Like a good walk through the wilderness, DuPont Forest: A History doesn’t take the most straightforward route to its destination. The newest offering from Asheville-based outdoors writer and occasional Xpress contributor Danny Bernstein navigates the proverbial switchbacks through over 200 years of stories about the land that now comprises DuPont State Recreational Forest in Henderson and Transylvania counties.

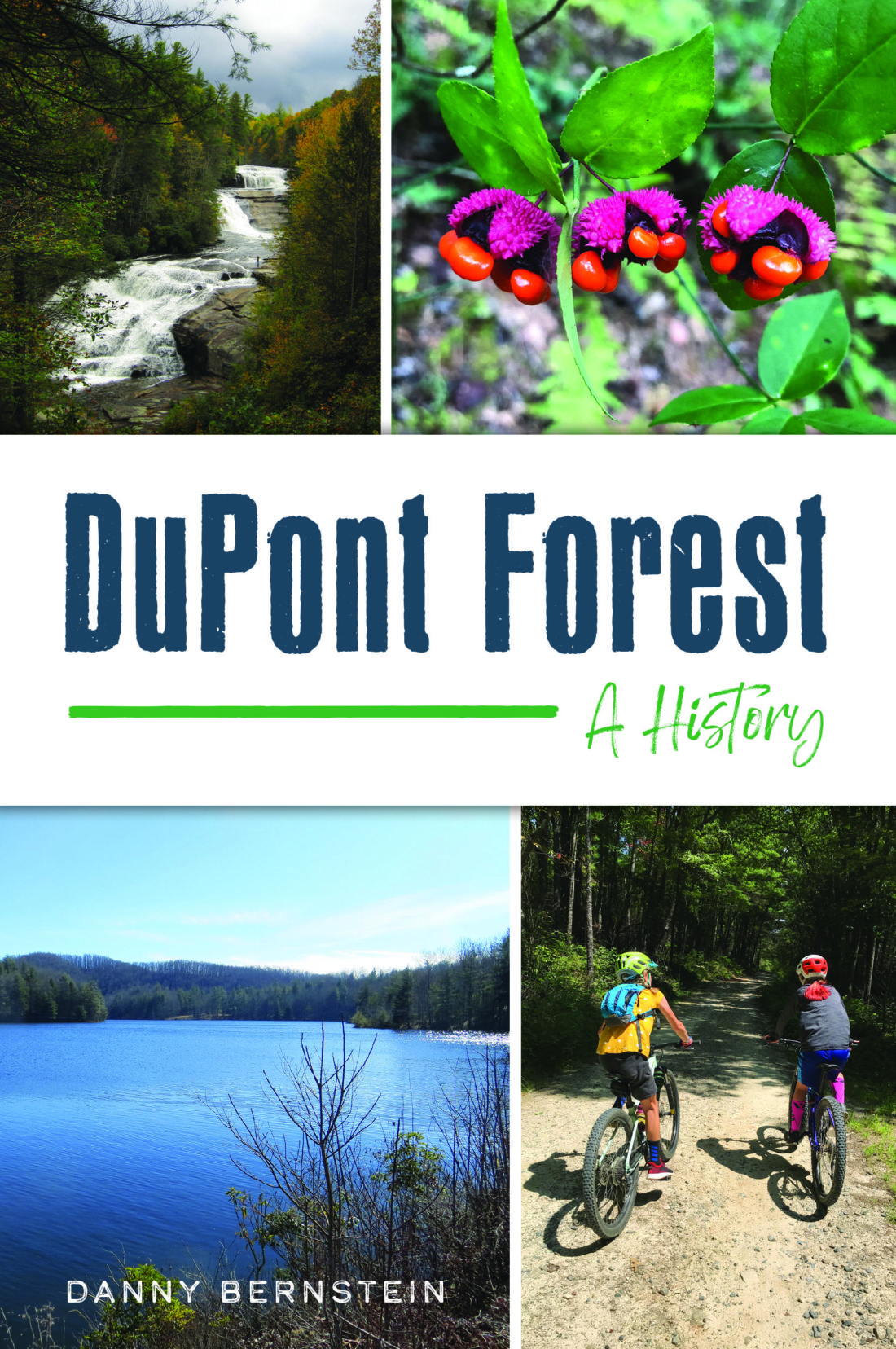

A discussion of Cherokee rock carvings is shortly followed by a guided tour of the forest’s three most popular waterfalls. Praise from the many mountain bikers who use its trails sits close to a mention of how The Hunger Games safely filmed Jennifer Lawrence running across Triple Falls. Archival photos of DuPont’s silicon manufacturing plant, which once dominated the property, rub shoulders with Bernstein’s own shots of modern-day hikers.

Where the book arrives, Bernstein says, is an appreciation of how the forest’s history remains accessible to the present. “In Pisgah [National Forest] or the Smokies, it’s very difficult to know exactly who owned the land before it became public. With DuPont, it’s not,” she explains. “You can trace all of the land to somebody who sold it or gave it away to the state.”

Bernstein will debut DuPont Forest: A History in Asheville through a virtual event hosted by Malaprop’s Bookstore/Café on Thursday, Sept. 17. The livestreamed conversation will also feature Holly Kays, the Waynesville-based outdoors editor and news reporter for Smoky Mountain News.

Links to the past

While most previous writing on the forest (including Bernstein’s most recent Xpress article; see “Beyond the Waterfalls,” Sept. 19, 2018) has highlighted what she calls “the drama” of preserving the land around DuPont’s waterfalls, the author wanted to take a deeper approach. Her resulting book represents the first comprehensive survey of the area’s history.

Among her most delightful interviews, Bernstein says, were Western North Carolina residents who had experienced the land’s recreational joy as children in the 1950s and ’60s, decades before the 1996 establishment of the state forest. Some had stayed at Buck Forest Lodge, a fishing and hunting club near High Falls that closed in 1956, while others had swum in the lake established as a DuPont employee recreation area.

“We’d play at High Falls all day, hiking and sliding down a tributary of the falls. After two or three trips down the falls, our jeans were ripped, but so what?” recalls Ellen McCotter, about her visits to Buck Forest Lodge as a teenager. “Maybe we got back to the lodge for a sandwich when we were hungry.”

Those conversations are supplemented with extensive archival material, drawing from both the Transylvania County Library and the Hagley Museum and Library in Wilmington, Del., which focuses on corporate history. The Brevard plant published its own magazine, Fotofax, which Bernstein says combined basics such as company policy reminders with jokes and announcements of outdoors fun.

From a representative 1960s newsletter, Bernstein quotes one witticism appropriate to the era: “No wonder today’s teenagers get mixed up. Half the adults are telling him to find himself and the other half to get lost.”

Bernstein emphasizes that the book contains no secrets about the forest or its owners, just the results of diligent research and a genuine interest sparked during hikes with former DuPont employees through the Carolina Mountain Club. “Anything that everybody told me was something that anybody could have found out, had they spent two years on their butt trying to do this,” she says with a laugh.

Hole in the story

At over 200 pages, DuPont Forest: A History feels as if it leaves few questions unanswered. Yet Bernstein says one issue is something no one can currently resolve: the fate of the “doughnut hole,” a 476-acre plot surrounding the former manufacturing plant that sits in the middle of the forest.

Although the doughnut hole is off-limits to the public, Bernstein was able to visit with Chet Meinzer, who oversees DuPont’s cleanup operations at the site. Nearly all of the buildings and chemical contaminants have been removed at this point, she reports, but government regulators still have to sign off on the work; after that, the N.C. Forest Service must develop a plan for the land, which could add years to the process. “Frankly, I don’t think I’m ever going to see it open,” she says.

Whether that last piece of the forest is reserved as a wildlife buffer or developed with trails, Bernstein adds, DuPont will continue to prove a major draw for lovers of the outdoors. She notes that she’s seen license plates from as far afield as Canada in the parking lot for the forest’s waterfalls, while national bicycling magazines have used its trails to test new equipment.

The forest’s past may be rooted in WNC, but its future will be part of a broader picture. “It is no longer a local forest,” Bernstein says. “I don’t know if that’s good or bad, but it ain’t.”

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.