Samantha Brawley thought she had tried everything to curb her opioid addiction.

She had visited addiction treatment centers and attended Alcoholics and Narcotics Anonymous meetings. Each time, she gained new tools to help manage her illness. And each time, she still had cravings, leading her back to drug use.

Then someone suggested that Brawley try MAT, or medication-assisted treatment. Her family and friends didn’t support her decision to start the treatment, but for the first time, she felt as if she had a shot at a better life.

That was five years ago. Brawley, still on MAT, now works as a MAT peer support specialist at the Buncombe County Detention Facility, helping individuals in custody treat their addictions and safely reenter the community. Once formerly incarcerated at the same jail, Brawley sees her job — and the county’s MAT program, nearing its one-year anniversary of expanded resources for inmates — as a way to ensure no one else goes through what she experienced.

“I know what I needed when I was in jail and didn’t get it, because at the time it wasn’t available,” Brawley says. “When I made the choice to start MAT, no one supported me. I don’t want that to be the case for our participants. I want them to know it can be their first option, and their only option.”

More to give

Medications such as buprenorphine and naltrexone can help normalize the brain chemistry of people with substance use disorder, relieving psychological cravings and blocking the euphoric effects of opioids and alcohol without dangerous side effects. In many cases, MAT increases retention rates for people in therapy while decreasing illicit drug use and mortality rates, says Dr. Tracy Goen, an addiction specialist and medical director at the detention center.

The Buncombe jail used MAT to treat pregnant women for years, says Sarah Gayton, the Sheriff Office’s community integration and MAT services director. But it wasn’t until 2019, when the county received a $283,000 grant from the N.C. Department of Health and Human Services, that the program started opening to a broader population.

That July, staff began collecting data during the jail’s intake process to better understand the type of services needed, Gayton explains. In March 2020, the team began offering MAT to anyone entering the facility who was already on medication, and new patients began enrolling in the program in August.

All new inmates are screened at intake for opioid use disorder, says Felicia Wood, a registered nurse working with the MAT program. For anyone indicating opioid use disorder, the jail’s harm reduction team gives a brief introduction to the program; eligible detainees, generally those being held at the jail for at least two weeks, can opt into treatment at any point during their stay.

The team has provided education materials and case management for over 1,000 individuals since receiving the initial 2019 grant, Gayton says. Since last March, she estimates 20-30 people have begun MAT and another 120 have been able to continue treatment while detained.

Beyond detention

As Gayton and her team were establishing their MAT program, they worked with the Buncombe County Department of Health and Human Services and the Register of Deeds to learn more about patterns in county overdoses. They found that roughly 50% of Buncombe County residents who died from an opioid overdose between 2010 and 2019 passed through the detention center at some point in their lives. Of those who visited the jail, 50% had been detained for fewer than 24 hours.

“Once we figured out that half of the people who came through the facility and died would only be here for a day, we made the decision to frontload a lot of our programs to provide the most service in the shortest amount of time,” she explains.

Everyone identifying as an opioid user at intake is given an overdose kit containing community resources and naloxone, an overdose reversal drug, upon release from the jail. Reentry services are also available to individuals with opioid use disorder through the health department and Asheville-based nonprofit Sunrise Community for Recovery and Wellness’ Linkage-2-Care program, adds Amy Upham, Buncombe County’s opioid response coordinator.

The partnership pairs individuals with recovery programs, harm reduction services and basic necessities, like a place to live and personal hygiene products, after their release. Other county harm reduction strategies include syringe exchange programs and naloxone distribution and training.

Population shifts

The MAT program’s expansion came as county leaders were also making a concerted effort to reduce the number of people housed at the detention center to limit the spread of COVID-19. In 2020, following the release of more than 200 detainees at the start of the pandemic, the average daily jail population was just under 400, down from 533 in 2019.

With the end of the pandemic in sight, Buncombe County Sheriff Quentin Miller says it’s time to put the MAT program “in four-wheel drive. We have the potential to serve more people with the numbers changing, which is a good thing. But at the same time, it gives us the opportunity to really develop this out.”

Simultaneously, Buncombe County is working to permanently reduce the jail’s population through its ongoing Safety and Justice Challenge. The county Board of Commissioners voted Feb. 16 to accept an additional $1.75 million grant from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation to divert people away from the jail and into behavioral health and substance abuse treatment programs. The grant also calls for an equity consultant to reduce racial disparities in sentencing.

The MAT program was designed to “fit into the natural jail crossroads,” Gayton says, regardless of how many inmates the facility houses. If the population were to suddenly jump or drop, protocols would remain the same: Everyone will still be screened at intake, and as individuals in custody move through the jail’s existing medical timeline, MAT will continue to be offered at every step.

When people on MAT are released back to the community or sent to a different facility, the team usually sends them with five days worth of medication, enough to tide them over until they can find another treatment provider. But fewer than 1% of the more than 5,000 U.S. jails and prisons offer MAT to people in custody — and only 11 of North Carolina’s jails currently offer the medication. Those who are transferred to a facility that doesn’t offer the medication are likely out of luck.

“We’ll put them in line for continuation, but if the facility doesn’t offer it, they don’t get it,” Gayton says. “We try to send them with a few doses of MAT to take when they get out, so they’ll have that lifesaving safety net, and they’ll have their overdose kit. But unfortunately that’s about all we can do.”

‘A beautiful reset’

A year after the MAT program’s expansion, its leaders are beginning to notice positive effects rippling through the community. It’s not uncommon for participants to break down in tears as they grasp what a MAT regime might allow them to accomplish, Gayton says, and a number of individuals in custody who rejected the program at intake are changing their minds and seeking treatment weeks or months after arriving at the jail.

Kevin Rumley, the coordinator for Buncombe County’s Veteran Treatment Court, has only heard positive things from his clients, many of whom have spent short stretches of time at the detention center. Now, a brief stint in jail means his clients already on MAT will be able to continue their treatment without any issues. For others who may have fallen off the MAT wagon, Rumley says the jail provides a “beautiful reset” to resume treatment.

“Jail is no longer the place where you go and are forced to detox off of your prescribed medications, but it’s a place where you can continue your recovery,” Rumley says. “It’s kind of a paradigm shift. Jail used to be punitive but now there’s this treatment focus.”

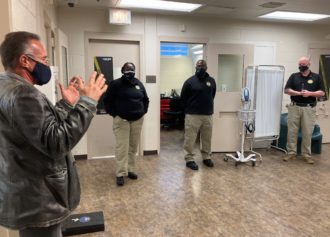

Detention center officers who were skeptical of the program at first have also come to appreciate MAT as they’ve learned more, Brawley notes. Wood, the jail’s MAT nurse, says she now gets referrals from officers about inmates they believe could benefit from the program. “Having positive people in the building who understand how it works is so important,” Wood says. “Their enthusiasm is infectious.”

“Buncombe County has started working on the solution instead of the problem,” Brawley adds. “We overcome barriers that, being a person formerly incarcerated, I’ve never seen done anywhere else.”

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.