Much has been written about Asheville's shortage of affordable housing, and lately, the problem has even begun attracting national attention.

A March 5 Yahoo Finance article, drawing on data gathered by the analysis firm RealtyTrac, spotlighted Asheville as one of the least affordable areas in the country, based on the gap between housing costs and income, and on how quickly those costs are increasing.

Meanwhile, city government is pushing to increase Asheville’s supply of affordable housing. Late last year, city staff commissioned Mai Nguyen, a professor at UNC-Chapel Hill, to compare Asheville’s efforts to provide more affordable housing with what other, similar municipalities have done.

Nguyen has written extensively on inequality and housing issues across the country. Her “scorecard,” completed in late January (read it here: http://avl.mx/05k), pulls together data from many prior studies. It’s also the first local report by an outside expert comparing Asheville's situation with similar problems and attempted solutions elsewhere in the state and region.

Nguyen recently spoke with Xpress about her findings.

Why are Asheville's housing costs so high?

“Income is a big part of it, because in Asheville you have a lot of homeowners that are buying up second homes or retirement homes, and that's pushing up the cost of housing,” she says. “You have a combination of prices being driven up, and the terrain in Asheville is difficult to develop on.

“As prices go up and salaries stay stagnant, or they're low-wage salaries, those combine to affect the affordability.”

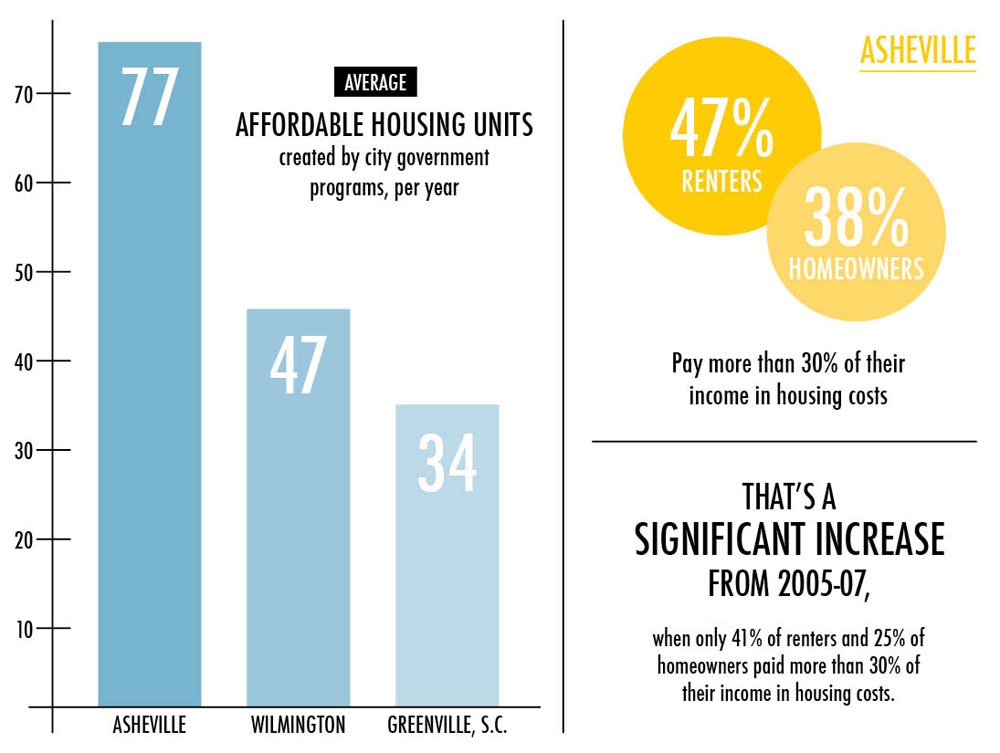

According to Nguyen's report, 47 percent of Asheville renters and 38 percent of homeowners are “cost-burdened.”

What is “cost-burdened,” and why does it matter?

Cost-burdened households spend at least 30 percent of their income on housing, defined as rent plus utilities, or mortgage plus utilities, taxes, insurance and any other associated costs. Governments typically use this figure as a measuring stick: If a large percentage of residents are exceeding that threshold just to keep a roof over their head, the area isn't considered affordable.

And high housing costs, notes Nguyen, don’t just affect individual households: They can endanger the whole local economy.

“People are spending less money on other things [because] they have less disposable income,” she explains. “As we know, we live in an economy that thrives on people having extra money to spend on goods and services. It has a ripple effect.”

The problem fuels other issues too, says Nguyen.

“When you have people working in the central city but living farther and farther out, you have increasing congestion, pollution, sprawl. That has its own set of costs to the environment and the livability of a place.”

The number of cost-burdened Ashevilleans has increased substantially since 2007, when only 25 percent of homeowners and 41 percent of tenants here fell into that category. Nonetheless, the percentage of cost-burdened renters here is still much lower than in Chapel Hill and Wilmington, where that figure tops 57 percent.

“I was actually quite shocked at the numbers,” says Nguyen, noting that Asheville “is actually a little lower than the state average” of 47.9 percent. “Roughly 50 percent of all these urban centers being cost-burdened is not a good thing for a state.”

Homeowners, however, are a different story: Only Wilmington has a higher percentage of cost-burdened homeowners than Asheville. Nguyen also stresses that the real impact of those numbers falls heavily on lower-income service workers.

“If you're making $200,000 and you're paying a third of that on your home, you probably still have some money to put into the local economy,” she explains. “Not so much if you're making $12,000.”

That, she continues, leaves Asheville's population more hard-pressed than residents of cities whose economies rely less on tourism. “I think the city is well aware that what they have now — predominantly a labor force that works in the tourism industry or the service industry — is probably not sustainable.”

How do the city's efforts to address the problem stack up?

“When they asked me to do this, I thought they were going to come out horribly compared to other places,” she reveals.

Instead, however, Nguyen’s research shows the city doing relatively well. After consulting with city staff and drawing on her own knowledge, she decided to compare Asheville to Greenville, S.C.; Chapel Hill; Durham and Wilmington.

Over the last five years, Asheville’s local government programs and partnerships created an average of 77 affordable housing units per year within the city limits. Greenville's average was 34; Wilmington's was 47.

City government, says Nguyen, has done “quite a good job. They've invested in it financially; they've supported it through collaborating with other nongovernmental entities. I think it's clear from the studies that have been done that they're really committed to supporting affordable housing. That's not true of many other places.”

Who's responsible for those efforts?

The city’s Housing Trust Fund and nonprofits such as Mountain Housing Opportunities have helped, and Nguyen says the trust fund, in particular, is unusual: Most cities rely on state and federal grants to support affordable housing, rather than taking money out of their general fund.

But her report also credits the Asheville Regional Housing Consortium, which distributes funding from multiple sources and creates hundreds of affordable units per year across Western North Carolina. The consortium, a combined effort by governments at all levels, outperformed similar entities in larger areas, Nguyen found. Last year, for example, Durham's consortium helped create 167 affordable units, compared with 401 for the Asheville group.

What should Asheville do?

Nguyen's report advises the city to follow Chapel Hill’s and Greenville’s lead in establishing and funding a land trust that could buy property in key areas and guarantee that it will be used to develop affordable housing.

At present, notes Nguyen, Asheville guarantees that its affordable units will remain so for only a set period of time.

“At some point, that affordability will sunset, and then Asheville will have to go through the process of creating more affordable housing,” she points out. “For the long term, they really need to consider permanent affordable housing.”

At the same time, she cautions, “They also need to think through how to … integrate different types of housing and different levels of income in a neighborhood, so you don't have concentrated poverty.”

In addition, the report recommends dedicating a specific revenue stream for affordable housing. Durham, for example, designates a portion of property tax revenues.

Are we doing enough?

Is demand still outstripping supply, despite Asheville’s efforts? Nguyen calls it “an interesting question” that, though beyond the scope of her score card, is one city leaders need to consider.

“Thinking about the population that will live there in the future is really important for Asheville,” she says. “It's a combination of figuring out what the jobs are going to be and the city working to diversify the economy, so they have people who can afford the housing.”

— David Forbes can be reached at 251-1333, ext. 137, or at dforbes@mountainx.com.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.