Award-winning poet and Burnsville resident Pat Riviere-Seel remembers catching the poetry bug her sophomore year of college at N.C. State University. “I realized that I had no choice but to write poetry,” she says.

Among those whom she credits for revealing the power of the form is fellow North Carolina poet Thomas Heffernan, who taught one of Riviere-Seel’s senior English literature courses.

Poetry, however, took a back seat as Riviere-Seel pursued a career in journalism and later a stint as a lobbyist for nonprofit organizations in the Maryland State House. Eventually, she returned to her home state, earning a Master of Fine Arts from Queens University of Charlotte.

Though she’s won multiple writing awards, she says her greatest accomplishment as a poet “is my role as a ‘poetry midwife,’ a teacher, who encourages and helps other poets become the best poets that they can be.”

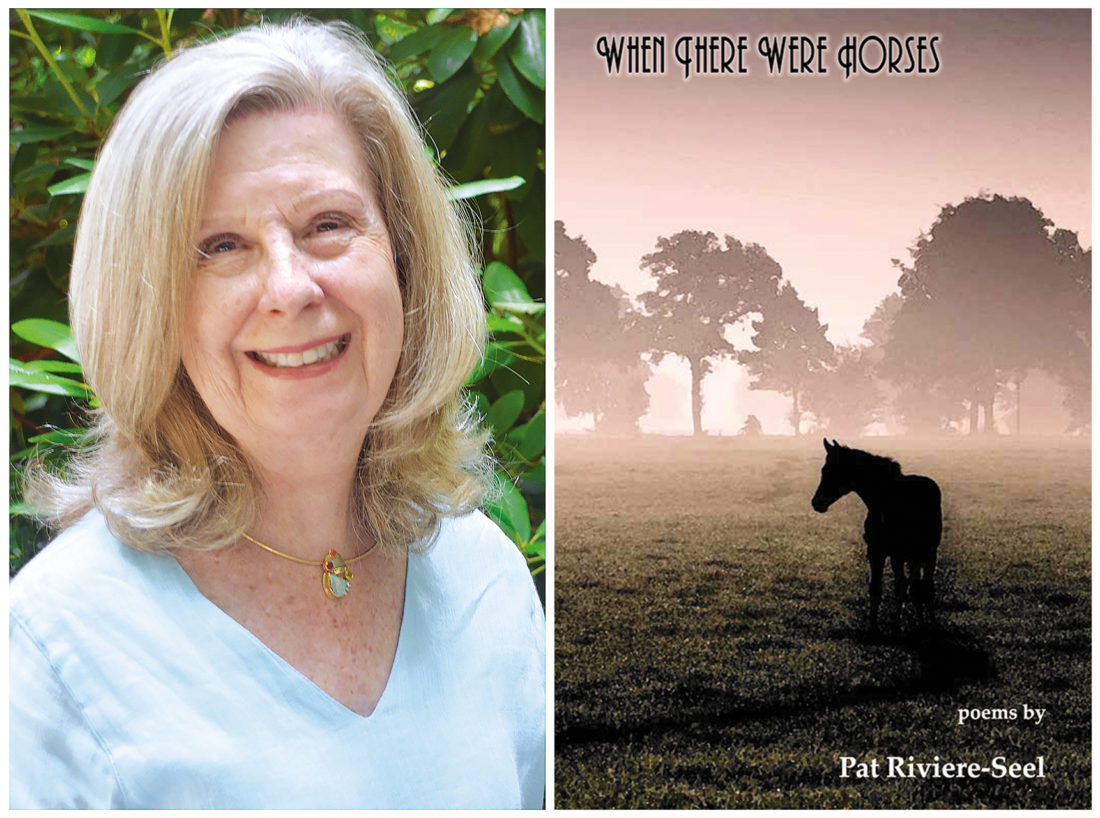

Riviere-Seel recently shared her poem “Reclamation” from her 2021 collection, When There Were Horses. Along with the work, the poet speaks with Xpress about her writing life.

Reclamation

First she reclaims the garden,

tangled north facing plot

where summer comes slow.The root cellar holds cloudy jars

neatly stacked on wooden shelves.A neighbor bush-hogs the brambles,

the wild blackberries, the weeds

grown tangled from neglect.A storage shed keeps stories of better

days wrapped in cobwebs and dust.An artist whose medium is dirt walks

behind his Gravely tractor turning soil

while she follows raking, breaking clods of clay.Together they carve a spiral and dig

keyholes for herbs. The man plows long rows.Autumn she plants buckwheat, begins

a compost pile. Winter she curls into the sofa,

reads seed catalogues and stokes the fire.Spring brings blueberry bushes, flats of basil.

She plants by the moon and dreams of chickens.A tree trimmer prunes the apple tree’s branches

split by winter winds and ice. Order brings its own

regrets, but she cannot resist the impulse.Sunrise she kneels between the rows pulling weeds

from soil still damp with dew, thinks to stay awhile.

Xpress: There are so many wonderful details in this poem. Is there a particular line that got the piece going?

Pat Riviere-Seel: Like many of my poems, this one began with an image — the large garden that I created when I bought a little house in the woods of Yancey County in 1993. The year prior, I had moved from Annapolis, Md., back to North Carolina, to be closer to my dad and my extended family in Shelby. I had dreamed of retiring to the North Carolina mountains, a favorite place since my childhood. But, I made the move sooner than anticipated when I accepted the job as editor of a bimonthly journal, which I renamed Voices, published by Rural Southern Voice for Peace.

When my dad died unexpectedly in March 1993, I realized that for the first time in my life I was completely alone, with no immediate family — no parents, no siblings, no children, no significant other or partner. I decided to buy the house in Yancey County in part because it offered the chance to create a garden. I did not know at the time how long I would stay, but I wanted something to literally sink my hands into. I lived there for five years, and the garden became my joy and solace. But I did not begin the poem until more than 25 years later.

Given the personal inspiration behind the piece, do you find that readers sometimes have a hard time distinguishing the poem from the poet — especially as many of your works are written in the first person but are not necessarily written about your personal experiences?

How to make that connection with the reader without the reader assuming that the speaker is the poet? It gets tricky, especially when writing poems that evoke strong emotions. For example, a friend read a poem where the speaker in the piece talked about the death of her brother. My friend did not have a brother. After the reading, several people came up to her and expressed their condolences. She was mortified. It was a poem. The speaker was not the writer.

That story has stayed with me for years and presented a question I cannot answer very well: What would I have done? My friend did not tell the reader that she did not have a brother, but she wondered afterward if she should have. If she had said that was not her experience, would the reader have trusted the speaker in her other poems? Does it matter?

We can never control how any reader reacts to our poems. Unless the poem is obviously a persona poem, there is always the risk that the reader will identify the poet as the speaker in the poem, believe that the experience belongs to the speaker. So, I try not to think about that too much.

The poet’s job is to craft a work of art. Sometimes that comes from personal experience. More often, I believe, the poem comes from wanting to explore an image, a line, a situation or an experience. It’s that exploration, along with imagination, that goes into creating the poems.

The details in this poem and others in the collection are so specific and layered. I wonder if this is a talent you’ve always had or one that you’ve cultivated over the years. If the latter, in what ways did your understanding of poetry evolve and reshape the way you perceive and write about the world around you?

I like to think that the images in my poems have come from the skills that I’ve developed — and am still developing — as I work on my craft. I don’t think that I have any innate talent for images or poetry. I fell in love with poetry when I first read William Blake in high school. His images were so powerful, so vivid, otherworldly. And yet they allowed me to see a very concrete world that existed in imagination. The connection to the images was at first very visceral.

As I began to study poems and poetry, I started asking, how did the poet do that? Why that particular image? What does it allow me to see that I did not see before I read this poem? I also began asking the question we all ask as we begin working with metaphor: What’s it like? If I begin a poem with an object, I investigate the object — what draws me to that particular object and why? Where is the beauty? Where are the flaws? And always, what’s it like?

As I frequently told my poetry students, there are two things that are unique to each poet, something I cannot teach anyone: No. 1: Your ear for music. No. 2: The way you see the world.

Lastly, who are the four poets on your personal Mount Rushmore?

Walt Whitman, Emily Dickinson, Elizabeth Bishop and Marianne Moore.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.