makes neighborhoods attractive to begin with.

Developers, he argues, “need to find sites that offer the opportunity for density without having that jarring effect,” such as the River Arts District and South Slope. Asked to name projects that fit with their historic neighborhood, he mentions Mountain Housing Opportunities' Glen Rock redevelopment.

The East Chestnut project, says Thomson, is testing the neighborhood’s ability to rally against projects that may be inappropriate. “We'd like to do more of this, especially in inner-ring neighborhoods that face the most development pressure.”

No easy answers

Two passionately held positions, two legitimate concerns — and a city whose very popularity is increasingly forcing tough decisions.

“Growth for growth's sake is the ideology of a cancer cell,” Thomson declares. “If the only reason to grow is because we think it has to happen, then we're not looking at the full equation, especially when it comes to the historic and traditional neighborhoods that encircle downtown.”

Simerly, meanwhile, says: “There's a joke among the renter class in Asheville that you start searching for a place to live on Craigslist and an hour later, you're slumped over in your chair. It's depressing.” For her, “It's simple: If you work a full-time job in the city of Asheville, you should be able to live here. We have a moral obligation to make that happen.”

But balancing the city’s competing development goals “is very difficult,” says Planning Director Judy Daniel. “It is one of the most complex jobs we have to do.”

In the case of the Chestnut Street project, Daniel says staff gave it their recommendation because, “While there have been neighborhood concerns, there’s been such strong support [from Council] for the goals of infill and building with more density closer to major thoroughfares.”

And on the other end of the development pipeline, Fort, the architect, says: “In the end, I think our project will be better for the feedback from city staff and from the neighborhood. But here, as in every neighborhood, some people just won't like change, whatever form it takes.”

— David Forbes can be reached at 251-1333, ext. 137, or at dforbes@mountainx.com.

The reporter states that PBCL is “a local sustainable-development company.” Is this the same PBCL that recently merged with Clark Nexsen?

“We are pleased to announce that the architectural firm, Pearce Brinkley Cease + Lee (PBC+L), of Raleigh and Asheville, NC, has merged with Clark Nexsen, an architecture and engineering firm headquartered in Norfolk, VA, with branch offices in Roanoke and Richmond, VA; Charlotte and Raleigh, NC; Washington, DC; and Atlanta, Macon, and Brunswick, GA.”

FYI – This is a big renter neighborhood already. More of the homes in the immediate area are rentals rather than owner-occupied and many of those homes are broken down into multiple units. There are also a handful of apartment buildings as well. It’s definitely a mixed-age, mixed-income neighborhood.

I think a lot of the issue is “maxing out” these already dense neighborhoods with more than the infrastructure can handle – parking for example, the apartments in older homes means that most folks have to park on the streets and battle guests from the Princess Anne for spots.

Also, the original design was apparently quite contemporary and didn’t provide for much interaction with the neighborhood (no front porch and very little front yard) so it just seemed like an intrusion into this historic neighborhood. All of the other apartments mesh better, visually, and as a result, mesh seamlessly socially and otherwise.

Classic nimby. My favs are the people who are generally supportive, but the character isn’t quite right. Really? Get over it. We need to up the density in this city, which enables better, sustainable public transportation and less costly sprawl.

I’ll thank the sustainability crowd for not trashing a historic neighborhood.

Sustainability is not about new development. Limiting growth and particularly population growth is the key to finding a better balance with the environment.

True, but zoning actually harms population policy by diverting management funds away from municipal contraception. The connection to population growth is valid but zoning actually causes population growth, not allieviates it.

Municipal contraception? Does that mean Norplant becomes the US Cellular Norplant and the City pockets a million bucks or what?

“This is a big renter neighborhood already. More of the homes in the immediate area are rentals rather than owner-occupied and many of those homes are broken down into multiple units.”

Yes, but they’re often rented by private local landlords who scooped up a property or two when it was cheap and now charge four-figure monthly rates.

Now, I’m somewhat sympathetic to the argument that if you put the money down, you deserve some reward, but the “fragile community” argument is NIMBY bunk. And yes, call Dr Freud to talk about that “missing tooth” analogy.

Great article. Lindsey Simerly’s point about a vocal few is important. When former planning commissioner Jerome Jones used to vote he would acknowledge that his appointment and job as a planning commissioner required him to vote for the greater good of our community, not the vocal minority, no matter what their position or class. Those who are lucky enough to buy homes should realize that every time they walk into a store, are waited on in a fancy restaurant, or pick up dry cleaning they are being helped by a person in need of an affordable home which is most likely to. be an apartment.

Why does everyone pull the race card? Or the NIMBY card? Or the affordable housing card? If the maximum rent on the renovated units is $661, that’s not terribly affordable. I can’t even afford $661 and I make $40,000/year. That’s what debt brings you.

As someone who is very preservation minded, this is TRULY an issue of being a good fit architecturally. Listing on the National Register as a district requires that a neighborhood maintain it’s architectural integrity and its sense of place. From the looks of it, this neighborhood seems to have always been a mix of owners and renters, even from its inception. BUT that doesn’t mean that some ultra modern apartment buildings needs to go up there nor does it that some Disney like historical reproduction needs to be built. It means that a happy medium should be (and can be) achieved.

I’m president of the Preservation Society, and I believe our organization will be issuing a formal press release on this. But in the meantime, I must point out that this article is misleading in that it infers, based on the cover page headline, the whole proposed project is “affordable housing,” when in fact, affordable housing consists of only a small fraction of the work proposed.

The Preservation Society has no opposition, and in fact, supports the affordable housing component of the Chestnut Street project. That component is the renovation of an existing building for four one-bedroom units of affordable housing. In other words, they’re offering to build housing for 4 poor people. Four.

What we oppose is “spot zoning” that would allow the proposed massive structure to be built right up to the property line, with no set back, and that will contain sixteen two-bedroom condos that will likely be priced so as to be affordable only as second homes for rich people who live elsewhere.

We are opposed not to more affordable housing in the neighborhood, but rather to a building for rich people to vacation in the neighborhood.

The developer here is holding the affordable housing component hostage, saying that it won’t fix up the existing historic structure for poor people unless the City lets them build whatever the developer wants for its rich clients on the vacant lot.

I’m disappointed with how the Xpress has played right along with the developer’s script, but I guess it makes for a better story to pit one group of concerned citizens against another. I hope that future reporting on this issue will be more thorough.

Why did the Xpress talk to Jack Thomson and not you?

If these rich summer folks are unable to buy new apartments, they will outbid working folks for the existing ones. ONLY by building new places for the middle class will they be prevented from displacing the working class for older units. Also, if the neighborhood is sufficiently crowded, the rich won’t want to buy in and the place will become affordable by limited demand. New development creates affordability in nearby, existing units because affordability is the opposite of value.

The developers quite shrewdly played the “affordable housing” and “sustainable” cards, and looks like folks with quick triggers got suckered.

The existing building is proposed to be renovated to small, thus affordable, living units. Great, go for it! Makes sense, just basic developer rehab 101.

However, the empty lot on Chestnut st is proposed to see a new car-culture, drive & park under- zip up to your big screen TV in your condo, common in Los Angeles, and other car-centric cultures. This clunky elevated structure is proposed to poke much closer to the street than the neighbors, has no relationship to front yard and sidewalks, and actually discourages walking, biking, gardening, etc.. They wish to replace the current zoning, and the density it allows, with different zoning, that simply allows them to cram more units onto the site. If our current zoning does not allow the appropriate density, then lets revise it, if that is what we all want. To void a rules in place, just because someone wants to fit more cars and more units onto a site, for more profit, sets a pretty bad precedent, and does not meet the requirements for a variance (a hardship must be cited). The developer threatens that they will instead charge more rent for the “affordable” units (above an arbitrary $$) if they don’t get their rezoning. Sounds like blackmail, and well intentioned folks are being played.

This is not an affordable housing project. They are renovating an old building to include 4 small (thus affordable) apartments (yay-full steam ahead!!), but primarily want to cram more market rate condo’s on the vacant lot on Chestnut st than the zoning allows. The proposed building (think of a modern version of the Days Inn Charleston) pokes much closer to the street than the neighbors, and is all about parking your car under your condo. These types of buildings are pretty common in Los Angeles, and other car-culture cities. You are being suckered if you fall for the affordable/sustainable cards they so deftly played.

I think Mountain Xpress might take a mulligan and try again with this article, as original rendition doesn’t qualify as responsible journalism. Xpress used to be a much better paper.